Despite the fact that his work has garnered spectacular hosannas from American and British film critics since the 1970s, Éric Rohmer remains, I believe, a largely misunderstood filmmaker in the English-speaking world. In his 1995 book “Flickers,” the astute Gilbert Adair cocked a snoot at a “typical chorus of satisfied [Rohmer] customers: ‘Such a civilized director…’ and ‘Such intelligent characters…’ and, especially, ‘What a pleasure to hear such good talk in the cinema…’” “Aside from the fact that equating a film’s intelligence with the intelligence of its spoken dialogue is to beg a number of crucial questions,” Adair continues, “I would suggest, finally, that Rohmer’s characters are not only among the most foolish, ineffectual, and pathetic milquetoasts ever to have graced a cinema screen, but that, on a generous estimate, ninety percent of the talk is sheer, unadulterated twaddle.”

This is maybe going a little too far but that was Adair for you. A key point in that passage is the implication that Rohmer’s films are better listened too—or, in the case of the non-French speaking viewer, read in the subtitles—than actually watched. That his films, which he largely grouped—“Six Moral Tales, “Comedies and Proverbs,” and “Tales of the Four Seasons”—are talky and perhaps even pedagogical narratives in which mise-en-scene plays only a secondary, or even peripheral role.

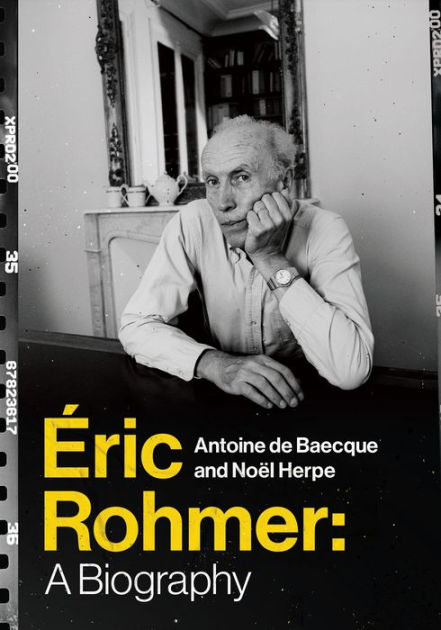

“Éric Rohmer: A Biography” by French critics and film historians Antoine de Baecque and Nöel Herpe, now available in an English translation in a doorstop-thick edition from Columbia University Press is both a remarkably absorbing life story and a valuable critical tool. The life story is absorbing because it’s so unusual. Rohmer did not live the way other filmmakers lived. Not just other filmmakers of the French New Wave, of which he was both a kind of father figure and crucial component. I mean pretty much all other filmmakers. Born Maurice Scherer in 1920, the tall, shy, erudite man, who was shamed by his failure to shine as a potential academic in his early manhood, adopted several pseudonyms under which he began a career as a fiction writer and later a film critic. The final pseudonym, which stuck (although he’d work under at least one more later in his career) was a sly nod to pulp writer Sax Rohmer, although the authors of this book can’t verify that Rohmer was an actual fan and given his tastes it doesn’t seem likely. The salient point here is that for all of his life Rohmer never let on to his own mother that he was a film critic and then a filmmaker, even after the international sensation of 1969’s “My Night At Maud’s.” Similarly, it was only on Rohmer’s deathbed that one of his closest assistants actually met Rohmer’s wife and two sons. The man had a genius for many things, and compartmentalization was one.

The book also explores, in a deep and slightly disturbing way, Rohmer’s methods of building a scenario, which involved building characters from the actual lives and words of the performers he picked for a specific film. In the heated time after the making of Jacques Rivette’s “Out: 1,” the actor Jean-Pierre Leaud called Rivette “vampiric;” a less charitable critic of Rohmer could, citing evidence from this book, use the same word against Rohmer. (Although the fact that, with one crucial exception, pretty much all of Rohmer’s performers revered him might make the argument a hard sell.)

Some have expressed surprise to learn, via this work, that Rohmer was in many respects politically conservative (“I don’t know if I am the Right,” he said in a 1968 interview—1968!—“but in any case, one thing is certain: I’m not on the Left”) and the book does chronicle the criticism his films faced in the later portion of his career for focusing on white middle-class French folk of the provinces. It cites, from Rohmer’s own early critical writing, an account of Murnau and Flaherty’s “Tabu” that praises its making, by Rohmer’s lights, Europeans out of its South Seas characters. And it chronicles Rohmer’s lifelong friendship with notorious French reactionary Jean Parvulesco. The authors retain their equanimity all the while.

Although rendered in a clear, straightforward style, the book is not undemanding. Rohmer’s thought and work were complex, and it’s this fact in part that determines the book’s form, which follows the chronology of Rohmer’s life but also concentrates, in particular chapters on specific modes of activity or thought, and here the authors will hopscotch around the timeline to serve the larger thematic concerns. The book also, as is only fit, treats Rohmer as a French artist, one working within several French traditions, and the reader conversant with those traditions will have an easier time with the book, specifically when a passage like this one comes up: “In the end, ‘Loup, y es-tu?’ started looking like a play by Feydeau, with its cuckolding and mistaken identities, with its sexcapades that people try to minimize by lying. But it is a Feydeau that dreams of Marivaux or Racine.”

Where the book really shines is in constructing a through-line of Rohmer’s aesthetic and its consistency from theory to practice. The authors quote generously from Rohmer’s critical work and locate key tenets from the very beginning. “In contrast to graphic, purely visual expression, cinema makes use of the means that are specific to it and creates meaning when it moves about objects or bodies within the space of the frame and a flat surface, in accord with an organization inspired by nature,” de Baecque and Herpe comment when citing Rohmer’s very first published critical essay, “Le cinema, art de la espace.” from 1948. Cut to twenty years later, and the making of “My Night At Maud’s.” Preparing the room of the title character, Rohmer “spent hours placing this or that object” on the set. “One fine day, [lead actor Jean-Louis] Trintignant openly criticized Rohmer for paying less attention to him than to the ashtrays. To which the filmmaker replied ‘I’m less worried about you than about the ashtrays.’” The recounting of the shoots and the examination of the results eventually demolishes the idea of Rohmer as a paragon of talky semi-humanist cinema and assists in an appreciation of him as a sublime aesthete whose works are exquisitely crafted critiques of human vanity. Their moral value lies not in the lessons they may or may not impart, but in their perfection of form. This is more immediately evident in a literary adaptation such as his sublime 1976 “The Marquise of O…” but it holds for every one of his films. The pursuit of this ideal resulted in a body of work that makes him as crucial a figure of cinema as his ideal, F.W. Murnau. This book is, among other things, a provocative and reliable companion piece to the work.

“Éric Rohmer: A Biography” is now available. Click here to get your copy.