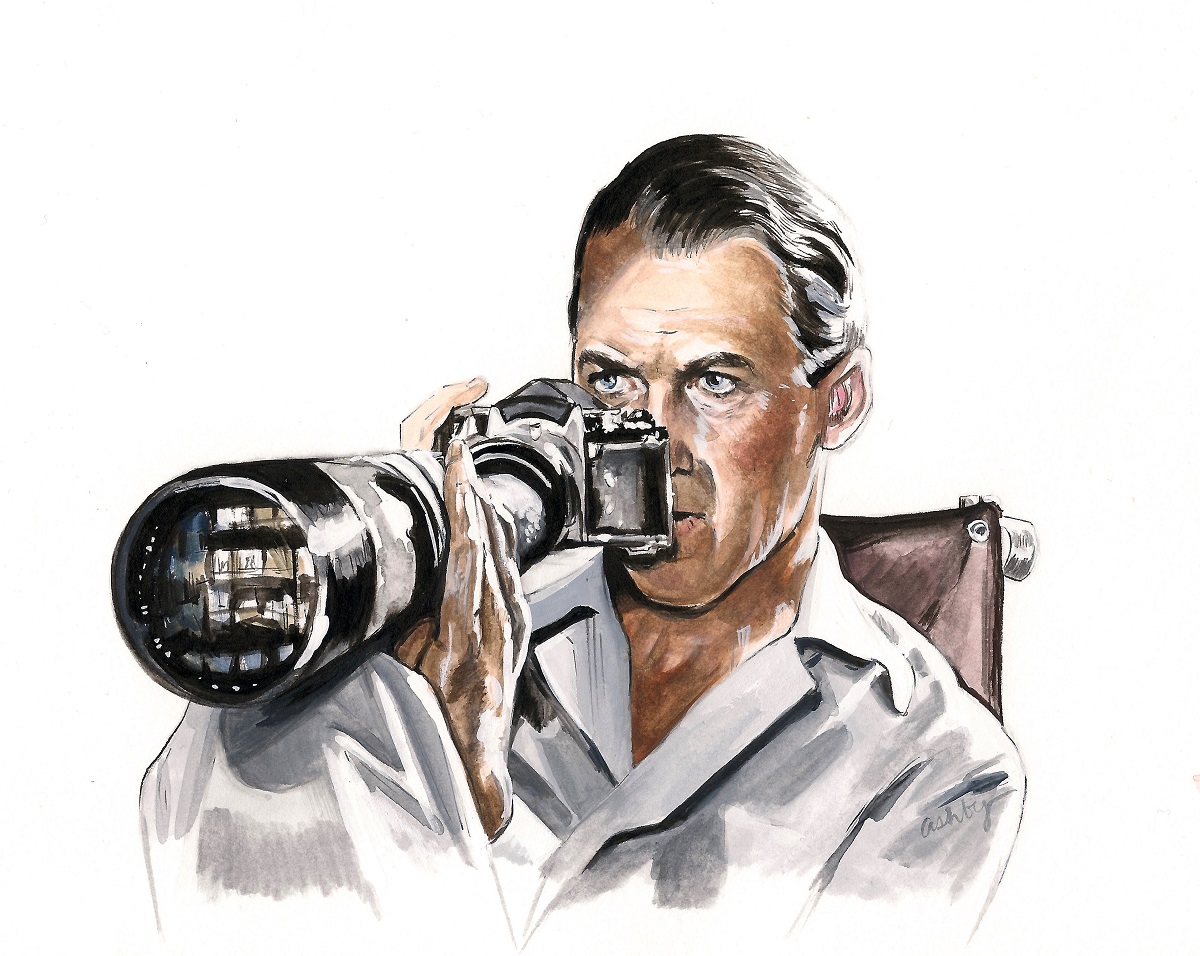

The great writers at “Bright Wall/Dark Room” have released their July 2015 issue, entitled, “Summer,” which includes the following piece by Kelsey Ford on “Rear Window.” In addition, the issue also features essays on “Do the Right Thing,” “The Seven Year Itch,” “Stray Dog“ (Kurosawa version, not the new one), “The Sandlot,” “The Goonies,” “Adventureland,” “Wet Hot American Summer,” “Dirty Dancing“ and “Dazed & Confused.” Read more excerpts here and you can buy the magazine on your iPhone and iPad here, or sign up for the web-based online version here. The illustration above is by Brianna Ashby.

It’s nighttime in New York. Humid air gives way

to rain. A couple, sleeping on the fire escape, is forced to drag their

mattress back inside. A man in a wet parka leaves his apartment with a

suitcase. An intoxicated songwriter swipes at the paper music laid out on his

piano. The man with the suitcase returns, and then leaves again. A woman,

dressed up and returning from a long night, shoves the door in her date’s face.

The man with the suitcase returns.

Some floors up, L.B. Jeffries (James Stewart)

is watching. He’s confined to his wheelchair with a broken leg, and the

restlessness of being a sidelined photographer has gotten the best of him.

During the day, he has a nurse, Stella (Thelma Ritter), and a fiancée, Lisa

(Grace Kelly), to keep him company. But now it’s nighttime. He’s alone and he

can’t sleep.

The courtyard his apartment window looks out on

is a standard one, with a range of buildings: some tall and narrow and brick,

others short and squat with more windows than square footage. Ladders on fire

escapes lead to small gardens below. Each window offers miniature dramas: the

heartbreak, the happiness, the loneliness, the mess. Jeffries’ vantage is

perfect: from above, he can see without being seen.

When others should be dreaming, Jeffries is

watching those who aren’t.

*

My first summer in New York was filled with

fever dreams. I didn’t have an air-conditioner and the humidity laid itself

thick. I waitressed at a bar most nights until three in the morning, went home

to pass out in a soggy heap, only to wake up hours later, still inside a dream

and sure I was somewhere I shouldn’t be. I’d hear voices in the other room,

maybe the sound of a jukebox, as if I was still in the bar or in a bookstore or

anywhere else except for in my apartment, alone. I’d panic and grab at a pair

of jeans and pull them on, even as I repeated to myself: this isn’t real, this is a dream, you’re imagining this, you’re still dreaming.

I’d believe it wasn’t real, but I also wouldn’t. The majority of mornings, I

woke up still wearing those jeans.

That feeling wouldn’t leave for the rest of the

day. It hung on me, that fear of being stuck somewhere between here and there,

consciousness and unconsciousness. My life took on the tenor of the uncanny. I

couldn’t differentiate between reality and dream, logic and feeling. Exhaustion

and heat got the better of me.

This wasn’t the first time I’d experienced

this, but it was the first time I had as an adult. Growing up, I was convinced

we’d had a dog we never had. It was years before my mom realized, and quickly

debunked, what I considered a very real memory.

Another time, I dreamt I was at a ski lodge

with my family. We were eating lunch, still wearing our gear and boots. I excused

myself to go to the bathroom. In the hallway, I passed a boy a few years older

than me, huddled next to an ATM while his wrist gushed blood. We made eye

contact. I kept walking. No one else was stopping, so I didn’t either, and he continued

bleeding. Even now, the only way I’m sure this was a dream is because there’s

no way it could possibly be real. It’s too horrific and strange.

It’s a particular kind of writerly trait, to

let dreams bleed into day, but these moments were visceral and dangerous. They

clung to me, so that even if they weren’t real, their affect was. That particular

summer, New York’s persistent heat broke down the slim separation between

fiction and truth.

*

L.B. Jeffries stays in that small patch next to

the window, a camera within reach, and watches his neighbors. He picks at the

bare bones of their stories and assigns them meaning: Miss Lonelyhearts, the

middle-aged woman cooking elaborate dinners for one and crying over her empty

plate; Miss Torso, the scantily clad dancer entertaining a roomful of men;

Songwriter, the man with a piano who is, Jeffries surmises, fresh out of an

unhappy marriage.

The hollows of his neighbors’ lives are made

all the more apparent beneath the bareness of summer heat. Remaining clothed

and concealed is unbearable. It’s easier to keep skin unburdened, windows open,

your life there for thesurrounding

world to see.

Stella side-eyes Jeffries’ persistent

surveillance. She chides him: “I can smell trouble right in this apartment. You

broke your leg. You look out the window. You see things you shouldn’t.

Trouble.”

Jeffries fixates on a husband and wife a few

floors down and across the way. He only sees slices of their story, but is sure

he knows how to knit them together: an unhappy husband with a short temper, a sick

but somehow missing wife, those strange comings and goings in the middle of

that rainy night.

This is enough for Jeffries to become sure that

the husband killed the wife.

Jeffries calls his friend on the police force,

but the detective doesn’t buy it. “That’s a secret and private world out

there,” he says. “People do a lot of things in private that they can’t do in

public.” But what the detective isn’t acknowledging is the city’s two way

street when it comes to voyeurism. You feel justified, watching neighbors

across the courtyard, because they’ve left their blinds up. But when you’ve

left your own blinds up, you’re all too aware of the potential exhibition. You

know anyone can see, and yet you still perform.

The husband’s blinds are up, and he does little

to deter the growing narrative. He has shifty eyes. The wife’s purse is still

in the apartment, and why is he tightening up a trunk so firmly? Why is he keeping

such strange hours?

Lisa is a reluctant participant at first. She

corrects his assumptions about Miss Torso. When Jeffries thinks Miss Torso is

spreading herself thin with so many men, Lisa shakes her head. No, Miss Torso

doesn’t love any of them. “I’d say she’s doing a woman’s hardest job: juggling

wolves.” When their attentions shift to Miss Lonelyhearts, Lisa calls her quiet

actions a kind of “manless melancholia.”

But not until she sees the wife’s abandoned

purse, does Lisa allow that Jeffries may be right. She says that “women aren’t

that unpredictable.” They don’t leave their purses behind. Anywhere they go,

they take their “basic equipment.” It doesn’t add up.

She keeps Jeffries company while they keep

watch, hoping to point at some proof that will change the police detective’s mind.

In a quiet moment, Lisa turns the narrative labeling around on the pair of them.

“You’re not up on your private eye literature,”

she says. “When they’re in trouble, it’s always their Girl Friday who gets them

out of it.”

Here, Jeffries is the intrepid gumshoe and Lisa

is Jeff’s Girl Friday.

The idea makes Jeffries scoff. And this,

perhaps, is why Jeffries is so insistent on looking out. He doesn’t want to

look in. No matter his feelings for Lisa, or her feelings for him, he’s sure

they’re not a good fit. She couldn’t possibly live the life of a photographer’s

wife. Jeff says he needs “a woman who’ll go anywhere, do anything, and love

it.” As much as Lisa insists she’s capable of whatever lifestyle Jeffries

throws at her, he won’t listen. Lisa is telling him one story––that she loves

him, and he’s wrong to protest––and he’s telling her another.

Rear

Window is a movie about the stories

we choose to tell.

*

As a waitress at a small sports bar with very

few clientele, I’d spend my nights watching others. Lads got drunk on Guinness

and traded turns on Big Buck Hunter. New couples leaned into each other’s

shoulders over buckets of French fries. An old man with a cane came in every

night at 8 p.m. for a greyhound and a glass of cranberry juice. Actors got

trashed off whiskey and performed soliloquies.

It was all very loud, and all very much about

everyone else. So late one night, one of the few nights I had for myself, while

out with a friend and a few drinks in, I decided we should go to a psychic. A

very rational and sane idea. I found a name on Yelp, called the number, and an

hour later, we were huddled in her hot stairwell, waiting for our turn.

The psychic worked out of her apartment’s small

entryway. A short table with a cheap, gold cloth thrown over top was pushed

against the wall, next to a door with a thin veil down it. I could look through

and see her fridge, with photos stuck with magnets and boxes of tea piled on

top. She handed me the stack of tarot cards, asked me to cut it, and then told

me to keep a question in mind as she read.

I can’t remember what I asked, but I remember

my intent.

The reading was rhythmic. The card, flipped.

The card, interpreted. An occasional glance to gauge my reaction. She told me I

was sensitive and quiet but emotional. She said I’d be going to court in the

next year, but it would come out in my favor. She said I’d have more

responsibility at work and no free time. She said my luck in love is zero but I

have a good energy and would be successful. She told me not to settle until I

found a home next to the ocean.

The reading was expensive and useless, but I

still scribbled her words on the back of a receipt and kept it in my wallet,

where it stayed for months. I wanted someone on the outside looking in to tell

me what they saw, and I wanted to believe some version of it was truth.

*

Because Rear

Window is a movie, the story Jeffries thinks he sees, turns out to be true.

Because Rear Window is a movie

directed by Alfred Hitchcock, it’s a story about murder.

So much ofthis movie mirrors a different aspect of itself. The way the film was shot

on one stage mirrors Jeffries confinement to his apartment. Jeffries’

observation of his neighbors mirrors our observation of him. But this breaks in

the final act, when Lisa decides to shift their role from passive to active

observers.

In order to disprove one story Jeffries is

telling (that he and Lisa aren’t a good match), Lisa takes it upon herself to

prove the other one. She is a woman that can go anywhere, do anything, and love

it. He just has to see this.

Lisa goes across the courtyard and into the

apartment, trying to find the wife’s wedding ring, because no woman would leave

that behind if she weren’t dead. Jeffries remains in his apartment. We stay

with him while he watches Lisa. He sees the husband come home while Lisa is

still inside. All he can do––and we, alongside him––is call the police. But

that final, shaky barrier between audience and performer is broken when the

husband turns and, finally, looks up.

The stories tangle, no longer passive. The

barrier between what might be and what is breaks. That Jeffries survives a near

assault from this wife murderer is not the point of the next scene. The point

is his ownership over a narrative that isn’t his, and the danger that brash

sureness got him in.

He may have been right, but how much did he

almost lose?

*

I bought an air-conditioner and my dreams

stopped dragging themselves behind me like extra limbs. The receipt with the

psychic’s predictions got lost on some late night in some bar. I tattooed a

blue whale the size of a thumb to my right rib. My life settled. I tried, and

often failed, to stop relying on easy narrative. I listened to my bones. I quit

waitressing.

Rear

Window finds a similar peace in the

end. Characters from different stories (figuratively and literally) end up

together. Miss Lonelyhearts and Songwriter assuage each other’s loneliness. The

man Miss Torso truly loves comes home in uniform. And Jeffries and Lisa settle

into the reality of each other.

Summer in New York is so many stories at once.

Mini-symphonies filled with potential. It’s a love story. It’s a murder in a

courtyard. It’s the tattoo artist around the corner and the whiskey sour you drink

at dusk. It’s late nights and fever dreams. It’s a husband at the end of his

rope and a girl trying to prove to the man she loves that she’s worthy.

It’s heat and soft nights filled with rain.