We are pleased to feature an excerpt from the July 2017 edition of the online magazine Bright Wall/Dark Room, which has theme of Sex and the Movies. It’s their largest issue to date, though still available online for just $2.99. In addition to this “Secretary” piece by Kara Shroyer, they also have new essays on “Atonement,” “The Sessions,” “Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde” (1931), “Quills,” “Teeth,” “Alice in Wonderland: An X-Rated Musical Comedy,” “Spring Breakers,” “Anomalisa,” “Margarita with a Straw,” “I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone,” a look at the sex scenes in Bryan Fuller’s work, and more.

You can read previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or purchase a copy of their current issue, click here.

Nothing human is alien to me. — Terence

What makes onscreen sex good?

Is it the lighting? The direction? The music?

Does it matter how attractive the actors are? How much of their bodies they’re paid to reveal?

Is it how much we laugh or gasp while watching it, or how many fingers we have to peek through? How turned on we feel by what we see?

Does gender matter? Sexual orientation? Mutual orgasms, multiple positions?

And who’s having sex in good sex scenes? Strangers? Married people? Old people? Multiple people? One person? Teenagers? The mentally ill? The disabled? The incarcerated?

Can a good sex scene include violence, punishment, and pain?

Does a good sex scene even have to involve intercourse?

Before I began writing this piece, I asked a few friends about their favorite sex (or sexy) scenes in film. I’d recommend this exercise; you’ll learn a lot about your people. I was delighted with all of their answers: The Notebook, Cold Mountain, Mulholland Drive, Magic Mike XXL, Titanic, Atonement, andso many others. But I was waiting for one particular answer, and I got it.

“Mine is probably that first spanking scene in Secretary, so….”

Yes, I thought. Yes! Don’t stop!

Long before E.L. James published her runaway bestseller, Fifty Shades of Grey in 2011, and before Sam Taylor-Johnson brought it to the big screen in 2015, there was Secretary (2002). Adapted from a short story by Mary Gaitskill, and directed by Steven Shainberg, this dark comedy explores the inner life of two characters involved in a dominant-submissive relationship.

Lee Holloway (Maggie Gyllenhaal) is adjusting to life again after being institutionalized for an incident of self-harm. She’s living with her parents, learning to type, conducting a rather lukewarm romantic relationship with a guy from high school, and trying desperately not to fall into her old, dangerous habits again. One day, trying unsuccessfully to dispose of her secret stash of sharp instruments, she finds the classifieds in the garbage, and lands a job as a secretary for one E. Edward Grey (James Spader), an eccentric attorney, who hires her despite her poor social skills and unprofessional attire.

At first, Grey is irked by Lee’s typos, physical habits, and other harmless mistakes, but it soon becomes clear—to both attorney and secretary—that he’s sexually aroused by her obedient behavior.

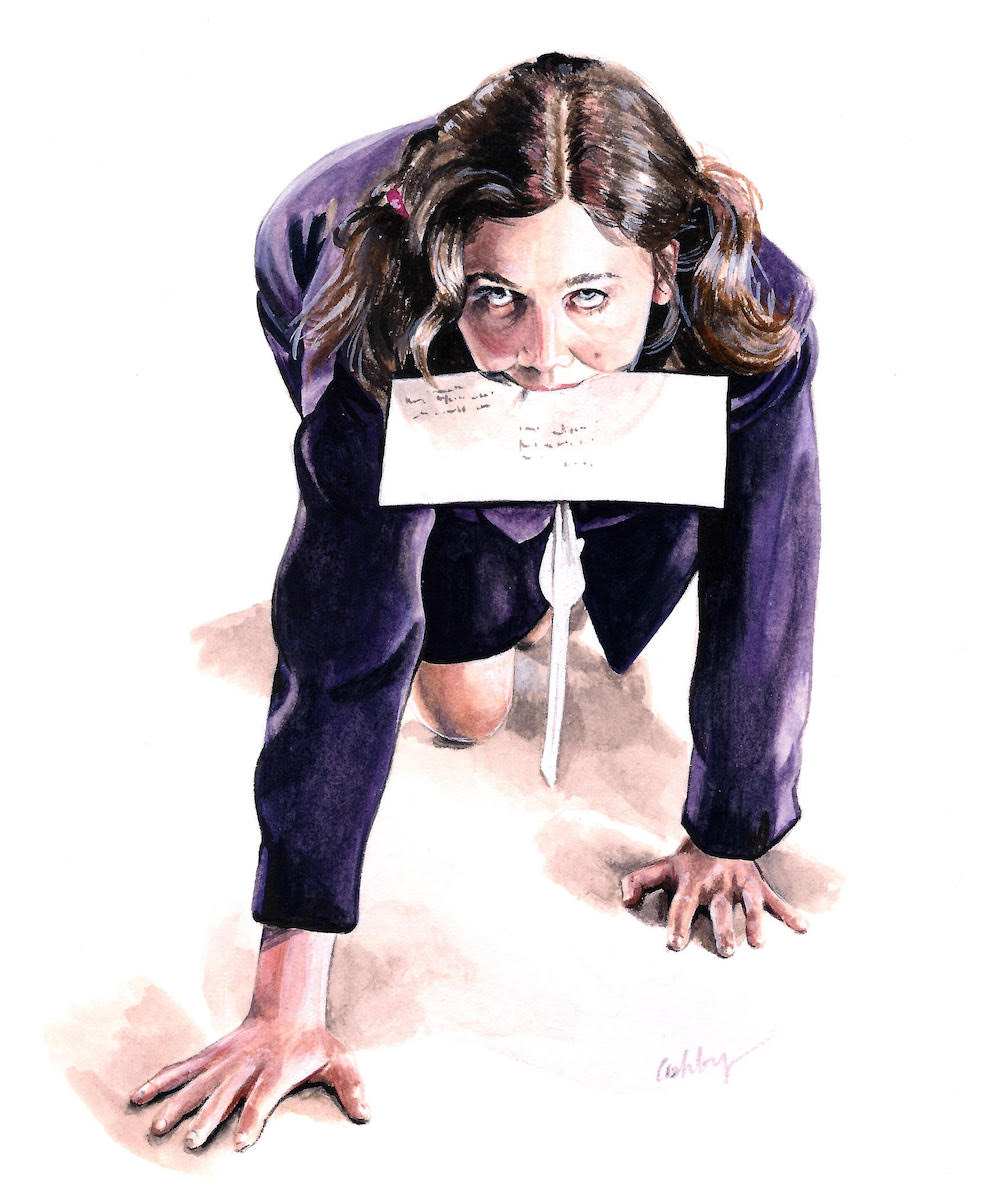

It’s hard to think of an actor who could pull Lee Holloway off with more aplomb than Gyllenhaal. She possesses a sort of rumpled sensuality, like she’s just woken up from a nap—clothes askew, hair tangled, makeup smeared. Her stooped shoulders and plodding gait call to mind the adolescent years, when budding attraction to others is often outweighed by discomfort in our own skin. But as Grey subjects Lee to increasingly humiliating tasks—moving around on all fours to re-bait and replace mouse traps, digging through the dumpster for a lost case file—and as she bumbles her way through them, she begins to regain her dignity, self-possession, and sexuality. Unlike her spiritual successor, Anastasia Steele of Fifty Shades of Grey fame, Lee Holloway isn’t stuffing herself into the submissive mold to win her man. She steps into it as unwittingly as she steps into E. Edward Grey’s office.

The transition from unorthodox professional relationship to overtly dominant-submissive relationship occurs in a moment of tenderness and vulnerability. Grey calls Lee into his office, offers her hot chocolate, and commands her to never cut herself again. At first, though Lee acquiesces, she laughs a little, lowers her eyes. How will she be able to obey this order? After all, how many times have others issued the same command? How many times has she given herself the same injunction?

“Why do you cut yourself, Lee?” Grey asks gently.

“I don’t know.”

What he says next shocks her: “Is it that sometimes the pain inside has to come to the surface and when you see the evidence of the pain inside, you finally know you’re really here? Then, when you watch the wound heal, it’s comforting. Isn’t it?”

I once read a “Modern Love” essay where the author explained (more eloquently than I’ll be able to) that in order to love herself, she first had to find someone who loved her. This idea has stuck with me ever since. Of course, in a world where all relationships work as they should—a world where we are nurtured by our parents, encouraged and challenged by our teachers, respected by our peers, and loved unconditionally by our friends and paramours—this statement sounds ludicrous. But as Lee Holloway knows all too well, the world doesn’t work that way. Parents are anxious, alcoholics, or abusive; teachers are tired or unqualified; friends are sad and selfish; lovers are greedy, needy, and angry. There are no rules to these relationships, no guarantee that any specific behavior will garner the type of attention or care required. Looking in the mirror, all we can see are the ways we have failed ourselves and others. Our experience of love is often inextricably linked to pain.

When we think of pain, what usually comes to mind is unproductive pain. It’s pain without purpose or reason; it is senseless, violent, and usually traumatic. Unproductive pain is self-serving, self-perpetuating, and chaotic. Unproductive pain is parents who don’t show up, physically or emotionally; it’s partners who hurt us for sport. Unproductive pain is the pain we inflict on others when we use relationships for our own benefit or pleasure without a thought for our partner’s long-term good.

And then there’s productive pain. I’ve never given birth, but many of my friends have, so I’ve heard a lot about this concept: that there is good pain, pain that tells you, “This hurts like hell, but something good’s going to come of it!” Productive pain tells your body what resources it needs to heal, tells you how far you can run or how much you should carry. Productive pain brings resolution. Inside a relationship, productive pain happens when your weaknesses get down and dirty with your partner’s weaknesses. Productive pain is sacrifice and compromise. If love—and the making of it—is the ultimate creative act, then, like all creative acts, it will require several drafts, each one a small death (“la petite mort”) to self in favor of the other.

So, when Lee agrees a second time to never harm herself again, we know, as she does, that she won’t, because she’s doing it for Grey. She’s giving up her first love for a new love, old pain for productive pain. Grey gives her the rest of the day off, and, at his order, she walks home through the park.

“I took a shortcut through Hawkins Park, and it was as if I’d never taken a walk by myself before,” she narrates. “And when I thought about it, I realized I probably never had taken a walk alone. But because he had given me the permission to do this, because he insisted on it, I felt held by him as I walked alone.”

The next day, after Lee makes a typing error, Grey spanks her for the first time.

As she bends at a 90-degree angle over his desk, her heavy-breathing boss administering the punishment, Lee gasps in pain and humiliation. But as she looks over her shoulder into her employer’s face, she also flushes with surprise and arousal. She knows how to type slower, to watch her fingers hit the right keys; she knows how to use white-out. But her mistakes continue, and his voice crackles regularly over the intercom, like a summons from wronged parent to errant child: “My office, now, Miss Holloway!”

In her employer, Lee finds a surprising home for her feelings of inadequacy, and an alternative to self-harm that inflicts pain, but also, surprising pleasure. In E. Edward Grey’s office—which, as Roger Ebert aptly put it, “looks like the result of intense conversations with an interior designer who has seen too many Michael Douglas movies”—the rules are clear. Typos, sniffling, playing with her hair, or taking her shoes off under the desk all warrant spankings. His commands soon spread beyond the office: he dictates her diet, tells her how to dress. Later, Lee ogles her own typo-ridden transcripts—slashed through with Grey’s red pen—and moans his stern mandates as she masturbates at home, then in the handicapped stall at work. Under Grey’s callous care, she flourishes like one of the exotic orchids in his collection. The more Grey punishes her, the more Lee stands tall, walks with her hips, wears more flattering clothing, higher heels. She is finally known, and in being known, can know and love herself.

It’s not all fun and handcuffs, though; the relationship begins to take a toll on Grey. “We can’t do this 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” he complains. Whereas Lee finds release, Grey is increasingly disgusted by his own behavior. His obsessive-compulsive disorder, barely under control, begins to affect his relationship with his clients.

“I’m shy,” he tells Lee, but other than this, his OCD, and his predilection for sadism, Grey is a mystery. At one point, before he burns it, we get to peek inside a folder where he keeps Polaroids of all his former secretaries. This brief glimpse into his private world asks more questions than it answers.

Has he done this before? Is this the latest in a series of failed dominant-submissive relationships? We recognize one of the women in the photographs. She’d been crying and packing up her belongings the day Lee arrived to replace her. Was this nameless secretary crying because she found Grey’s behavior cruel, or because she found it so sexually satisfying that, out of disgust at himself, he turned her away?

Sadists are often portrayed as cruel control freaks who possess a dangerous cocktail of narcissism, hunger for power, and lack of empathy. (Think: Marcel in Belle de Jour, Frank Booth in Blue Velvet, Christian Grey in Fifty Shades, etc.) But E. Edward Grey is different. He feels as much self-loathing as Lee does; his own desires disturb him. He may get sexual pleasure from hurting and humiliating Lee, but sexual pleasure isn’t enough. He needs more.

In an interview after the film’s release, James Spader shared that he was originally drawn to the role because it would give him a chance to explore a psychology alien to his own. (Spader has become known for portraying the eccentric, the bizarre, and the downright evil, so his interest might be unsurprising.) And while I’m fascinated by E. Edward Grey for the same reason, I also believe that his urges are far more common than we know.

Unlike Fifty Shades of Grey, Secretary never exploits or stereotypes BDSM for sport; never uses it as a sideshow; never markets it as a pathology to overcome. Fifty Shades’ BDSM is a shiny lure, a provocation; it’s not an extension of the characters’ existing relationship but a character itself, and an underwritten character at that. In Secretary, the dominant-submissive dynamic is an inevitable consequence to both characters’ psychologies, personalities, and desires. As a result, Secretary reaches levels of eroticism that Fifty Shades can only tease.

Done well, onscreen sex—and I use this word as an umbrella term to describe all sexually-charged encounters—works to defy, develop, or delineate what’s happening between two (or more) characters at any given time in the story. Done well, a sex scene steps into the unspoken, deeply personal and often uncomfortable space between characters, where any fireworks, fumbles, fantasies and foreplay are—or seem to be—for them, rather than for us, the viewer-voyeurs. Done well, sex scenes tell us secrets. Done well, they ask us to cover our eyes and please close the door on our way out, because we’ve stumbled onto sacred ground. Done well, onscreen sex seems inevitable. Without it, our understanding of the characters involved would be incomplete; the narrative wouldn’t resolve; and most importantly, we wouldn’t know what we now do.

I understand now, in a way, why the Christian community I grew up in has worked so hard to hide, malign, and compartmentalize sex, although I will likely never agree with many of the ways they have tried to accomplish this goal. In the ideal, saving sex for marriage means saving sex for a relationship in which both parties, with God’s help, are prepared to sacrifice, compromise, and work for the good of their partner. It’s a lofty goal, and, as with most lofty goals, it has proven almost completely unattainable—a2009 study claimed that 80 percent of young unmarried evangelical adults admitted to having sex. But even after years of anger and questioning, I find this lofty goal very compelling, however difficult it may be.

What we learn through Lee and Grey’s relationship is that both characters have weaknesses and quirks that the other person must know, accept, and even love in order for the relationship to remain balanced. It’s a cliche, but it’s true: good sex requires knowledge, not only self-knowledge, but also knowledge of our partner. It requires vulnerability, tenderness, honesty, and the willingness to try things that make us uncomfortable. It requires that we look at another person and tell them, “Who you are, and what you want, are as important to me as my own pleasure.”

Has that ever happened during a one-night stand? I’ll suspend my disbelief, because I’d like to hear all of your stories. But I’m skeptical. Dismissing the possibility that great sex might require vulnerability, intimacy, and self-sacrifice—commitment, in other words—as “archaic and patriarchal” seems a little bit like throwing the baby out with the bathwater. If anything, it is painful, and we do not like pain.

Ultimately, if great sex scenes are hard to do well, Hollywood isn’t entirely to blame. Our appetite for the sloppy, the cheap, and the fleeting have grown exponentially in proportion to our access to visual stimulation. The industry can get away with flash, glitz, and good lighting rather than giving us any real intimacy; it can get away with rosewater-and-glycerin-smeared actors rather than showing us naked human desire. Why? Because we’re too easy. We’ve chosen to ignore what true intimacy looks like. We’re too quick to believe that true love will cure us of all pain—even the productive kind. We are too willing to trade one Mr. Grey for another.

In the end, it’s intimacy that frees both Lee and Grey from self-loathing. She sees his desire for control, his desire to humiliate and punish, and honors it. He admires and learns the story behind each scar on her body. She says: “…I’ve found someone to feel with, to play with, to love, in a way that feels right for me. I hope he knows that I can see that he suffers, too. And that I want to love him.”

In other words: I see you. I know you. I want you. I love you.