This month’s issue of online magazine Bright Wall/Dark Room is focused around science fiction films. In addition to the essay below by Elisabeth Geier on “The Man with Two Brains” and “All of Me,” the May 2016 edition includes pieces on “Midnight Special,” “Blade Runner,” “Super 8,” “Mad Max: Fury Road,” “Her,” “Another Earth,” “Sunshine,” “Advantageous” and “The Bed-Sitting Room.”

You can read previous excerpts from the magazine here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or purchase a copy of their current issue, go here.

In first or second grade, a visiting science teacher asked my class if we thought two objects could occupy the same space. We stood facing each other in parallel lines and stepped forward when instructed, decreasing the space between us every time. Closer, closer, until we met inside a taped-off carpet square.

“Do you think you’re in the same space now?” the teacher asked.

Of course we are, look, we’re both inside the lines. Some kids hugged or pressed together back-to-back, as if they could fuse on site.

“No two objects can occupy the same space,” the science teacher said. “No matter how close you get, there’s still space between you. Even water in a glass doesn’t take up the same space as the glass or the air. The air goes somewhere else. That’s displacement.” I may be remembering the details wrong, but I remember the feeling: our tiny minds were blown. No matter how close you get, you’re always apart.

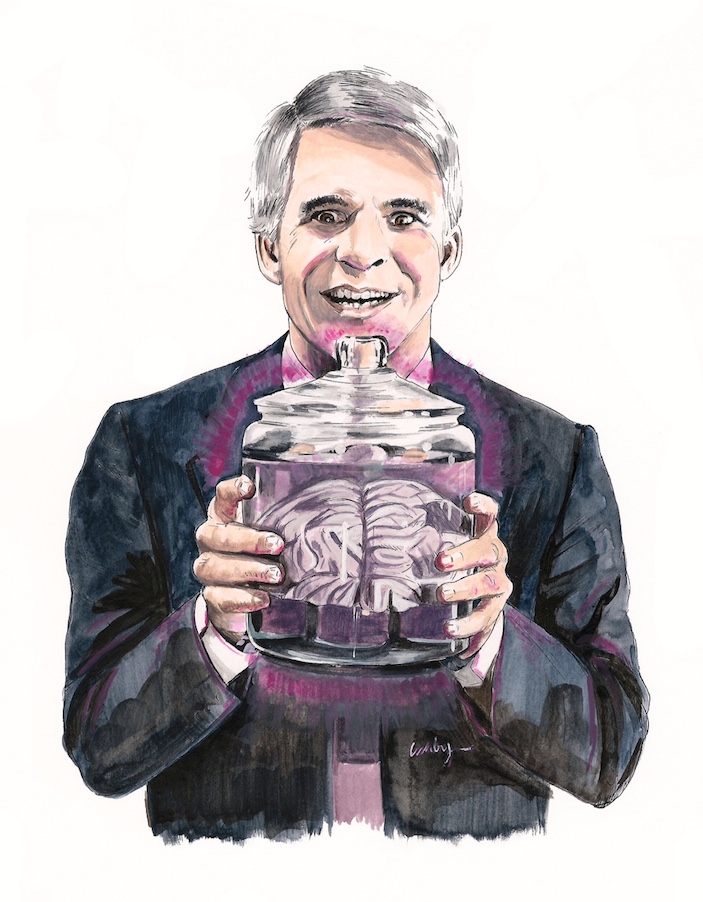

In the early 1980’s, director Carl Reiner and comedian Steve Martin collaborated on two films that challenged the laws of physics. “The Man With Two Brains” (1983) was first, the story of Dr. Michael Hfuhruhurr (Martin) and his beloved, Anne Uumelmahaye (voiced, uncredited, by Sissy Spacek). Michael is a brain surgeon who invented the “cranial screw-top” method. Anne is a recently deceased woman whose brain is kept alive suspended in goo. They meet in the home/workplace of Dr. Necessitor, an ambiguously European scientist who promises to show Michael how to “take the thoughts and data from a dying brain and transfer them into another body without opening the skull.”

When Dr. Necessitor leaves the room to attend to an angry wife (a running theme in this film: all women except Anne are either sex objects or monstrosities, sometimes both), Michael starts singing a song, and pretty soon a woman’s voice joins in. It is Anne, chiming in from her jar on a shelf. For some reason, thanks to a lucky twist of fate and fantasy, they can communicate telepathically. Their first meeting has no awkward small talk or physical mishaps. All Anne has is a mind, and their connection is so immediate, brain-to-brain, that it doesn’t matter what she looks like (she looks like a brain in a jar) or how she smells (she probably smells like a brain). They are instantly in love.

Internet dating, which I started again recently after several years away, is a lot like browsing brains on a shelf. We distill ourselves into quick, catchy profiles and exchange carefully crafted messages separate from body language and sense. Our complex humanity is reduced to personality and intellect floating in goo. It’s all too easy for me to fall in like with a witty writer whose profile blends humor, a bit of vulnerability, and maybe something about a dog. But at some point, bodies have to get involved, and that’s when things tend to fall apart.

My first first date in over three years was with a recently single guy who was leaving within a week for a months-long earthquake reconstruction mission in Nepal. We agreed it was a “practice date.” He was moving out of the country, I was testing the waters to find out if I was emotionally ready to date. There were no expectations. It felt easy. But dates by nature require vulnerability and sharing of the self, and despite our arrangement, I had trouble dealing with the aftermath of our encounter. I learned all about this dude: his sci-fi novel in progress, his Alaskan upbringing, the time he met Alan Tudyk, how they took a photo together alongside his ex, and how after the breakup he created two copies of the picture with the other party removed so they could each have a photo of them alone with Wash from “Firefly.” We spent several hours talking and learning all about each other, and then we were supposed to just go our separate ways? It didn’t seem right.

I went home and felt incredibly melancholy. This “practice date” felt like a distillation of all dates, the encapsulation of what I hate about dating, the expectations and boundaries that make it difficult to just learn about someone and decide if you like them and hope that they like you too. I guess it’s my own fault for thinking I could handle something casual when I am the opposite of casual, and for forming attachments so quickly and conflating pleasant conversation with deep connection. Or maybe it’s dating’s fault, the whole stinking enterprise, the combination job interview/emotional leap of faith that so often ends in never seeing each other again. You’re left holding on to pieces of another person’s character with no place to put them (unless you’re me, and you put them in writing and cross your fingers that this nice Alaskan guy doesn’t have internet access in Nepal). Plus, there’s the whole issue of whether or not to touch this body you just met, and whether the brain-browsing connection that led to a date equals physical attraction that leads to more… it’s all rather confusing. To be single and to mingle is not much fun.

In “The Man With Two Brains,” Michael and Anne’s future happiness depends on the physical element. Anne needs a body soon, or her intellect will die. The film was written by Reiner and Martin just a few years after “The Jerk,“ and it suffers from being in “The Jerk’s” shadow—a lot of the jokes feel like leftovers, and it seems a stretch for Martin to be wild and crazy in a non-Navin Johnson way. But there’s something charming in the story of this man and his second brain, their immediate connection and ensuing journey to get her into a body before time runs out. When I first saw the movie as a child, in addition to thinking Steve Martin was the funniest human alive (an opinion that sticks with me to this day, though his film career has taken some strange turns), I thought it was incredibly romantic: Steve Martin is in love with this smart, funny lady, and he doesn’t even know if she’s physically attractive. “The Man With Two Brains” makes a strong case for intellectual attraction.

After another first date with someone perfectly nice who was cute in pictures and funny over text but didn’t do it for me in person, I told a friend, “I don’t feel intellectually engaged, and that’s, like, super important to my dumb brain.”

“I approve,” she said. “And your brain isn’t dumb.” Very kind, given how often I use “super” as a qualifier. But the heart wants what it wants, and the brain needs what it needs, and the body, my body, follows the brain.

“The Man With Two Brains” is not a good film. It’s full of misogyny and violence dressed up as juvenile jokes. There’s a serial killer who takes down women in elevators, and Kathleen Turner as Dr. H.’s monstrous, gold-digging wife, plus this whole side thing with a gorilla that hardly bears mentioning, but how can I not mention a gorilla. It’s all a bit much. Still, in the midst of all that much-ness, Michael and Anne’s courtship is rather sweet. Because all they have are each other’s intensely compatible brains, they jump right into a comfortable intimacy, spending hours talking about whatever. He takes her on a romantic date in a rowboat. He places a straw sun hat tenderly atop her jar. “For the first time,” he says, “I’m aroused by a mind,” and he kisses a pair of waxed lips bought special for the occasion. For all its silliness, it’s a lovely scene.

Minutes later, Michael’s jealous, monstrous wife sticks Anne’s jar in an oven and cranks the dial. She survives, but she loses her nines. (“Count to ten,” Michael says, and Anne counts: “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, ten.”) Let me be clear: this movie is exceptionally stupid. But then, so is the concept of romantic love.

I got my heart broken recently, in case that wasn’t obvious. I mean really good and smashed, ambushed, dessiccated, ripped out and stomped. For months afterwards, I avoided all media concerned with romance and love. I watched endless episodes of “The Great British Baking Show” and other toothless TV. I quit listening to music, which is only ever about romance and love, and mainlined a podcast series about the Charles Manson murders. I was not well. I understood for the first time how crimes of passion occur, how jilted lovers key cars and set fires in the wake of their trauma. I had recurring dreams about punching my betrayer in the face. Friends commended me for handling things relatively well, and I told them, “Just because I’m not doing terrible things doesn’t mean I’m not thinking about them, and how easy they would be, all the time.”

After his beloved brain almost eats it in an oven, Michael Hfuhruhurr cracks. He can’t risk losing her, not when they just found one another, and so he starts searching for a body to house her mind. Driven mad by love and desire, he stares menacingly at every woman he sees. He hires a prostitute with the intention to kill her and transfer Anne’s Anne-ness into the corpse. The film goes off the rails, but in the end, of course, it all works out. Anne finds a body without Michael needing to commit violence, and they live happily ever after. That’s what the movies are for.

There’s another, better early 80’s Steve Martin/Carl Reiner collaboration in which Martin meets a disembodied woman and spends half the movie scheming to transfer her personhood into a desirable shell: “All of Me” (1984). This time around, Martin is Roger Cobb, an attorney/musician in the midst of an existential crisis. The film opens on his 38th birthday, when he asks his soon-to-be-ex-girlfriend, “What am I doing with my life? What am I doing with my career? What am I doing with us?” What are any of us doing with anything, honestly?

Roger’s life changes when he is assigned to oversee the will of invalid heiress Edwina Cutwater (Lily Tomlin, radiant being of pure light). Edwina is on death’s door, and plans to “come back from the dead” by transferring her soul into the younger, healthier body of her stablehand’s daughter Teri (Victoria Tennant,). Roger and Edwina hate each other from the start. He thinks she’s spoiled and insane, and she thinks he’s defiant and unhelpful. Of course, they’re bound to end up together.

During Edwina’s soul-transferring ceremony, things go terribly awry. To quote the movie trailer: “They put her soul in a bowl, but things got out of control.” Edwina ends up residing inside of Roger, sharing his thoughts, controlling the right side of his body while he retains control of the left. “Your foot, my foot, your foot, my foot,” they chant as they stagger down the sidewalk, Martin’s body contorting wildly as he embodies two souls in one.

Aristotle supposedly said, “Love is composed of a single soul inhabiting two bodies.” It’s a nice idea, but I like All of Me‘s stance better: love happens when two souls get very, very close. Roger and Edwina are forced to occupy the same space, and they spend much of the film fighting. He wants her out of his body, and she wants in to her second chance at life. But eventually, they learn that everything is easier when they cooperate. They go from hate to love, and sure, that dynamic is a romantic comedy trope, but here, it’s an example of real emotional intimacy. It feels a lot more grown-up and realistic (as realistic as a movie about soul-swapping can be).

It’s certainly truer to my own experience of love, not as a magical, mystical meeting in the night and the discovery that we are two halves of the same being, but as an investment of time and attention, a slow-growing intimacy and the acceptance of another person’s humanity, flaws and all. Of course, that’s why first dates are so difficult. My last love story didn’t work out, and knowing how much time and energy it takes to get to know another soul makes a second attempt feel daunting. Maybe I’m just cynical. Maybe I haven’t experienced the right kind of love. Or maybe there is no “right” kind, and true love is as realistic as brains in jars and souls in bowls.

It’s very appealing, the idea of slowly learning to love a person who falls into your life (or whose soul falls into your body). To occupy the same space as your beloved, to share thought and movement and have nowhere to hide. It sounds like a nightmare, but it also sounds like release: you have no choice but to love the one you’re with. Real-life relationships are the grade school science experiment with impossible stakes. The closer you get to your beloved, the clearer the distance between you becomes. At best, that distance is edifying (I used to think my partner and I were a hovercraft, gaining power from displacement, the right amount of distance keeping us aloft). At worst, it’s what ultimately drives two people apart.

At the end of “All of Me,” when Edwina is finally in her new body, Roger asks her how she feels.

“Alive. Healthy,” she says. “Scared.”

“Why?” he asks.

“I finally got what I always wanted,” Edwina says. “Now, no excuses anymore.” Edwina’s old life was one of protection and fear, hiding behind her money and her illness. Now, she’s in the flesh, in love, and facing all the messiness that entails.

“Welcome to the real world,” Roger says.

On my most recent first date, I mentioned that I was re-watching “The Man With Two Brains” and “All of Me” and trying to write about them.

“They’re not necessarily good,” I said, “but I love them. I just have to figure out what to write besides ‘I love these movies.’ I need to come up with a reason anybody else should care.”

A few hours into our date, we wound up roaming the aisles of a video store—this is Portland, where such oddities still exist—and came across an entire Steve Martin section. We pointed out our favorites, and joked about how Martin perfected the role of Dentist in “Little Shop of Horrors” decades before “Novocaine” came out. We bantered. It was a really good date. We should be kissing in a rowboat by now. I thought at least we’d see each other again.

We haven’t. Probably we won’t. Once again, I’m left with knowledge of a person, the space between us, the promise that I felt, and a bit of embarrassment that I believed, even for a moment, that it could be something more.