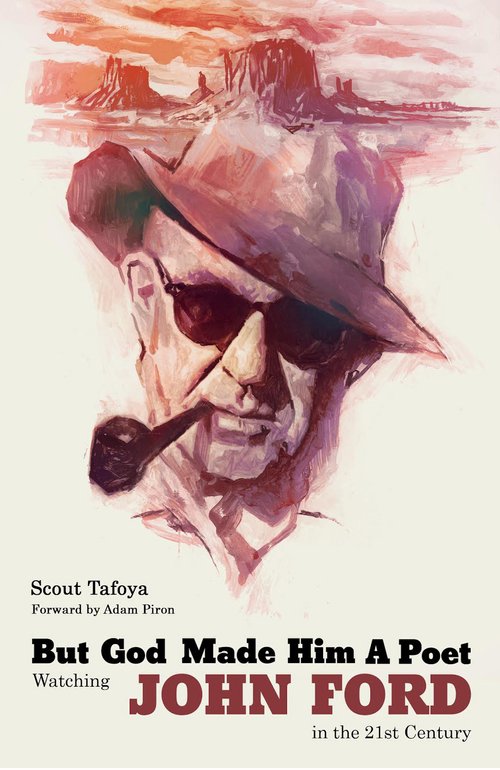

The following is an excerpt from “But God Made Him A Poet: Watching John Ford in the 21st Century” by Scout Tafoya, specifically the chapter on 1940’s “How Green Was My Valley.” Click here to order your copy of the book.

There’s a beautiful empathy to this period in Ford’s career, and not simply in his finally making movies with a defensible value system from a historical long view. He had taken to opening his movies with the name of the author of the source text above the title. “Richard Llewellyn’s How Green Was My Valley” is the opening title card. Like Ford was merely a conduit, a narrator passing on the memories found in Llewellyn’s book. The author was clear enough and Ford himself made no great claims for his own memories in his work beyond the types he appreciated (men and women, one might presume, that reminded him of the better parts of his childhood – hence his keeping his brother Francis around for as long as he could). “How Green Was My Valley” is a rapturous accounting of the highs and lows of a young man’s understanding, as much Proust as any other author, a lot of it is the childhood Ford wished he had had and a little of the one he did. Ford was always talking around his own experience, very rarely addressing it directly, as if he was afraid of what he’d find if he stared straight on. The name above the title absolved Ford, in some ways, of whatever followed. This film beat “Citizen Kane” for best picture, which is just as well. Orson Welles’ reputation as the least appreciated man in Hollywood starts there. He was an art punk. Ford was Hollywood’s brusque, distant, alcoholic father figure.

Master Roddy McDowell, as he’s credited, plays the youngest observer in the valley, the one who witnesses the births and deaths and loves and marriages and betrayals. The film is one of the near-musicals of which Ford was so fond. Song was one of the few languages that can communicate like the moving image, and he knew it could say things a spoken sentence couldn’t. Two people harmonizing at a wedding reception marks them as kindred spirits when class seems to separate them. This collection of parties, buttressed by funerals, is what Michael Cimino was invoking when he made “The Deer Hunter” (with a little “Liberty Valance” for good measure). It’s got the hazy stream-of-consciousness of Virginia Woolf, even if the compositions (especially of the mine where the men of this little hamlet toil) are pure Eisenstein. Sara Algood delivers a rousing speech in defense of husband Donald Crisp in a raging fake snowstorm and it’s like we’re in “Potemkin”, watching the working class rail at the dying of the light. Clarity and dreaminess hand in hand, like the best of cinema. Terence Davies has greater affection for the technicolor musicals and iron jawed melodramas, but he’s born here, with the wash of montage and the martinets at the head of every table. The narration, voiced by Ford’s one-time RKO stablemate Irving Pichel, keeps the film from touching the ground. The miners union is the great battle at the heart of the story. Socialism is a four letter word to some of the old timers. You can still hear Zanuck sweating over the front-facing labor content in Grapes of Wrath.

“Unions are the work of the devil!” cries the local hunchback zealot. Zanuck wanted this to be his next Gone With The Wind, hired William Wyler to direct it and all (whom we can’t seem to escape as a point of comparison; he was a few years away from “The Best Years of Our Lives”, which would do for Goldwyn what Ford did for Zanuck here – give him so much awards gold he’d lose a day polishing it all). Wyler ducked out at the last second leaving Ford a cast that included his newest good-luck charm Maureen O’Hara. Ford was better suited to the material – he also called Philip Dunne’s script “perfect.” Dunne hated the book on which it was based, which may explain why this came out like a half-remembered fantasia and not a story of a minor miner’s sexual awakening. Roddy McDowell’s sexlessness here would haunt him forever; he’d never ever play a credible threat to anyone’s virtue on screen, a sort of British Anthony Perkins. He’d later direct “Tam-Lin”, one of the greatest of the English folk horror films, which you might call “How Grey Was My Valley”. Ian McShane’s the McDowell stand-in in that, and in lieu of beautiful Welsh countryside, he’s got Ava Gardner to marvel at. A lateral move, at the very least. The film is about the difference between theoretical positions and the reality between us and them. The four grown Gwilym boys leave home when their father won’t support the miner’s strike but return home when it’s settled. O’Hara is less lucky. She loves Walter Pidgeon the preacher but has to settle for the mine owner’s son, Marten Lamont. The whole town knows there’s no love there and don’t sing for her nuptials until the rich father (Lionel Pape) demands it. Everyone talks tall about leaving town but the only way anyone seems to is in a pine box. The howl of the whistle always promises more and more loss, more harrowing sights for every would-be widow in town. The Gwylims lose more than their fair share down the mine. The soundless delivery of the news to Anna Lee is one of Ford’s most striking sequences. The sea of depressed coal-stained workers drifting by as on the right of the frame is the desolate sight of loss. Lee stumbles back to the clean house and collapses in the doorway. The world cares not.