A few weeks ago, mostly because I could not recall having ever seen it before, I found myself watching the 1963 film “The Wheeler-Dealers” on television one afternoon. A semi-satire on Texas oil billionaires—who were then a popular subject in the media—the film follows the misadventures of Henry J. Tyroon, a smarter-than-he-acts (the big skeleton in his closet is his Harvard education) oilman who, in the need of additional funds, comes to New York City to raise money and finds himself attempting to woo a sexy stock analyst (Lee Remick). As a whole, the movie is pretty silly—the very definition of cinematic fluff—but as dumb as it was, it nevertheless remained completely, utterly watchable and that was due almost entirely to the presence of James Garner in the lead role. His character was kind of a boor but Garner invested him with such sly charm, grace and wit that you not only rooted for him to succeed, you wished that he would attempt drilling in your own backyard to boot.

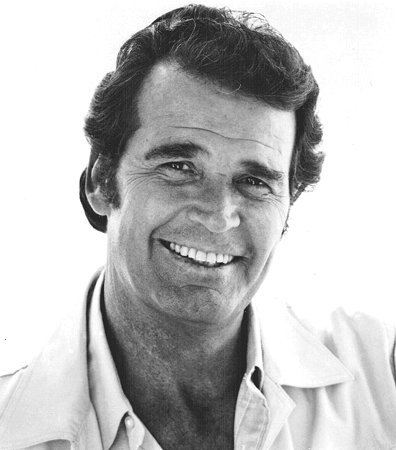

That, in a nutshell, was the secret to Garner’s long-running popularity as a performer on both the big and small screens. He often played characters who were slick rogues who shied away from confrontation or violence—the typical hallmarks of an American screen hero—and who preferred living by their wits than by their fists or their guns. And yet, no matter how cowardly or lazy they might have appeared, it was obvious that when the chips were down, he would finally rise to the occasion on his own terms and make things right. In a sea of anonymous screen he-men, Garner’s more laid-back approach struck a nerve and made him an enormously beloved star. When it was announced today that he passed away overnight at the age of 86, it hit a nerve with people because this was a star that they didn’t just like or admire; people loved James Garner.

Born James Scott Bumgarner in Norman, Oklahoma in 1928, he dropped out of school at 16 to join the Merchant Marines, and, ironically for someone who would play characters that would avoid action at all costs, would go on to win two Purple Hearts in the Korean War. When he returned home, he got the acting bug when a friend got him a job in a non-speaking role on Broadway in “The Caine Mutiny Court Martial”—a job that also saw him running lines with other cast members—and that lead to commercials, small roles on television and his first film appearance in “Toward the Unknown.” After a few more supporting film roles—”Sayonara” (1957) being the most famous of the bunch—he was hired to play the part of an Old West card shark in a new television show called “Maverick.”

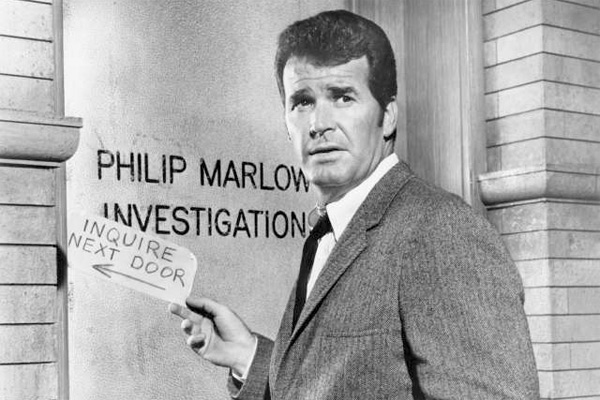

At that time (1957), the airwaves were filled with Westerns but there had never been one quite like “Maverick” and there certainly had never been a character like Bret Maverick. Rather than a solid hero of a man fighting for justice, he was a slick con man and anti-hero who preferred to settle conflicts by utilizing his wit and intelligence over his abilities with a six-shooter. In other words, the show and the character were a rebuke to both the Western genre and the model of the traditional hero, and audiences loved it. Originally designed as a show in which the focus would shift between Bret and his brother Bart (Jack Kelly), it quickly became a star vehicle for Garner, and when he eventually left the show in a salary dispute in 1960, it limped along for a couple additional seasons but was never the same.

Following the show, Garner returned to film, and, while he never quite managed to achieve the same level of stardom that he enjoyed on the tube, he amassed an intriguing number of credits that often found him playing off his amiably roguish persona. Some of his more notable projects of this period include “Cash McCall” (1960), “The Children’s Hour” (1961), “The Great Escape” (1963), “Move Over, Darling” (1963), “36 Hours” (1965), “Grand Prix” (1966), “Support Your Local Sheriff” (1969), “Support Your Local Gunfighter” (1971) and “They Only Kill Their Masters” (1972). While “The Great Escape” is an unassailable classic and “Grand Prix” contains some thrilling racing footage (and Garner would go on to dabble in auto racing in real life a la Paul Newman), the go-to film from this era is “The Americanization of Emily,” a 1964 anti-war satire by Paddy Chayefsky (arguably the best work of his career) that flopped at the time of its release but which has gained a cult following over the years.

In it, Garner plays a naval officer in WWII who, having found combat not to his liking, has been riding out the war in relative comfort as the aide to an admiral (Melvyn Douglas) until a series of incidents, including a romance with English war widow Julie Andrews, ends with him hitting the beach at Normandy on D-Day and…look, just watch it for yourself. Besides being a bracing and hilarious takedown of the usual cliches about combat and heroism, Garner is brilliant in the way that he plays someone who would clearly prefer to be a live coward to a dead hero, but who nevertheless comes across as likable despite his self-serving ways. Garner was said to have considered this to be his best film.

When Garner’s film career waned in the mid-’70s, he returned to television and had his second great success in the medium with “The Rockford Files.” Running from 1974 to 1980, the show featured him as Jim Rockford, a former ex-con working as a private eye, and another character who was the sort to avoid confrontation whenever possible and who frankly preferred fishing to sleuthing. Essentially, Jim Rockford was Bret Maverick transposed to a new era and genre. In Garner’s hands, he became one of the most likable characters on the tube, and by the time the show went off the air, Garner had scored an Emmy and a new generation of fans. After the show ended, he believed he was getting shortchanged on syndication profits and took the astonishing step of suing Universal, who eventually settled with him for an undisclosed amount.

After “Rockford,” Garner returned to film in such projects as “HealtH” (1980), the hit “Victor/Victoria” (1982), the cable favorite “Tank” (1984), “Murphy's Romance” (1985), for which he received his sole Oscar nomination for Best Actor, the big-screen version of “Maverick” (1994), the underrated 1998 mystery “Twilight,” “Space Cowboys” (2000), “Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood” (2002) and “The Notebook” (2004). Not all of these films were especially good but his easy-going presence ensured that they were at least watchable as long as he was on the screen. On television, he appeared in a number of TV movies—including revivals of both of his former series—and received much acclaim for his hilarious turn as Ross Johnson in the HBO adaptation of “Barbarians at the Gates.” He made one last return to series television when he stepped into “8 Simple Rules” in the wake of the unexpected passing of John Ritter and helped that show go on for a couple of additional seasons.

James Garner may never have quite gotten the due that he deserved as an actor because he came across as so cheerful and easy-going that it hardly seemed as if he was doing anything. And yet, to project that sense of ease takes both talent and dedication to the craft and he clearly had both of those in spades. For anyone who has been a student of popular culture over the last half-century, Garner was one of those reliable actors who could always be counted on to supply a good time for audiences. Now that tall dark stranger is gone and while his loss hurts, he at least left us with a huge body of work that will continue to be enjoyed for decades to come.

And, seriously, rent “The Americanization of Emily” right now.