I’ve always felt this way about female impersonators: They may not be as pretty as women, or sing as well, or wear a dress as well, but you’ve got to hand it to them; they sure look great and sing pretty–for men. There are no doubt, of course, female impersonators who practice their art so skillfully that they cannot be told apart from real women–but that, of course, misses the point. A drag queen should be maybe 90 percent convincing as a woman, tops, so you can applaud while still knowing it’s an act.

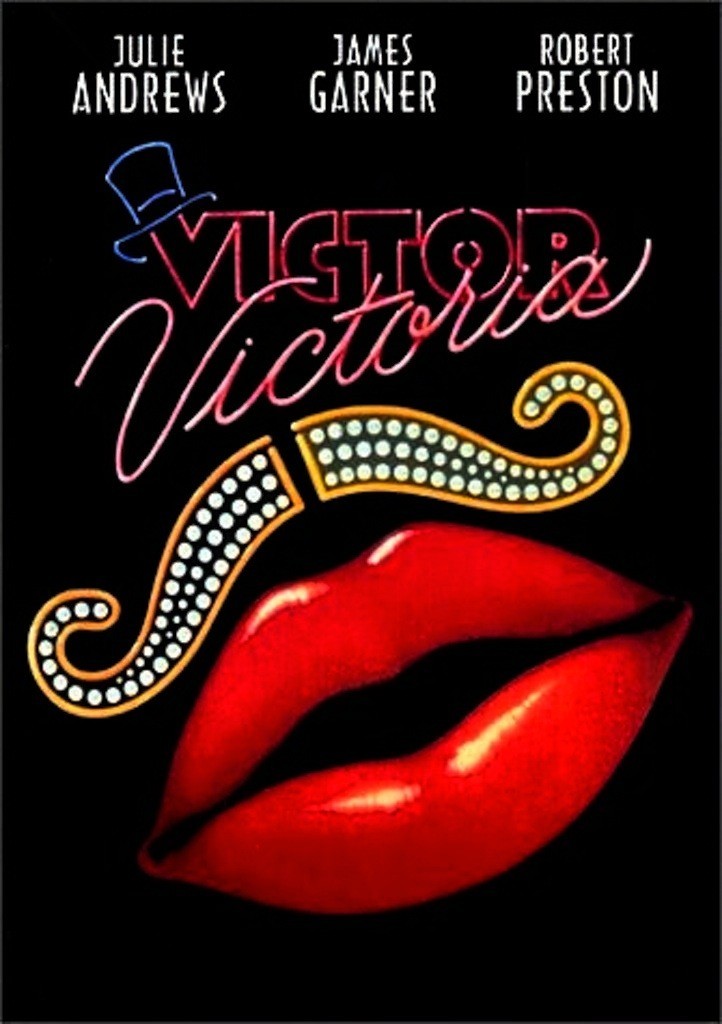

Insights like these are crucial to Blake Edwards’s “Victor/Victoria,” in which Julie Andrews plays a woman playing a man playing a woman. It’s a complicated challenge. If she just comes out as Julie Andrews, then of course she looks just like a woman, because she is one. So when she comes onstage as “Victoria,” said to be “Victor” but really (we know) actually Victoria, she has to be an ever-so-slightly imperfect woman, to sell the premise that she’s a man. Whether she succeeds is the source of a lot of comedy in this movie, which is a lighthearted meditation on how ridiculous we can sometimes become when we take sex too seriously.

The movie is made in the spirit of classic movie sex farces, and is in fact based on one (a 1933 German film named “Viktor Und Viktoria,” which I haven’t seen). Its more recent inspiration is probably “La Cage aux Folles,” an enormous success that gave Hollywood courage to try this offbeat material. In the movie, Andrews is a starving singer, out of work, down to her last franc, when she meets a charming old fraud named Toddy, who is gay, and who is played by Robert Preston in the spirit of Ethel Mertz on “I Love Lucy.” Preston is kind, friendly, plucky, and comes up with the most outrageous schemes to solve problems that wouldn’t be half so complicated if he weren’t on the case. In this case, he has a brainstorm: Since there’s no market for girl singers, but a constant demand for female impersonators, why shouldn’t Andrews assume a false identity and pretend to be a drag queen? “But they’ll know I’m not a man!” she wails. “Of course!” Preston says triumphantly.

The plot thickens when James Garner, as a Chicago nightclub operator, wanders into Victor/Victoria’s nightclub act and falls in love with him/her. Garner refuses to believe that lovely creature is a man. He’s right, but if Andrews admits it, she’s out of work. Meanwhile, Garner’s blond girlfriend (Lesley Ann Warren) is consumed by jealousy, and intrigue grows between Preston and Alex Karras, who plays Garner’s bodyguard. Edwards develops this situation as farce, with lots of gags depending on split-second timing and characters being in the wrong hotel rooms at the right time. He also throws in several nightclub brawls, which aren’t very funny, but which don’t much matter. What makes the material work is not only the fact that it is funny (which it is), but that it’s about likable people.

The three most difficult roles belong to Preston, Garner, and Karras, who must walk a tightrope of uncertain sexual identity without even appearing to condescend to their material. They never do. Because they all seem to be people first and genders second, they see the humor in their bewildering situation as quickly as anyone, and their cheerful ability to rise to a series of implausible occasions makes “Victor/Victoria” not only a funny movie, but, unexpectedly, a warm and friendly one.