• Roger Ebert / April 7, 1996

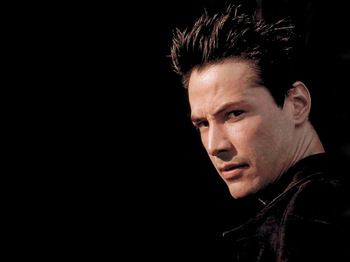

In an age when young movie stars are famous for their clothes, their homes, their cars and the clubs where they hang out, Keanu Reeves is famous for his suitcase. He’s been living out of one for nearly three years, occupying hotel rooms in the cities where his movie career takes him.

In the cold winter of 1996, it brought him to Chicago, to make a movie named “Chain Reaction.” One day in February he was inside a vast old warehouse over near Lake and Paulina, shooting a scene with Morgan Freeman, about a conspiracy to suppress a new source of low-cost energy. Reeves and Freeman are both on Hollywood’s A-list these days, and the movie is a big-budget production with heavy names attached: The producer is Richard D. Zanuck, and the director, Andy Davis, is still hot after his hit with “The Fugitive.”

Davis has shot almost all of his films in Chicago–he uses locations here better than any other filmmaker ever has–and that’s why the movie, which could be set anywhere and partly takes place in an underground bunker, was being filmed here. We were in the bunker right now, in fact, for a confrontation between Reeves, as a young man who knows of a sensational breakthrough in energy, and Freeman, as a man who heads a foundation that allegedly supports such breakthroughs but may, in fact, be a front for efforts to contain them.

The bunker set was large and sleek and glossy: Lots of glass, steel, marble, wood, suggesting a wealthy and powerful organization. We were allegedly hundreds of feet underground, somewhere near the Argonne National Laboratory. Reeves and Davis had just finished a low-key script conference at the organization’s board table, and now there was a break while the cinematographer lit the scene. Reeves was costumed in jeans and a scruffy flannel shirt, open over a T-shirt.

He has been acting for nearly 10 years, often in roles that required him to be sensitive, poetic, doomed or romantic, but it was his hard-charging action role in “Speed” that made him a box office factor, a “bankable” lead for a major production like this one.

So are you still living this peripatetic life? I asked him. Living out the legend we’ve read in the magazines, that you exist out of two suitcases in hotel rooms and don’t own a house and….

“Yes,” he said. “Sounds quite bohemian and gypsy-like, doesn’t it?”

And very simple.

“It’s getting simpler. I’m down to one bag now, and smaller rooms in hotels. Yes, I am.”

He twinkled. I think. Maybe he was serious. He was right in between somewhere.

Yeah, I said. In your business, why have a house, when you’re not home for months on end…

“Hopefully, if you’re working,” Reeves said. “Hopefully you’re working to buy a house and put furniture in it if you want to.”

Can you sort of walk around a strange city and not have people asking for your autograph?

“Sure.”

Do you have little tricks that you do?

“I don’t need them. I kinda look like a normal guy, so….”

Truman Capote, I said, walked down Fifth Avenue once with Marilyn Monroe, and she said, “Watch this.” And for one block she wasn’t Marilyn Monroe and for the next block she was and he couldn’t see what she was doing but for the first block she was totally ignored and the second block she caused a riot.

“Truman Capote was great.”

So what do you travel with? Books, a computer….

“I don’t have a computer. Books and a couple of things of clothes.”

When you finish reading a book, where does it go?

“Piles up. I have a nice little pile in my hotel room.”

But at some point you move hotel rooms and then what happens?

“They go to my sister’s house. She’s got all my books from the past year, all in different boxes. Just recently, I’m missing a lot of my belongings. I miss some of my clothes, some of my books. It was nice to have them around when I did have a house, you know. It’s nice to come home. But…”

That may be a pre-house buying feeling that you’re experiencing.

“I’ve gone looking for houses but I could not find one that I liked and could afford. The ones I like I can’t afford.”

You mentioned the word bohemian, which is a nice old word.

“Yes, it is a nice old word. Like existential.”

He smiled. Is this lifestyle, I asked, almost a way of maintaining your balance, because you’ve had transition into this weird existence of being known as a movie star?”

“I don’t really feel that movie star thing. I don’t think I……from the response that I’ve gotten workwise…”

You could choose to feel that way if you wanted to.

“I think of Morgan Freeman as a movie star, you know. My perception from the feedback that I get from the street, the feedback that I get from the people I work with, roles offered and all that sort of thing and the attention, it’s just…..you know, I’ve been lucky enough to work in some films that have, you know, been good, and people have gone to see but I don’t think movie star is quite…I’m not on that level.”

Maybe this peripatetic lifestyle is part of protecting against that. Because the moment you live in a house you have a staff of people helping you and they’re all treating you in a certain way…

“Maybe or maybe not; you never know. I think that term, movie star, is a label that’s concocted that really kind of is trying to encapsualize so many things that aren’t real, really, except they exist in print. They exist in journalism and to a certain extent they work as in cinema in the sense of being able to draw a certain amount of people, I guess…”

As we’re talking, grips are moving furniture around and lighting guys are dangling wires overhead, and the cinematographer and director are peering through their lenses and trying to visualize the shot, and Morgan Freeman is walking back the forth in the big board room of the secret organization, perhaps thinking about the scene, perhaps not. And of course there are a lot of people on cellular phones.

Keanu Reeves. To look at a list of his roles is to wonder how the directors of half his movies could have visualized him in the other half, and vice versa. This is the actor who made two of the most harrowing films of all time about teenage angst, “The River’s Edge” and “Permanent Record.” And the same actor who played one of the key predecessors of the dumb-and-dumber movement, in “Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure” and “Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey.” The same actor who was an average, if troubled, teenager in “Parenthood” and an 18th-century rake in “Dangerous Liaisons,” and a male hustler in “My Own Private Idaho.”

He was even in an action movie before “Speed.” It was titled “Point Break,” it was made in 1991, and it combined surfing, sky-diving, bank robbery and Zen. I liked it.

When you made “Speed” in 1994, I said, the industry said it showed that you could make an action picture. (Hollywood has a minute attention span, and had already forgotten “Point Break.”) Is this an action picture, too, or is there another dimension?

“I think Fox wants it to be an action picture, and Andrew Davis and I and Morgan and everyone are trying to make it a little more than an action picture. It’s not a classical action picture; I would say it’s more drama with some action bits thrown in for fun.”

Did the success of “Speed” give you more leeway in terms of career choices?

“Yeah, it did for two years. It’s kind of over now. I mean, I got to do ‘A Walk in the Clouds.’ I got to do a film called ‘Feeling Minnesota.’ It hasn’t come out; we just finished it, with Vincent D'Onofrio, Dan Ackroyd, Cameron Diaz. That got made because I was in “Speed,” you know. The producers said, ‘Okay, we’ll give you $7 million, go make your film,’ you know. Not (ital) just (unital) because I was participating, but that was the last thing that pushed it over.”

So your two years…

“Have run out. Now I have to do something. I don’t know if this will be a hit or not but–this is going to be a tricky film.”

Richard Zanuck was just saying as he was looking at you, “He’s a man now. He’s not a boy anymore.”

Reeves looked slightly impatient. “Well, who knows about that. I don’t know if just how you look makes you a man or not. You could say he looks like a man, maybe.”

I suppose that you’re beginning to get into an age where you can go either way. You have a little more freedom; you’re not just stuck in one age group.

“I hope so. I wanted to have long hair in this because they wanted me to be younger, you know, like 20, say. I’m 31 years old so I thought if I had long hair it’d make me look younger and stuff. But yeah, I mean, hopefully in “Feeling Minnesota,” I’ll look my age, whatever that may be.”

You’ve been working here with Morgan Freeman, and in “A Walk in the Clouds” you were working with Anthony Quinn. Not many people would put them on the same list, but to me they are both very dynamic and vital people.

“Amazing actors. And people.”

But coming from totally different traditions. I mean, Anthony Quinn is a traditional Hollywood movie star who has been around for 50 years in the studio system, and Morgan Freeman is stage trained and really only started acting for movies at a later stage in his life. Do they have different ways of working?

“Well, they’ve had certainly different lives. I mean, Anthony Quinn’s is almost Byzantine. I called him Zeus. But they do actually, more than differences, have similarities. Their technique. The way they love the camera. The way they can embody a moment. Their freedom, their specificity. They can take a scene and make anything in it seem important and they can take any moment and make it light or heavy or the control and who they are. They’re similar in that sense.”

How did you learn to be a movie actor?

“A movie actor? By doing it, and watching other people do it.”

You said they love the camera. How does one love the camera?

“It’s a direction of energy. I’ve seen Morgan and Anthony, even if you’re in the scene with them, if the camera’s over here, they’ll play to the camera. And as an actor in the same environment, you’ll ask, well, what are they doing? But to play it just to me, would not be playing the scene, really. Because it would cut off the camera’s connection to it. The way they do it, they (ital) make (unital) it a scene.”

What could somebody learn from you? You say, ‘I watch other actors.’ Somebody might be watching you. What are they learning?

“I don’t know. There’s a few things, I guess. I mean, it’s kind of a weird thing to say, ‘Well, if you watch me in this film, you could learn this’.”

I don’t mean for you to sound egotistical but just as a pragmatic sort of thing.

“Technique and stuff?”

Or whatever.

“I think I did some good naturalistic acting in ‘River’s Edge,’ some broad comedy and timing in ‘I Love You to Death,’ and ‘Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure.’ I think that there’s some good inner work in ‘Little Buddha.’ I think that there’s some good combination of naturalism and style in ‘My Own Private Idaho.’ There’s some classicism in ‘Speed’…”

When you think of those pictures, you can’t really find the line connecting them. It’s like they’re all points of a star. It’s hard to get from “My Own Private Idaho” to “Bill & Ted.”

“A lot of people don’t take the time, actually, to think about that,” Reeves said, “but what can you do?”

✔ Comments are open.

✔ Directory of recent entries in Roger Ebert’s Journal.

✔ The home page of rogerebert.com.