If I were to offer up the opinion that Francis Ford Coppola is one of the great American filmmakers, I suspect that few people would object too strenuously to such an assertion. Likewise, if I were to say that his run of films during the 1970s—a period that saw him put out “The Godfather,” “The Conversation,” “The Godfather Part II” and “Apocalypse Now” one after the other—is one of the most astounding sustained peaks of accomplishment achieved by any artist, I am willing to be that most people would go along with that as well. However, if I were to say that of all his cinematic efforts, the one that I love the most—the one that never fails to thrill, awe and astonish me every time that I see it—is actually his notorious and financially ruinous 1981 musical extravaganza “One from the Heart,” my guess is that most people would assume that I was either joking or being deliberately perverse in the name of provocation.

And yet, as much as I love and admire so many of the films that he has made over the years, from those aforementioned stone-cold classics to such equally impressive accomplishments as “Rumble Fish,” “The Cotton Club” and “Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” it is this one that stirs and dazzles me the most and reminds me of why I fell in love with the movies in the first place. Now, more than 40 years since its disastrous original release and over 20 since the first time that Coppola, as he has tended to do with his work throughout his career, has reworked and reissued it, he has done it again with “One from the Heart: Reprise,” a 4K digital restoration of the film that sees him further refining the material into a version roughly 14 minutes shorter than its original release. This new edition is now being released in theaters in advance of its eventual appearance as a 4K UHD and, speaking as an unabashed fan of the film, the chance to once again see it on the big screen in all its glory and, hopefully, expose a new audience to its wonders without any of the background Sturm und Drang that accompanied its original release, will hopefully go down as one of the key cinematic events of the still-young year.

The story of what happened has been chronicled in many places—most recently in Sam Wasson’s The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story—so I will be brief in recapping it here. Having survived the major artistic gamble of “Apocalypse Now,” Coppola decided to double down by purchasing his own Hollywood studio, dubbed Zoetrope Studios, to serve as an artistic laboratory where a wide array of talents, both legendary and emerging, could work with the latest advances in filmmaking technology. One of the keys to this would be the use of what he dubbed “electronic cinema”—a process involving the use of computerized “pre-visualizations” to plan how scenes would look in advance, video cameras on the set that would allow filmmakers to immediately see how things looked and editing by computer that would allow for greater freedom in terms of putting the elements together. These notions would eventually become industry standards but Coppola was the first to employ them on such a grand scale and the start-up costs proved to be high and would soon spiral out of control.

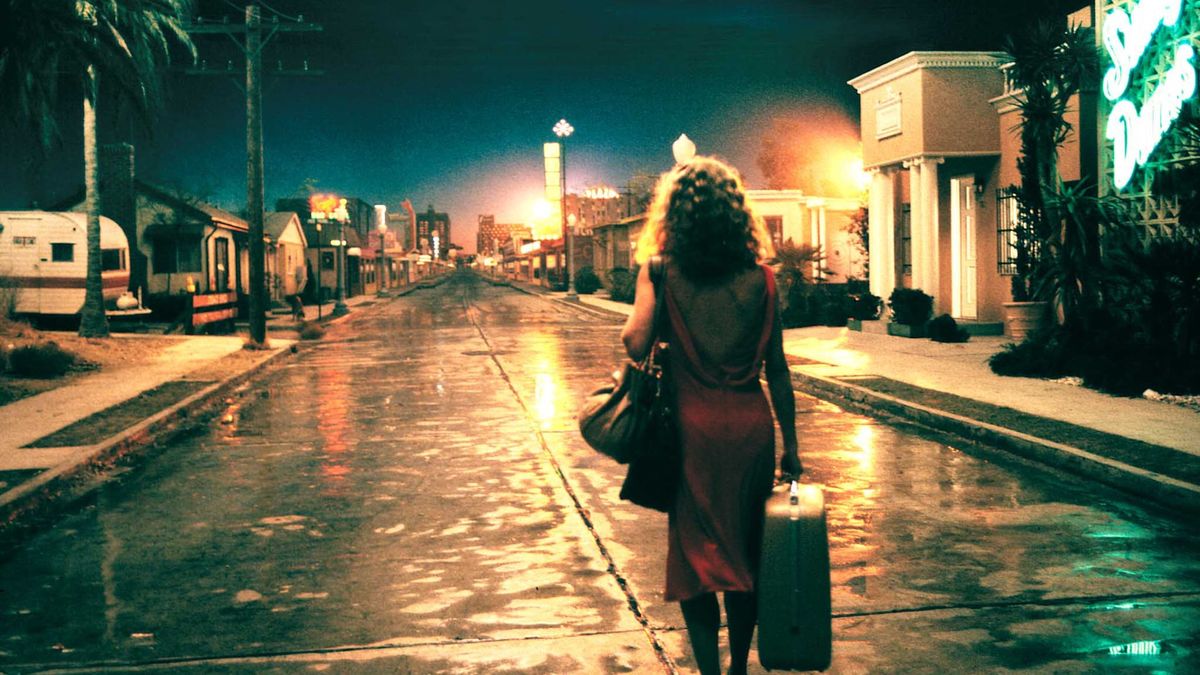

Instead of doing the film as the straightforward Chicago-set romantic drama indicated in the original script by Armyan Bernstein, Coppola rewrote it and set it in that most dreamlike of American cities, Las Vegas. However, befitting a story that he was now seeing as a tale of dreamers contemplating taking a chance on a destiny that could prove to be as illusory as “spit on a griddle,” as one character succinctly puts it, he decided that instead of shooting in the actual Vegas, he and production designer Dean Tavoularis would recreate it on the Zoetrope stages in order to help achieve the ultra-flashy look that he was hoping to achieve. By this time, he had also decided to make the film as a musical and while he would go as far as to hire the legendary Gene Kelly to serve as a consultant for the film’s major dance scene, Coppola’s approach was far removed from the norm—instead of the actors belting out the tunes, Tom Waits (who had been hired to compose the songs) and Crystal Gayle would sing in the background as a way of commenting on the action in a conceit closer to MTV than MGM. To accomplish all of this required lots of money and, as was the case of his previous project, Coppola essentially gambled his new studio and his financial stability on the idea that viewers would spark to what he had in store for them.

For those encountering “One from the Heart” for the first time, after hearing all the legends about it, is how simple and direct the story is at its heart. Frederic Forrest and Teri Garr star as Hank and Frannie, a couple who, as the story begins, are about to celebrate their fifth anniversary as a couple on the Fourth of July. Although ostensibly happy, the two has begun to drift apart and this is apparent in their anniversary gifts for each other—Frannie, a dreamer who works as a window dresser in a travel agency, gets them two tickets for a vacation to Bora Bora while the more practical Hank, who co-owns a local junkyard, gives her the deed to the starter home where they live.

After a quarrel where they vent their frustrations with each other, they both stomp off into the night to nurse their emotional wounds with their best friends (played by Lanie Kazan and the great Harry Dean Stanton). Amidst the vibrancy of the Vegas strip, they each almost instantly find a new potential parter promising the kind of glamour and excitement that had long escaped their own relationship—Frannie is swept off her feet by Ray (Raul Julia), a suave singer who says that he actually has been to Bora Bora while Hank is instantly beguiled by sexy circus performer Leila (Nastassja Kinski). Over the course of that long night, all is blissful for Hank and Frannie and their new circumstances but the next morning, the glitzy neon is replaced by the harsh light of day and they have to decide whether to take the chance on an uncertain future or go back to the way things were with each other, assuming that they can even get back to that point anymore.

As storylines go, this is not exactly groundbreaking, I admit, and much of the derision that the film faced when it was released came from incongruity of Coppola following up his string of ambitious epics with a wispily-plotted story involving the romantic misadventures of a relatively mundane couple. Furthermore, the extremely stylized and deliberately artificial look that Coppola accomplished with the aid of Tavoularis and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro struck them as little more than a desperate attempt to distract viewers from the alleged triteness of the story and the characters. While Coppola had made an art out of dancing on the precipice of artistic failure so many times before, he was unable to save himself or his film this time around—exhibitors and distributors didn’t want to show it, most critics hated it and audiences stayed away in such droves when it finally opened in early 1982 that Coppola lost his studio and plunged into a financial abyss from which he would only emerge after a decade of work-for-hire projects.

And yet, as personally and professionally disastrous as the film might have proven to be to Coppola back in 1982, time has been exceedingly kind to “One from the Heart” over the years. For example, the go-for-baroque visual style employed by Storaro and Tavoularis was so far ahead of its time that even today, more than 40 years since its original release, it still feels utterly new and unique, a triumphant reminder of how cinema is, ultimately, a visual medium and one that is constantly hungry for the kind of stunning cinematic conceits that Coppola is constantly serving up over the course of its running time. What has become more evident is that the extreme visual style is not just simply employed to dazzle the eye but to advance the emotional through line in ways that resonate more deeply than conventional dialogue exchanges. Using the newfangled editing technology, Coppola is able to superimpose imagery in ways that make it seem as one scene involving Frannie is going on with another one in the background featuring Hank—not only is he able to seamlessly move between the two but he is able to quickly and creatively underscore just how deeply intertwined the two characters are despite their avowed dissatisfaction with each other. The effect is almost overwhelming in its sheer formal beauty and is enough to leave viewers with a taste for the flamboyant practically swooning in their seats.

However, subsequent viewings reveal that the human element is much stronger than its reputation might suggest. While it might have seemed perverse at the time to cast straightforward actors like Forrest and Garr in the leads instead of megastars who might have stood out more amidst all the glitz, it proves to be an inspired choice because their comparatively ordinary humanity serves as an effective counter to the slickness that surrounds them on a daily basis. Although they are not especially likable in their early moments together—their big argument is convincingly brutal—they grow more sympathetic over the course of their respective nocturnal adventures and by the time the film approaches its final moments, we finally see what it is that they initially saw in each other, leading to a surprisingly moving conclusion.

As the lovers who represent the kind of wild fantasy that places like Vegas are built upon, Julia and Kinski have showier, sexier roles and they are both great in them. As the suave Latin love Ray, Julia delivers a master class in suave self-assurance that is always a hoot in the way that he transforms practically any situation—whether doing a tango with Frannie or getting busted when Frannie discovers that he is actually a waiter in a tacky diner—into an opportunity for seduction. As for Kinski, her casting in what would be her first American movie is inspired—at the time, she was one of the biggest sex symbols in the world—and her sheer physical grace and beauty is enough to make you forget all the other visual treats on display whenever she is on the screen. However, her role is ultimately more than just a blatant male fantasy because when the action shifts to the morning after and she goes from fetish object to a normal person that the once-besotted Hank can no longer connect with, she is able to make the transition in ways that feel both real and heartbreaking in equal measure.

I have been in love with “One from the Heart” ever since I first saw it on VHS way back in the day and every time I come back to it, I am relieved to discover that my youthful ardor for it has never dimmed. What is interesting, however, is to see how its reputation has changed somewhat over the decades as more people have come to appreciate Coppola’s genuine accomplishments here. One can even see its influence in a number of other highly stylized and wildly ambitious works that have come out in its wake, including such films as Leos Carax’s “The Lovers on the Bridge,” Denis Villeneuve’s “Blade Runner 2049,” Damien Chazelle’s “La La Land” and most of the cinematic output of Baz Luhrmann. There are even reports that the upcoming “Joker: Folie a Deux” uses it as a key influence in the way that the first “Joker” utilized “The King of Comedy,” though hopefully more competently.

However, having written all of this, I am well aware that “One from the Heart” is ultimately never going to be the kind of film that will achieve the kind of broad public favor that Coppola was able to achieve with his landmark works—the combination of cool technical accomplishment and open-hearted emotionalism is the sort of thing that will always inspire jeers as condescension from those unable to land onto its peculiar wavelength. For those who are able to make that landing, it is the kind of film that simultaneously dazzles the eye and touches the heart in ways that, once seen, will never be forgotten. It is a cinematic feast lovingly prepared by a master chef that will always go down as one of the truly unforgettable touchstones of my moviegoing life and it is my hope that it becomes just that for you as well.