In 1975, Indian cinema released one of its greatest films, Ramesh Sippy’s “Sholay.” For this young grade-schooler, watching it with my parents in Chicago’s Arie Crown theater, it was among the most captivating movie experiences of my life. Fifty years later, I’m sure every South Asian man of my generation still remembers “Sholay” with the most fondness.

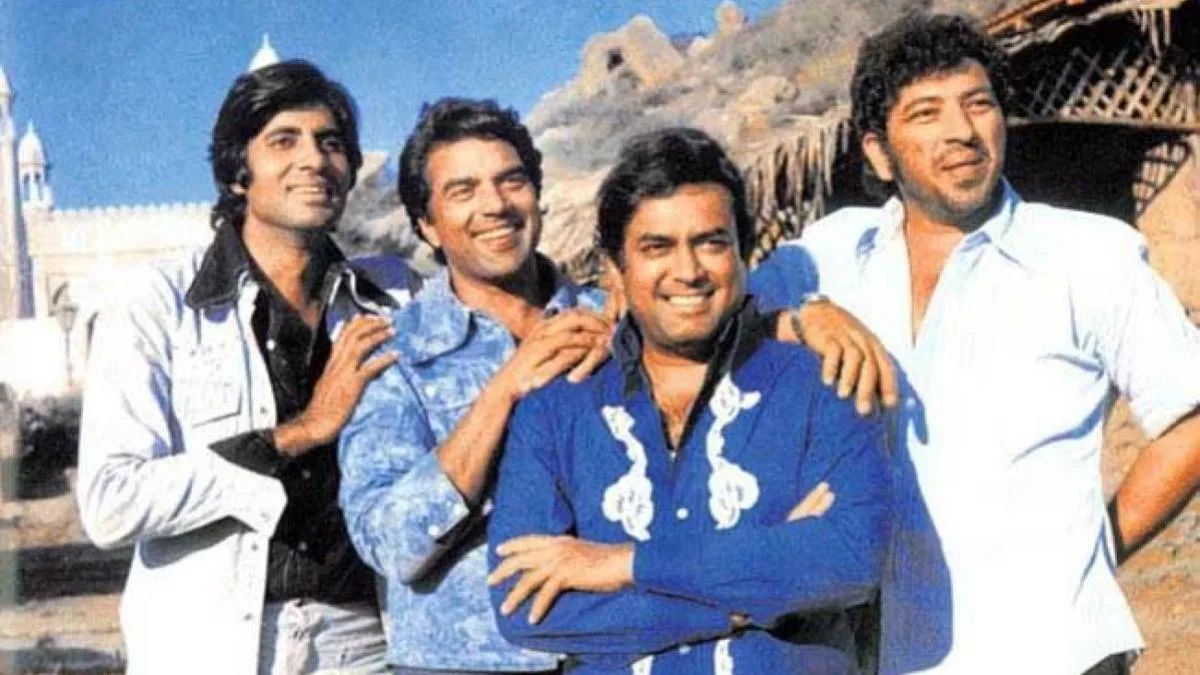

A local officer, Inspector Thakur Baldev Singh (Sanjeev Kumar), hires two small-time convicts, Jai (Amitabh Bachchan) and Veeru (Dharmendra), to capture the renegade scoundrel Gabbar Singh (Amjad Khan). Thakur saw them not only as punks with a moral compass, but crafty enough to outwit Gabbar. In the process, both men fall in love with local women: Jai admires the quiet widow Radha (Jaya Bhaduri, later Bachchan) at first sight, and Veeru consumes himself with the vocal Basanti (Hima Malini)—the two fall into a series of smaller adventures until crossing paths with the final boss. Gabbar Singh may have been among the sadistic villains (pontificating in gruff Hindi, amputating his victims, cackling while killing his own henchmen) that Bollywood audiences had yet seen. The film ends with a twist and a tragedy that would teach young boys to cry.

Overtly, the film is a Western, written and produced not long after the rise of the Italian Spaghetti Westerns, taking inspiration from “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” While it did inspire a trend of loading big movies with multiple major stars, it did not inspire copycat Westerns. It is, at times, a screwball comedy, paying silly homage to Charlie Chaplin. Its songs are among the most memorable of their era, performed off-camera by the great Kishore Kumar and Lata Mangeshkar, among others.

Not that I would know then, Bollywood itself was evolving. The previous decades featured the proliferation of art films by such greats as Satyajit Ray. Now, in the 1970s, Indian cinema produced numerous formulaic popcorn pictures, featuring melodramatic plotlines of forbidden love, formulaic fights between heroes and villains, lip-synched songs, and semi-random dance performances.

Among the central figures of this era were Rekha, Zeenat Aman, Dharmendra, generations of Kapoors (Raj, Shammi, Shashi, Rishi), Rajesh Khanna, Vinod Khanna, Hima Malini, and others. New star Amitabh Bachchan, however, eclipsed all of them, becoming the hero for every young South Asian boy across the world. By today’s standards of sculpted hair, manicured faces, and chiseled bodies, these stars may not be as memorable—I’m South Asian, we’re all gorgeous, sort of—yet they radiated such charisma that even the painted marquee posters were exciting to look at.

I wish I could, however, tap you into the way that film captured all of us. So many young men of my generation learned to love movies from their first experiences watching Luke Skywalker in “Star Wars.” For every moment my cousins, friends, and I swung wiffle bats in lightsaber duels, I am sure we quoted lines from “Sholay,” singing “Mehbooba Mehbooba” and “Yeh Dosti.” Yes, these two boys were punks, yes, they were incorrigible rogues, but they were also innocent, playful 13-year-olds trapped in the bodies of 20-somethings, forced to grow up in a harsh world. Every step of Jai’s swooning over Radha—straightening his posture, playing the harmonica in the distance, and speaking with manners—is a shy, pimply teenager’s hope to win his beloved’s approval, over her disapproval for everything he otherwise enjoyed fiddling with. In contrast, for Veeru, Basanti was the colorful, spunky force to be reckoned with whose shrugs would push him to swim in bottles of booze.

The friendship between the two young men, Jai and Veeru, carries the film to the end. These two lads enjoyed their pranks more for their partnership than the stunts. Today, we’d call each other our “ride or die.” Each time they have to decide on something, Jai flips a coin, and they race according to where the coin falls. In the movie’s climax, perhaps the only time they have to separate, Jai flips to decide who will risk his life crossing a bridge toward sticks of dynamite.

For so many of us young South Asian boys in the Subcontinent and (like myself) in the diaspora, Amitabh became our model of young manhood. Every few months, a local Chicago theater would pack the house with Amitabh’s latest. Soon, the arrival of VCRs allowed us to consume everything, and of course, we consumed “Sholay” more than all the rest. When an Indian kid enrolled in my Junior High, we became fast friends, spending much time talking about Amitabh.

On first glance, long before today’s toxic masculinity, he was in this film, and for most of his movies for the next two decades, the model “angry young man.” His manhood, however, was not a product of disobedience, domination, or insecurities hidden behind lavish lifestyles. Rather, his was a model of being unable to be anything but himself, the result of which was a long process of butting heads with everyone, while still trying to remain upright. And, yes, to my parents’ and siblings’ chagrin, I butt many, many heads.

This film was from an era in which it was still common to find sympathetic Muslims and Hindus in the stories, acting on camera, and writing and producing behind the scenes. In today’s India, it is still present, but it seems urgent against the nationalisms in India and beyond. I wonder if Amitabh is one of the few who can call on India and the world to come together in reconciliation. I would listen.

The newly-restored “Sholay” is currently screening at this year’s TIFF for its 50th anniversary.