Between

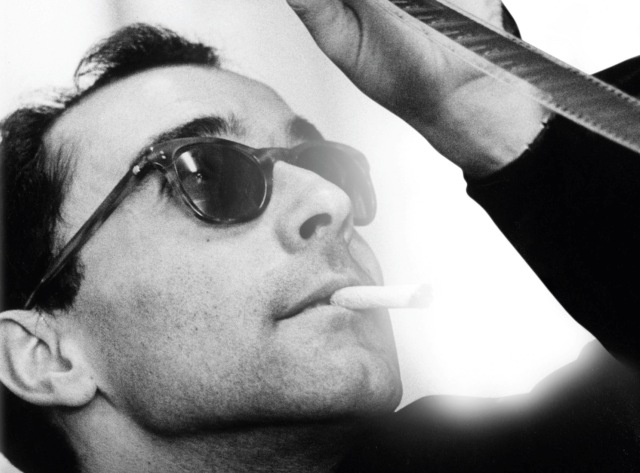

1959 and 1967, Jean-Luc Godard directed no less than fifteen feature films as

well as a handful of shorts and contributions to a number of multi-director

portmanteau projects that were all the rage in Europe at the time. Just by the

numbers alone, this is an impressive accomplishment—outside of exploitation auteurs like Roger Corman, no one,

very few people were averaging two films a year for eight consecutive years.

However, what was far more impressive about this accomplishment was the quality

of the work rather than the quantity—his debut effort,

“Breathless” (1959), was a game changer for the art of cinema along

the lines of “Birth of a Nation” and “Citizen Kane,” and

his subsequent works went even further in redefining forever not only what the

cinema could accomplish but how it could go about doing so. If Bob Dylan and

Thomas Pynchon forever changed what could be accomplished within the parameters

of a song or a novel, Godard did the same thing for film and his influence on

that art form is still felt as strongly today as ever.

Part of

the reason is because Godard himself is still going strong today, creating new

and challenging works at an age when most other filmmakers have either retired

from the game altogether or are content to crank out films that are pale

shadows of their more celebrated efforts. His new film, “Goodbye to

Language,” was lauded when it premiered at Cannes last year for its

innovative use of 3-D visuals and has been receiving critical hosannas since

making its American theatrical debut late last year (including being named the

best film of 2014 by the National Society of Film Critics). In conjunction with

their presentation of “Goodbye for Language” in a three-week run

beginning January 16, Chicago’s Gene Siskel Film Center is presenting

“Godard: The First Wave,” a two-month retrospective running through

March 4 that will present all but two of Godard’s features from his initial

filmmaking breakthrough (with “A Married Woman” and “La

Chinoise” being the sole exceptions) along with a number of his short

films from this period and a pair of his more notable efforts, many of which

will be presented in glorious 35mm. (Those forced to play along at home will be

happy to know that all the films save for the new one are available on DVD and

Blu-ray, with “Every Man for Himself” getting the full special

edition treatment from Criterion at the end of this month.) Here is a brief

tour through the films that will be featured during the retrospective and

granted, 2015 is not even a week old as these words are being written but it is

hard to imagine that there will be very many local cinematic events that could

even hope to top it in terms of importance and pure pleasure.

“Breathless,”

which tells the story of a two-bit French punk (Jean-Paul Belmondo) who becomes

a wanted man when he accidentally kills a cop during a traffic stop while on

his way to see his American girlfriend (Jean Seberg), is arguably the most

well-known and widely seen of Godard’s films and remains a source of cult

fascination more than a half-century since its debut. However, it is by no

means a musty museum piece that can now only be seen from a certain remove as

viewers speculate as to how it must have come across to viewers lucky to catch

it when it first came out. Watching it today is as immediate and engrossing and

radical of a moviegoing experience as it was back in the day. In fact, when you

consider the lazy and logy nature of most contemporary films—works that seem to have been created to fill out a balance

sheet than to fulfill some kind of artistic drive—it

actually seems more daring now than ever before and all the more vital as a

result. Much has been written about its technical and narrative innovations—including such then-radical notions as jump-cuts in the

editing, shooting without artificial lighting and paying homage to the entire

history of the cinema throughout via references and allusions—and indeed, these elements do help make it feel more

contemporary than most other films of its age.

However,

what really drives it home is the palpable screen chemistry between Belmondo

(who was still a few years from international stardom) and Seberg (who a couple

years earlier had been plucked from obscurity to star in Otto Preminger’s

“Saint Joan” (1957) and whose career was thought to be over after its

disastrous critical and commercial reception). Although Godard’s working

methods, such as only giving the actors their scenes on the day they were to be

filmed to keep things fresh, kept them from developing their characters via

conventional methods, their raw chemistry could not be denied. From the moment

the film was released, they were immediately enshrined as one of the most

iconic screen couples of all time. And while this may not have been Godard’s intention, the film also demonstrates conclusively that

Preminger was right in selecting Seberg as the winner of his talent contest

even if he himself had no real idea of how to use her—the quiet ambiguity she brings to her part brings an extra

edge to the proceedings that still fascinates today. Seberg would never again

get a role as strong as she had here, and the sad twists and turns that would

befall her until her 1979 suicide have been documented elsewhere but every time

“Breathless” screens and she chirps “New York International

Tribune,” all of that darkness fades from memory.

Godard’s

next two films, “Le Petit Soldat” (1960) and “A Woman is a

Woman” (1961), could not be more distinct from either

“Breathless” or from each other. The former would find Godard

embracing politics in his work for the first time in telling the story, set in

Geneva during the time of the Algerian War, of a right-leaning journalist

(Michel Subor) working as a spy who falls for a beautiful young woman (Anna

Karina) who, ironically, may working for the enemy. (As this was still a touchy

subject at the time, the film was banned in France for three years and is one

of his more obscure works from this period.) The latter would find Godard

embracing the Hollywood films that he so often venerated during his years

working as a film critic by making a full-color, widescreen romantic

musical-comedy about a stripper (Karina, again) who wants to have a baby. When

her husband (Jean-Claude Brialy) seems less than enthused with the idea, she

looks to his best friend (Belmondo) for assistance. “Le Petit Soldat”

is interesting enough thanks to its rough and jagged cinematic style but is not

exactly entertaining by most conventional means. “A Woman is a

Woman,” on the other hand, is arguably the lightest and frothiest work of

his entire career and while may seem a little too much like a trifle in

comparison with his more acclaimed works, its cheeriness, not to mention the

lovely Michel Legrand score, makes it one of his most instantly likable.

The one

common element between those two films was, of course, the presence of Anna

Karina, who would become Godard’s leading lady both on the screen as well as in

real life, and their next collaboration, “Vivre Sa Vie” (1962), would

prove to be momentous for both their careers. If Godard’s previous films were

the works of a movie-mad kid getting to play with his toys, this was the work

of a mature artist fully in control of his considerable abilities. Told in a

series of 12 stark vignettes, the film follows a shopgirl (Karina) who leaves

her husband and child and becomes a prostitute under the belief that she can

sell her body and still retain control of her soul. Using a fragmented

narrative style as radical as the one employed by “Breathless” that

nevertheless feels at one with the material, Godard recounts her story with

heartbreaking clarity and precision until its still-devastating finale—this may be the most direct and heartfelt work of his

entire career. That certainly extends to his work with Karina—his affection for her, both in real and reel life, burns

through with every frame and the result is one of the great screen performances

of all time. With a filmography like Godard’s, relegating one specific title as

“the best” is a tricky proposition for any number of reasons and most

same people should probably avoid it. That said, I feel perfectly comfortable

in stating that “Vivre Sa Vie” is not just his finest work in my

opinion but it also holds a place in my own personal list of the 10 best films

ever made.

After

“Les Carabiniers” (1963), a dark anti-war comedy about a couple of

dopey farm boys who enlist in the military to seek fortune and glory only to

discover some hard truths about the realities of combat, Godard found himself

involved in his most curious venture with “Contempt” (1963), an

adaptation of Alberto Moravia’s novel “Il Disprezzo” that found him

working with a relatively large budget, in Cinemascope and with a cast that

included such familiar faces (among other body parts) as Jack Palance and

Brigitte Bardot, one of the top sex symbols of the day. By combining such

diverse elements, producers Carlo Ponti and Joseph E. Levine were presumably

hoping for something flashy and easily exploitable, but, rather than bury his

talents, Godard let them flower and the result was a one-of-a-kind work that

allowed him to explore both the disintegration of the relationship between a

screenwriter (Michel Piccoli) and his beautiful wife (guess who) and the

equally tenuous relationship between art and business that crops up when the

screenwriter is hired by a crass American producer (Palance) to write an

adaptation of “The Odyssey.”

Alternating

between the hilarious and the heartbreaking (the centerpiece sequence between

Piccoli and Bardot runs for over 30 minutes and is an absolutely devastating

portrait of dying love), this is arguably Godard’s most accessible film, and

one of his best. Of course, Ponti and Levine hated it and insisted that the

only way that they would release it would be if Godard went back and shot a

nude scene with Bardot that they could use as box-office insurance. The result

was the film’s knockout opening scene, a sequence that, like the rest of the film,

offers up the expected ingredients in unexpected and eye-opening ways. (Bardot,

by the way, is excellent in the film and offers evidence that there was a

strong actress beneath the sex bomb exterior.) Considered a flop at the time,

it is now regarded as a classic and as a must-see for any serious student of

the cinema.

Having

thoroughly disliked the experience of working on a big-budget film, Godard went

back to his low-budget roots and made a series of entertaining and increasingly

provocative films that used classic cinematic genres as a launching pad for

stories that mixed the complications of human relationships with

homages/commentaries on the classic Hollywood narratives. “Band of

Outsiders” (1964) tells the story of a couple of friends (Sami Frey and

Claude Brasseur) who both fall for the same classmate (Karina) and, after such

now-famous hijinks as a run through the Louvre and dancing the

“Madison,” the three launch a half-assed plan, largely inspired by

old gangster movies, to rob a house belonging to her aunt.

“Alphaville” (1965) was a science-fiction tale in which American

secret agent Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine) travels to another planet to the

titular city, a place where love and emotion and even certain words have been

eliminated, in order to find a missing fellow agent and convince the venerated

Professor von Braun to return to Earth with him, falling in love along the way

with the professor’s daughter (Karina). “Pierrot Le Fou” (1965) was

his take on the lovers-on-the-run subgenre in which a bored middle-class

husband and father (Belmondo) runs off with his family’s sexy babysitter

(Karina) to the Riviera and gets mixed up with a number of shady characters in

events that lead up to a literally explosive finale. Loosely based on a Donald

E. Westlake novel (which Godard did not acquire the rights to, leading to a

lawsuit that kept the film out of circulation in America for nearly 40 years),

“Made in USA” (1966) is a strange mixture of mystery and social

satire with Karina (in what would be her final performance for Godard) as a

private eye on the trail of an of old lover who may or may not have been

murdered by political forces.

With its

anti-capitalist leanings and such touches as giving a couple of minor criminal

characters the names Nixon and McNamara, “Made in USA” (1966) found

Godard beginning to shift his focus from cultural politics to the increasingly

turbulent times going on in the real world. (As Karina puts it at one point,

“We were in a political movie. Walt Disney with blood.” He would

continue to move in that direction with his next few projects: “Masculine

Feminine” (1966), a story about and for “the children of Marx and

Coca-Cola” took on sex, politics and popular culture through the prism of

the increasingly shaky romance between a pseudo-radical (Jean-Pierre Leaud) and

a pop singer (Chantal Goya); “2 or 3 Things I Know About Her” (1967),

which largely broke from conventional storytelling to observe the daily

existence of an ordinary suburban housewife (Marina Vlady) who helps make ends

meet by secretly working as a prostitute. In his contribution to the omnibus

documentary “Far from Vietnam” (1967), a project in which a number of

leading French filmmakers made a short protesting the war, Godard sat behind

his camera and announced that since he was unable to actually go to Vietnam for

himself, his form of protest would be to mention it in his subsequent films.

As Godard

became more interested in radical politics, his interest in formal narrative

procedure waned considerably and with “Weekend” (1967), he made what

he conceived to be his final statement in regards to conventional cinema. In

this still-startling black comedy, a deeply unpleasant bourgeois couple (Jean

Yanne and Mirielle Darc)—each of whom is planning to do

away with the other in order to go off with their lover—set off on a road trip to her dying father’s country home

in order to secure her inheritance and help speed up the process if necessary.

Along the way, they encounter a number of bloody car accidents and traffic jams

(including one seen in an extended tracking shot lasting over nine minutes

before getting to its grisly conclusion) and have their own car destroyed

before they eventually fall in with a group of radical hippies whose ethos has

expanded enough in order to embrace cannibalism as a way of life. While most

agitprop of the time has not aged particularly well, Godard’s cinematic Molotov

cocktail, made of equal parts cynical humor, revolutionary spirit, outrage and

despair, still packs a wallop for viewers today. In bringing an end to the

first phase of his career (he even ends the film with title cards famously

reading “End of Film. End of Cinema”), it remains a deck clearer for

the ages.

For many

observers, Godard’s story ends there but while his films would become more

difficult to see in America, he continued to work steadily on a number of

projects that largely eschewed formal narrative entirely for works that showed

more interest in radical politics and daring experiments with the most basic

elements of cinema, namely how people hear and see film. (Many of these films

showed him doing pioneering work in the new medium of video.) After a decade or

so of such experimental work, he embarked on a new phase of filmmaking in 1980

when he returned to the world of narrative filmmaking, albeit on his terms and

in ways that allowed him to continue his groundbreaking work with sound and

image, with “Every Man for Himself,” in which he took a plot about a

triangle of sort developing between a film editor (Nathalie Baye) in dire need

of a change in her life, her filmmaker lover (Jacques Dutronc) who is fearful

of making a commitment and a prostitute (Isabelle Huppert) who quietly bears

all the abuse heaped upon her while contriving to finally take charge of her

own life. With its bold advances in style, including the numerous points in

which the film itself slows down until it moves practically frame by frame and

deliberately jarring sound design, the film presents viewers with something

that is not so much a story as it is a meditation on a story and while it may

alienate some even to this day, it is nevertheless fascinating to watch the

rebirth of an artist ready to set off on his own unique path once again.

That

journey continues to this day and while his output since then would not prove

to be the equal of his first phase, there would be a lot of fascinating films

along the way. One of the most infamous of this period would be “Hail

Mary” (1985) his enormously controversial modern-day retelling of the

birth of Christ in which Mary (Myriem Roussel) is a basketball-loving student,

Joseph (Thierry Rode) is a cab driver and Uncle Gabriel (Philippe Lacoste)

arrives via jet plane to announce that the virginal Mary will give birth to the

son of God. At the time it was made, the film inspired protests around the

world from outraged Catholics who assumed that Godard was somehow casting

aspersions on one of the most important tenets of their faith. Most of these

protesters clearly had not seen the film because if they had, they would

realize that rather than mock the story, he was using the modern-day narrative

as a way of exploring it in a thoughtful manner designed to explore what might

go through the mind of an ordinary young woman placed in such an extraordinary

situation. Now that the hubbub has died down (I don’t expect any protests at

the screenings, though a part of me wishes that there would be, if only for old

times’ sake), hopefully this will

become more apparent to viewers and the film can finally be considered one of

the most provocative and moving examinations of faith to appear on a movie

screen in the last thirty-odd years or so.

Finally,

there is “Goodbye to Language” and even as someone who has been

enthralled with much of Godard’s latter-day efforts, I was quite simply blown

away by what he had to offer this time around. From a narrative standpoint, it

is the usual stew of Godardian concerns about love, death, war, cinema and the

gradual loss of communication and self in a world overrun by technological

advances that only serve to isolate people further, all of which is projected

by a loosely conceived story involving a pair of adulterous lovers, her

murderous husband and a happy dog. Actually it may be two separate couples or

two different version of the original couple—it

is that kind of movie. (There are even brief appearances by Lord Byron and Mary

Shelley to help fill things out.) That is all interesting but what transforms

the film from the merely interesting to the flat-out stunning is his stunning

use of 3-D photography. On the surface, the idea of a 3-D Godard film sounds

like a joke, but the effects that he achieves here put virtually every other

use of the process that I have ever seen to shame, both on a technical level

and in the way that he uses the added dimension to genuinely bring something of

value and interest to the story. In the most eye-popping moment, Godard and

cinematographer Fabrice Aragno have figured out a way to superimpose image in

such a way so that there is literally a separate image for each eye to observe.

I may not be explaining it too well but trust me, you will know it when you see

it and when you see it, you will never forget it.

There are

many things to love about “Goodbye to Language”—the gorgeous visuals, the head-spinning commentary that

invokes everything from philosophy to classic literature to clips from

“The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” the fact that it is, for all of its

metaphysical concerns, just plain fun to watch—but

the best thing about it is the way that it demonstrates conclusively that

Godard is as vital and relevant today as he was back in his original heyday. He

is 84 now, an age when most filmmakers have either retired to the Lifetime

Achievement Award circuit or, if they are still working, are mostly pushing out

films that are merely shadows of their best work. Instead of those options,

Godard has been and continues to push the boundaries of the art form of cinema

in wholly unexpected and profoundly radical ways that may one day prove to be

as influential as his earlier efforts. In other words, Jean-Luc Godard may well

be, from an artistic standpoint, one of the youngest filmmakers at work today

and bless him for it. More than ever, we need people like him to open our eyes

to the possibilities of film, and when he does eventually leave the scene, it

will be a dark day indeed, though there will be the compensation of one of the

great bodies of work in the history of the medium.