Monsters are ubiquitous in the work of Bong Joon-ho. Sometimes they’re literal—a giant, mutated fish comes crawling out of the Han River in “The Host” (2006), and a genetically engineered super-pig takes center stage in “Okja” (2017 —but more often, they’re not so easy to spot, partially because they’re hiding in broad daylight. Bong’s protagonists are just as capable of monstrous deeds as his ostensible villains (his first movie, 2000’s “Barking Dogs Never Bite,” centers on a man killing the dogs in his apartment complex because he can’t stand their barking), and they’re not neatly pigeonholed into antihero narratives that explain them away. He loves his monsters too much to be so cruel.

This is clearest in Bong’s treatment of his more obvious monsters. The creature in “The Host” is a byproduct of human carelessness, and its habit of eating people isn’t outright malice so much as it is simply doing what it needs to in order to survive. And when the super-pig Okja becomes violent, it’s because her extenuating circumstances have taught her to. It’s telling that Mija (the little girl who calls herself Okja’s sister, played by Ahn Seo-hyun) can immediately sense this; even with Okja’s teeth in her arm, she stops ALF leader Jay (Paul Dano) from striking the pig and waits for her to regain her senses, instead. Though Okja is the “monster,” she’s more like a walking Rorschach test; when the characters in Okja look at her, what they see is revealing. Mija sees her sister, Jay sees a larger cause, and the Mirando Corporation sees meat.

In this sense, Bong’s monsters are means towards the end of subverting the audience’s expectations of the human characters. They illuminate the more “monstrous” qualities in the people the audience is supposed to be rooting for. What’s most remarkable is that he does this without damning any of them one way or the other. For instance, the characters of “Snowpiercer” (2013) are made monsters by their environs, a train bearing the last remnants of humanity and splitting them in social classes by which car they reside in. Each car adapts to survive. Some become complicit in a system that exploits children, some choose to adopt ignorance, others turn to cannibalism.

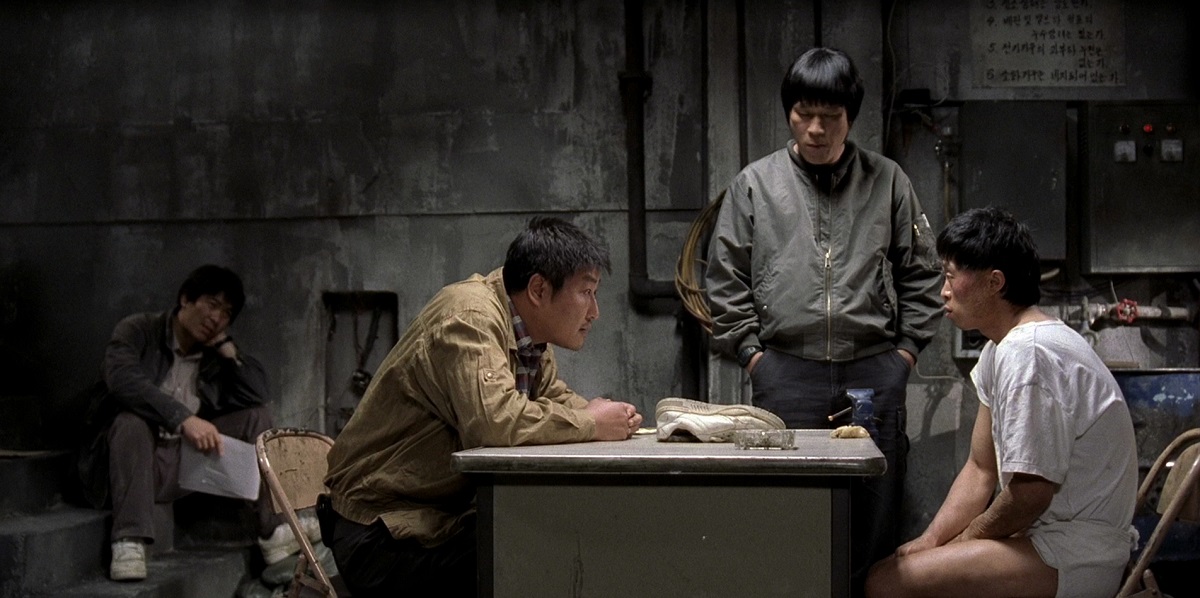

In “Memories of Murder” (2003), which follows an investigation into a small-town serial killer, we see the three detectives on the case struggle until they nearly commit a murder, themselves. The moment provokes horror but it conjures something like heartbreak, too; each failure in the investigation has made them less and less certain of what had once been incontrovertible, and they’ve reached a breaking point. When faced with the evidence that that killer isn’t who he thought it was, Tae-yoon (Kim Sang-kyung), whose mantra had been “the documents don’t lie,” casts the damning papers into the mud.

“Mother” (2009) drives the point home even further, as it starts with duress rather than building up to it. When Do-joon (Won Bin) is arrested for murder, his mother (Kim Hye-ja) begins a mission to prove him innocent. There’s no real antagonist in the movie—there’s no creature, there’s no serial killer, there’s no evil corporation. The monster, looming even larger than the possibility of miscarriage of justice or the suspicion of guilt, is the mother herself. We want her to succeed in clearing her son’s name, but the cost at which it seems to be coming is almost impossible to reckon with. What makes the film wrenching isn’t her descent—we already know that a mother’s love is inexorable—but her own cognizance of it. “Memories of Murder”’s mirror is the killer; “Okja”’s mirror is the super-pig; “Mother”’s mirror is the title character.

This fascination with monsters informs the entire body of Bong Joon-ho’s work. His trademark drastic tonal shifts (“Memories of Murder” has its share of slapstick comedy before descending into utter darkness; “The Host”’s monster madness gives way to a study of grief; “Okja” begins in the idyllic mode of girl-and-her-pig prior to shuttling its audience to the slaughterhouse) shouldn’t work, let alone as well as they do, but they mesh perfectly with the way that Bong refuses to define his characters in black and white. Sadness isn’t always extricable from joy; good often comes with bad. Similarly, this complexity can also be found in the constant presence of more political themes in his work, with government ineptitude factoring heavily into “The Host” and “Memories of Murder” (specifically with regards to South Korean and American relations in the former, and the fight for democracy in the latter), and a broader commentary on consumerism playing into “Okja.”

To wit, the endings of his movies are rarely tidy. The serial killer in “Memories of Murder” remains at large; “Okja” is rescued from the Mirando Corporation, but that’s just one pig among countless others that will still be turned into sausages, not to mention the fact that Mija still eats meat. They reflect the messy reality that they’re meant to portray, and to do anything else would be a betrayal. The key is that monstrousness isn’t a curse so much as it is a sign of being human. It never comes from a place of malice, and triumph—in whatever capacity it is within reach—demands the exercise of empathy and kindness. Bong Joon-ho loves monsters. His films ask that we love them too.