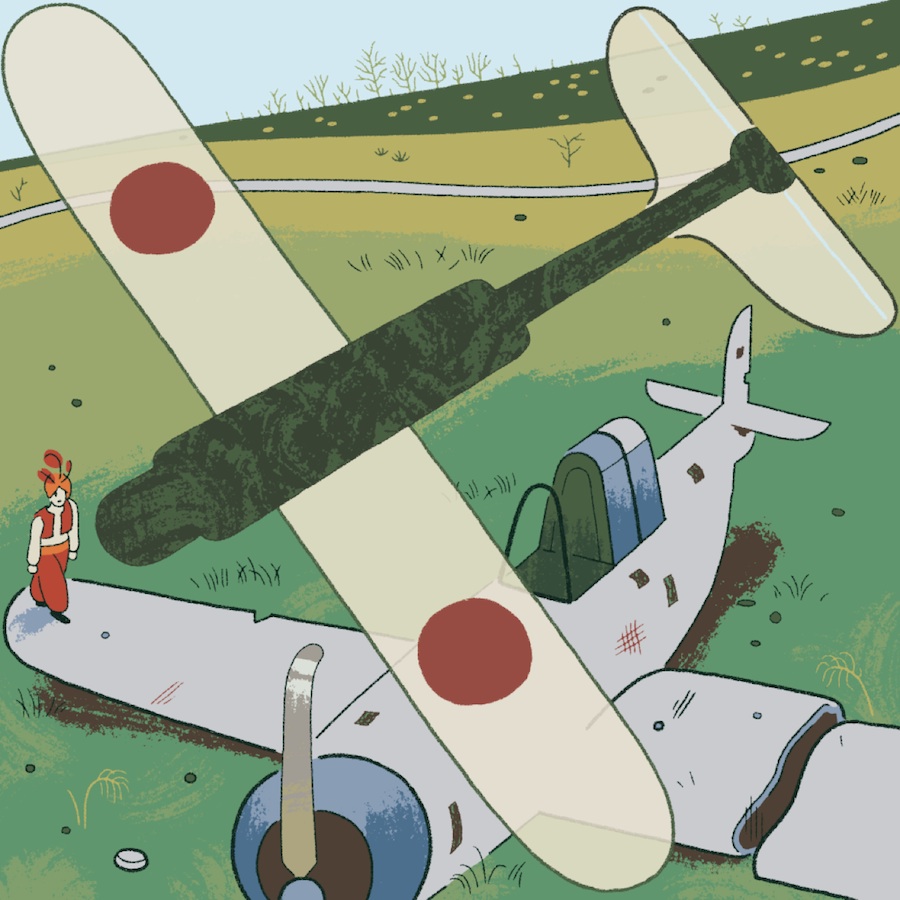

We are pleased to feature an excerpt from the July 2016 edition of online magazine Bright Wall/Dark Room, which is focused on the films of Steven Spielberg. In addition to the essay below by Brian Doan on Spielberg’s “Empire of the Sun,” the edition includes pieces on “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” “Jurassic Park,” and “Schindler's List,” “A.I. Artificial Intelligence,” “Bridge of Spies” and “The Sugarland Express.” Included the edition is a profile on Christian Slater’s career and duality, from “Heathers” through “Mr. Robot,” by pop culture writer Soraya Roberts. The illustration above is by Sophia Foster-Dimino.

You can read previous excerpts from the magazine here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or purchase a copy of their current issue, go here.

“I’m building a man-flying kite and writing a book called Contract Bridge.”

—Jamie, to con-man and scavenger Basie, in “Empire of the Sun”

It was not the Music Box in Chicago, with its gloriously preserved 1929 architecture, where I saw “L’Atalante,” “The Bicycle Thief” and “Jules and Jim” on back-to-back-to-back weekends, and had my cinephilia illuminated. It wasn’t the Masonic Temple, where a live orchestra accompanied the road show of “The Passion of Joan of Arc” in 1997, and Falconetti’s face shined larger than life above my head. And it certainly wasn’t the old State Theater of my childhood, the renovated ‘20s palace in downtown Kalamazoo, where my siblings and I saw all kinds of re-released Disney cartoons with our parents, until it was shut down in 1982.

The UA Theater in Portage, Michigan—located behind the Crossroads Mall that was its own communal temple for local tweens and teens—had none of the charm or historical character of the aforementioned movie houses, but it opened to great fanfare in December of 1987 in my hometown. Because that quirk of timing dovetailed with the maturation of my own movie-going experiences, this state-of-the-‘80s multiplex would be the most important theater I’d ever see films in.

The local Kalamazoo Gazette ran a long piece by its film critic, extolling the new theater’s modern architectural design, improved projection, and rich sound. These were the days when mid-sized city papers could still afford to carry their own critics, and such was the earnestness with which this gentleman did side-by-side comparisons of how “Wall Street,” the then-new Oliver Stone picture, played at the UA versus another local theater, that I still can’t watch Michael Douglas sip on a drink in that film without remembering the writer’s noting of the sharp, clear sound of ice falling into the glass.

I was a 14-year-old budding film buff when the UA opened, and when my Dad and I went to see “Wall Street” that following week, I felt it was important to see it at the new theater, in large part because of that critic’s description. Walking into the glass-and-steel building whose huge, wall-like windows differed so much from the brick boxes of other theaters (making it feel like a greenhouse of cinema), I took in the large “UA” neon sign looming over the main lobby; the large, open airiness of that space combined with the crowds, the light, and movie paraphernalia of posters and cut-out displays to make the whole place feel like a party.

Was the projection actually better? Was the sound actually crisper? Who knows? I was 14 and took that Gazette critic at his word, because it certainly felt better to me. And it was the textured feeling of that space—its ability to take the week’s new films and make a commercial multiplex feel sensuous to my young eyes—that transformed my movie-going.

Two weeks later, the new Steven Spielberg film, “Empire of the Sun,” came to the UA. I’d seen ads for it in Premiere, the new cinema bible that I’d first discovered the previous summer in an airport gift shop, as Dan Aykroyd and Tom Hanks stared out in “Dragnet” gear on its cover. The oversized pages of Premiere acted like the glowing “UA” sign in the theater—their bigness made the publication stand out from the other entertainment magazines on the rack, and enhanced the pictures, the prose, and—especially—the full-page ads for upcoming films that ran in every issue. Premiere didn’t just offer brilliant writing about movies, but felt like a movie, and that was appealing to me, as I transferred my trainspotting tendencies from comic book collecting to a more intense kind of cinema-going. To paraphrase a line from the first movie I ever saw in a theater, I felt like I was taking my first step into a larger world, and here was my new magazine guide, telling me about the latest film from a director whose work—along with that of his pal George Lucas—had colonized my young brain throughout my childhood.

“Empire of the Sun,” Spielberg’s adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s autobiographical novel about his time in a Japanese-run internment camp in China, comes at us less as an argument than as a series of cinematic intensities, nearly all of them centered around movement and escape:

- Young Jim (Christian Bale), the film’s 12-year-old protagonist, separated from his parents, lost in the crush of an evacuating Shanghai crowd, his toy airplane an ironic signifier of identity and flight amidst the suffocating browns and blacks of the clothing that encircles him.

- Jim’s glider flying against the overcast sky of gray-blue and the nearly-empty field of yellow-brown grass, zooming behind its owner like it has a life of its own, while Jim becomes besotted by a downed “Zero” plane, he and the tracking camera circling it in a state of near-hypnosis.

- Jim standing almost at attention, enraptured before the row of Zero fighters, to sparks from the mechanics’ tools bursting off the planes like a child’s vision of fireworks.

- Jim racing through the concentration camp like one of Fagin’s urchins, scavenging for de facto camp Godfather Basie (John Malkovich), creating a game out of deprivation and necessity.

- Jim running to watch the American P-51 mustang attack from the internment camp towers, cheering the planes on, the paradoxes of his various military loyalties washed away in the adrenaline of color, smoke, and light. “P-51!,” he yells, even more delirious with fear and joy than he was when earlier discovered the downed Zero. “Cadillac of the skies!”

These punctuations are almost always ironic, erupting out of moments of entrapment, invasion, the stasis created by fear and uncertainty. For a contrast with Spielberg’s use of open space and sensuous camera movement in these scenes, one might compare the claustrophobic and equally intense control he displays in more static, tightly framed moments; Jim’s initial meeting with Basie, for instance, is mostly a series of tight, shot-reverse-shot close-ups, with Basie’s face concealed by a hat, and the shadows that seem to emanate from his face and shoulders. Or more disturbingly, witness the rush of tones and the confused adolescent face Jim makes later in the internment camp, as he furtively watches the English husband-and-wife with whom he shares barracks space make desperate love, separated from him only by the thinnest scrim, while bombs explode in the skies behind them.

This balance of tones and framings seems an apt signature of this moment in Steven Spielberg’s career—it suggests the difficult place he found himself in, between the ‘child-like’ wonder and giddiness of his early work, and the more ‘mature’ stories and themes that would be fully fleshed out in the decades ahead. “It’s really about the death of innocence, the death of one’s childhood,” he says on the 1987 promotional, “making-of” documentary that accompanied the film. “Which is kind of the opposite of stuff I usually do. I usually celebrate childhood, and I usually celebrate the kind of perseverance and preservation of innocence, but this was a really different story about how it takes an entire war to turn a young boy into a man.”

I put “child-like” and “mature” in single quotation marks above because I wanted to suggest the conventional way the late 1980s are often read in Spielberg’s career, in relation to what came before and after, and how limited that reading of compromise, awkwardness or failure really is.

When “Empire of the Sun” was first released, its reviews were decidedly mixed. Roger Ebert noted its technical skill, but said, “But it never really adds up to anything … Spielberg allows the airplanes, the sun and the magical yearning to get in his way.” Janet Maslin’s review in The New York Times was often glowing, but she complained that “The pattern of events that occur within the camp is at times difficult to follow, in part because the emphasis is divided equally among so many different characters and episodes.” The anonymous reviewer for Variety felt, “John Malkovich’s Basie, an opportunistic King Rat type, keeps threatening to become a fully developed character but never does. Other characters are complete blanks, which severely limits the emotional reverberation of the piece.” Pauline Kael loved its first 45 minutes, but said, “first in brief patches and then in longer ones, his directing goes terribly wrong … Spielberg throws himself into bravura passages, lingers over them trying to give them a poetic obsessiveness, and loses his grasp of the narrative. For the sake of emotion-to have something to say, to give the picture some meaning-he pumps it full of false emotion.”

Spielberg had been given the Irving G. Thalberg award at the previous spring’s Oscars, where he spoke of the importance of story and script, and admitted that his own work had sometimes relied more on the kind of “bravura” style Kael criticized; as Joseph McBride wryly notes in his comprehensive biography on the director, the complaints from some critics about the darkness of the film’s second half “must have seemed strange to a filmmaker who previously had been pilloried by many critics for his supposed sentimentality about childhood.” Standing out from his peers, Andrew Sarris declared “Empire of the Sun” the best film of the year, “a fusion of kinesthetic energy with literary sensibility, pulse-pounding adventure with exquisitely delicate sensitivity.” He would later say that he felt this would be the film Spielberg for which would be remembered.

Spielberg’s previous film, “The Color Purple,” had been an adaptation of a complex and deeply personal novel. It got mixed reviews, but was compensated with eleven Academy Award nominations, was a considerable box office success, and for all the controversy that swirled around the film, is assured a place in Spielberg’s history as his first “grown-up” movie. By contrast, “Empire of the Sun” received just six Oscar nominations (all in technical categories), needed overseas box office to make back its budget, and is often the forgotten member of Spielberg’s de facto “World War II trilogy,” the sidekick to “Saving Private Ryan” and “Schindler’s List.” Taking the longer view of this period of his career, one might argue that the post-“E.T.” run that starts with his dire “Kick The Can” segment from the 1983 “Twilight Zone” movie and ends with the confused, frustrating hodge-podge of “Hook” (1991) (with stops along the way at “Always“—his most disappointing film—and the hit-and-miss “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade“) represents a Difficult Middle Period, an extended, movie-making version of what Billy Bragg once called “the difficult third album.” Having opened with a series of artistic and commercial bangs, how does an artist get through adolescence? And what happens when the audience doesn’t necessarily want you to change?

Despite my own adolescent process of gorging on film histories, biographies, books of criticism, and movie magazines, none of this meta-textual coverage registered with me as I walked into the UA and settled down in my seat to watch the film back in 1987. Like Jim hoarding Basie’s Life magazines in the camp, desperate to be “adult” while still holding on to the toy planes and chocolates of his childhood, I displayed my stores of nerdy movie knowledge like a badge of sophistication, while still holding on to the hope that the new Spielberg movie would unleash the same giddy delight in me that “Raiders of the Lost Ark” and “E.T.” had a few years before. I was fourteen, and therefore clearly all set to take on the world; but I was also a boy who’d grown up in the shadows of movie houses, watching Harrison Ford stride heroically across a variety of fantasy landscapes. In that neither/nor state, I was in for a rude awakening.

My memory of that first viewing calls up sensations of discomfort, confusion, and boredom. Bruising childhood experiences with Carol Reed’s adaptation of “Oliver!”—ubiquitous on TV, and full of such badly-calibrated excess that I still think it’s the worst movie musical ever made—had left a subconscious wariness about Dickensian tales of English childhood deprivation, so I pulled back from an identification with Jim, despite the brilliance of Christian Bale (he was 12, it was his film debut, and the astonishing presence and awareness he shows makes it his best performance). The early patches of the film in Shanghai felt slow-going, while the stuff in the camp felt overly episodic. Once the P-51s liberate the camp, the 25 minutes that follow felt like anti-climactic tedium. There were certainly images I liked—many of the intensities I listed above, especially the bombing scene, certainly registered for me in 1987. But I was too young for the film’s politics, for its complex ironies, for its deep ache about family. I had not then seen “The Color Purple,” so this was my first exposure to the “adult” Spielberg, and it felt awkward and uncertain. Oddly, if the film had been made by another director, or shot in black-and-white like the Classic Hollywood adventure films I was feverishly taping off TV at the time, I probably would have liked it a lot more, even then. But watching your favorite director shift, even as you yourself are doing the same thing, was one shift too many.

To return to Roger Ebert, this quote from his “Great Movies” piece on “La Dolce Vita” feels resonant: “Movies do not change, but their viewers do.” High school came, then college and academic film studies, and two years of repertory houses in Chicago, and graduate school, and thousands of tapes, discs, TCM viewings, movie binges…The film didn’t change, but I changed, and I now stand with Andrew Sarris: “Empire of the Sun” seems self-evidently one of Steven Spielberg’s very best films, outpaced only by the sensational adrenaline rush of “Jaws,” and standing slightly ahead of the Truffautian melancholy bliss of “E.T.” Especially when compared to the more hesitant Spielberg movies that surround it in the Difficult Third Album period, “Empire of the Sun” sings with confidence, and an abiding faith in a youthful perspective that has fueled so many of Spielberg’s best films.

The later stages of Spielberg’s career—the confidence of films like “A.I. Artificial Intelligence,” “Munich,” “Lincoln,” and “Bridge of Spies”—have helped to “normalize” the slower, more contemplative passages of “Empire of the Sun“: The sun and the magical yearning don’t seem to get in the way as much as they might have for critics 30 years ago. In fact, looking at the movie now, it seems apparent that it’s precisely the gangly, uncompromised clash of styles, tones, and plot points so criticized in the late ‘80s that make “‘Empire of the Sun” sing. The film had actually started as a David Lean project that Spielberg was going to produce, until the twin difficulties of adapting Ballard’s novel and finding ways to shoot in China (Spielberg’s was the first Hollywood film to shoot in Shanghai) caused Lean to give up. Spielberg picked up the project, and the film reverberates with a Lean-like faith in both the wonderfully loaded ironies of genre to unlock history, and the power of imagery to express ambiguity, to bring the audience inside the sensations of the framed space, and the characters’ unstated desires.

As the initial response to “Empire of the Sun” suggests, that’s a risky strategy to pursue, especially in the critical atmospheres that surround “prestige production,” where commercial filmmakers are expected to spell out in capital letters what a more art-house sensibility might get away with via allusion. But contra Variety ‘87 and Janet Maslin, the characters of “Empire of the Sun” are not blanks, nor does the episodic structure leave threads dangling—in both cases, Spielberg is simply working out an anecdotal style with a doubled sensibility: we’re always simultaneously in Jim’s perspective (where contradictions of tone or response aren’t a problem, but a survival strategy) and slightly at a distance from it, able to understand before Jim does the flaws of Basie, camp doctor Rawlins (Nigel Havers), and all the other parental figures in whom a scared Jim places his faith. The necessity of this inside/outside perspective to the pathos of the story requires the very energy and “bravura” for which Spielberg was criticized: Jim’s breakdown while watching the P-51s doesn’t work unless we feel his initial glee. “Empire of the Sun” works in ways that “Saving Private Ryan” sometimes doesn’t because Spielberg has the adolescent’s courage to avoid thematic speeches and underlined imagery, choosing instead to place a bet on the “poetic obsessiveness” that Kael found so problematic. With one foot in his stylistic past and one in his future, Spielberg worked on “Empire of the Sun” like Jim simultaneously building a man-flying kite and writing a book called Contract Bridge. It’s a masterpiece of the middle period that Spielberg simply couldn’t have made at any other point in his career.

My own, teenaged sense of movement was still working itself out. Back inside the UA (which would suffer decline over the next 15 years, eventually being replaced by Celebration Cinemas), I hadn’t yet worked out the importance of the sheen Spielberg refused to relinquish. The neon of the lobby and the glossy pages of Premiere were thrilling, but the notion that such things might have more than just a surface-level relationship to being a “grown-up”—that there might actually be a methodology within it—was a transformative lesson of adulthood that lay ahead, visible through the UA’s oversized windows, and caught in the hypnotic tailwind of a glider.