If you have ever been lucky enough to see “A Christmas Story,” you will understand what I mean when I say “The Sandlot” is a summertime version of the same vision. Both movies are about gawky young adolescents trapped in a world they never made and doing their best to fit in while beset with the most amazing vicissitudes.

Neither movie has any connection with the humdrum reality of the boring real world; both tap directly into a vein of nostalgia and memory that makes reality seem puny by comparison.

“The Sandlot” takes place in a small American town in the early 1960s. A new boy named Scott (Tom Guiry) arrives in the neighborhood and desperately wants to fit in. There is a local sandlot team with eight players, and so he could be the ninth – if only he could play baseball! He cannot. He’s so out of it, he doesn’t even know who Babe Ruth was. He asks his stepfather to teach him to play catch (there is a quiet poignancy in being asked to be taught such a thing), and his stepdad agrees, but puts it off, and then one day Scotty finds himself, to his horror, on the sandlot in left center field with a fly ball descending on his head, which it bounces off of.

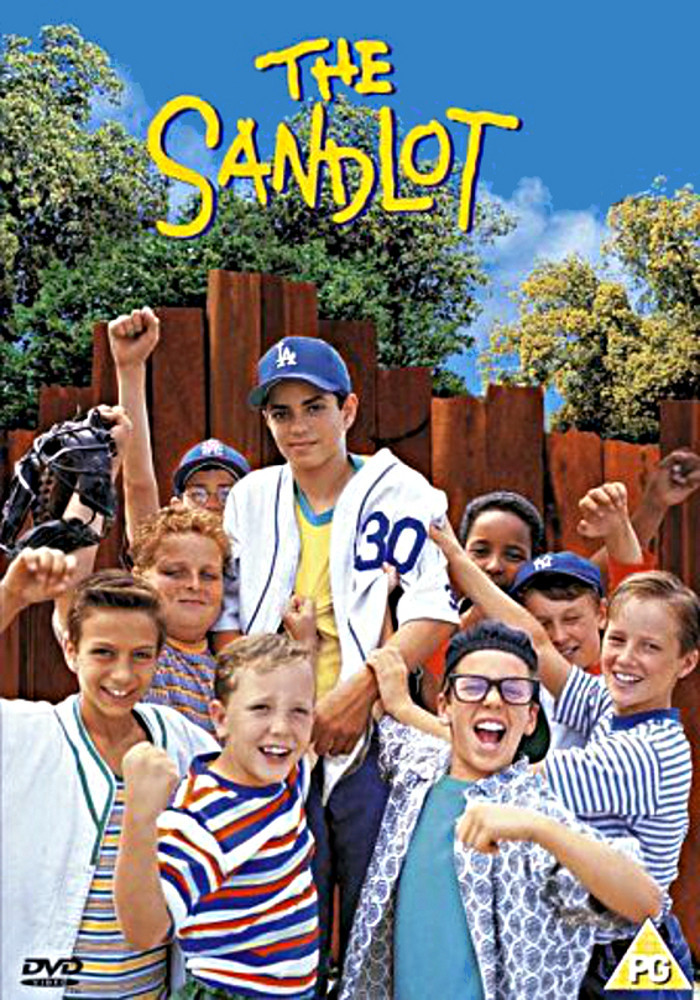

That would be the end of his baseball career, were it not for the understanding of Benjamin Franklin Rodriguez, the best of the players, who tactfully teaches Scotty what he needs to know, thus launching the finest summer of his young life.

It is one of those summers that are hot and dusty, and the boys play baseball every day, and sometimes go to the municipal swimming pool, where they lust after the impossible vision of the beautiful lifeguard in the red swimming suit. Lust is balanced by terrors: Behind the wall at the end of their sandlot is a backyard inhabited by the Beast, a dog so large and savage that it has become a neighborhood legend. We catch glimpses of parts of it from time to time – a massive paw, slavering jowls – and from what we can see, it’s about as large as a dinosaur.

One day the boys’ last ball goes over the fence into the domain of the Beast. Scotty saves the day. He runs home and borrows his stepfather’s ball, which happens to have been autographed by Babe Ruth, a name that means nothing to him until this ball, too, is slammed over the fence, and then the other players explain to him why his stepfather is not going to be overjoyed to learn that his trophy has become the Beast’s lunch.

All of these events are told in an original, quirky, off-center, deliberately exaggerated way. This is not your standard movie about kids and baseball. It’s so unconventional, it doesn’t even end with the sandlot team winning the Big Game. This movie doesn’t even have a Big Game. (The one game they play is a pushover.) The movie isn’t about winning and losing, it’s about growing up and facing your fears, and as the kids try one goofy plan after another to get the ball back, the story gently leaves the realm of the possible and ventures into the exaggerations common to all childhood legends.

The movie’s director is David Mickey Evans, who wrote the script with Robert Gunter. Their tone and the voice-over narration remind me of Jean Shepherd’s memories of growing up in northern Indiana.

Memories are sharper, colors are brighter, events are more important, and a life can be changed forever in the course of a sunny afternoon.

These days too many children’s movies are infected by the virus of Winning, as if kids are nothing more than underage pro athletes, and the values of Vince Lombardi prevail: It’s not how you play the game, but whether you win or lose. This is a movie that breaks with that tradition, that allows its kids to be kids, that shows them in the insular world of imagination and dreaming that children create entirely apart from adult domains and values. There was a moment in the film when Rodriguez hit a line drive directly at the pitcher’s mound, and I ducked and held up my mitt, and then I realized I didn’t have a mitt, and it was then I also realized how completely this movie had seduced me with its memories of what really matters when you are 12.