James Cameron’s “Aliens” (1986) is rightfully regarded as one of the greatest follow-ups in film history. Even though it shares several elements with its predecessor, comparing them feels like a case of apples and oranges. Ridley Scott’s “Alien” (1979) is slow and involving; Cameron’s feature is one of the busiest, most chaotic movies in memory.

“Aliens” deals with the return of Ellen Ripley to LV-426, the planet where the Nostromo crew first came upon the title creature. Just a few days after waking up from a 57-year nap, Ripley learns that a colony set there 20 years before has recently lost contact with Earth and is eventually recruited to join a rescue mission. She embarks there with a group of Marines on an assignment to wipe out the creatures (why is it that characters in movies like this are never told about the nature of their mission before they have already traveled light years from Earth?). As with all of those “Jurassic Park” entries that “Aliens” inspired, the arrogant Marines will find themselves over their heads facing an almost unstoppable enemy.

Even though this is clearly a Great Movie, I wouldn’t go as far as to call it a perfect one. For a space feature set in the far future, it has too many elements that instantly give away the exact time period when it was made: Paul Reiser’s ’80s hair; its “widescreen” monitors that simply consist of old-fashioned, low resolution ones cropped with over lapping frames; and the unlikely prevalence of smoking (unless such habit does make a comeback and this prediction turns out to be true).

There are also several plot elements in “Aliens” that don’t make much sense. What was the point of taking a spaceship the size of a small city in order to transport no more than a couple dozen passengers? Why wouldn’t the Marines leave at least one person aboard the Sulaco while orbiting LV-426 (like their counterparts in the later “Alien: Covenant”) just in case something went wrong? And why do the surprisingly brilliant Aliens kamikaze themselves by the hundreds in order to grab a handful of humans, when the whole point of them going through this process is to be able to hatch their eggs and allow their species to flourish? (I think of the deleted scene where dozens and dozens of them are wiped out by unmanned machine guns).

Additionally, why is it that every sequel to the original “Alien” seems to overlook the fact that the creature’s acidic blood once almost blew a hole through the Nostromo, but when their characters are sprinkled with such, they simply get bandaged and move on? I was also under the impression that “Aliens” was a more original movie until I watched its predecessor’s DVD deleted scenes and ran into a sequence that depicts the creature’s modus operandi for reproductive purposes, an idea that was clearly written for the original. Still, these are all minor details that don’t take away too much from the movie.

Despite their many similitudes and a similar impact on the viewer, the first two “Alien” movies differ in one essential facet. Even though the emergence of Ripley as a most powerful presence is central in both features, motherhood is clearly the main theme behind the sequel. With this in mind, editing out the timeline that deals with Ripley’s own daughter (from the Special Edition) makes no sense whatsoever. The longer, and truly definitive version of the sequel is really about a mother who loses a child and comes upon an orphan in dire need of one, even if that means facing the ultimate menacing matriarch. This time around, Ripley is simply a woman forced to become a full-fledged warrior, with the strength to show up the terrifying Alien Queen with just a glance, in what is surely one of the greatest performances ever in such a commercial project.

Along with its off-the-charts intensity, Scott’s “Alien” became a classic thanks to several bravura sequences of immense shock value, like the chest-bursting creature’s debut, the milky revelation of the Science Officer’s true nature and the emergence of one the most unexpected film heroes in history. These sequences would seem impossible to top, but several moments in “Aliens” turned out to be just as good or even better. Just think of the jaw-dropping moment when Ripley accidentally enters a room that fully reveals how these creatures come to be. There’s also the film’s final sequence, structured similarly to that in the original (just when you thought the creatures are dead … ) but much more elaborate, giving a seemingly harmless contraption seen early in the movie the most unexpected use. This sequence is introduced by what is surely my favorite moment in the whole series (get away from her…!).

What truly makes “Aliens” even better than its predecessor is how it maintains a seemingly impossible fever pitch. You sit there in awe watching the film, realizing the great expectations that every sequence creates are invariably surpassed, and as much as you assure yourself that the following scene can’t possibly top the last, you are still astonished when it invariably does. This is the rare movie where I find myself pleading for a break in the action, which doesn’t arrive until the credits finally rolled. Cameron manages all of this, even when dealing with the disadvantage of having to work with elements previously familiar to the audience. Let’s face it, watching an Alien pop out from a human being the second time around isn’t remotely as shocking, as proven by every later entry in the series.

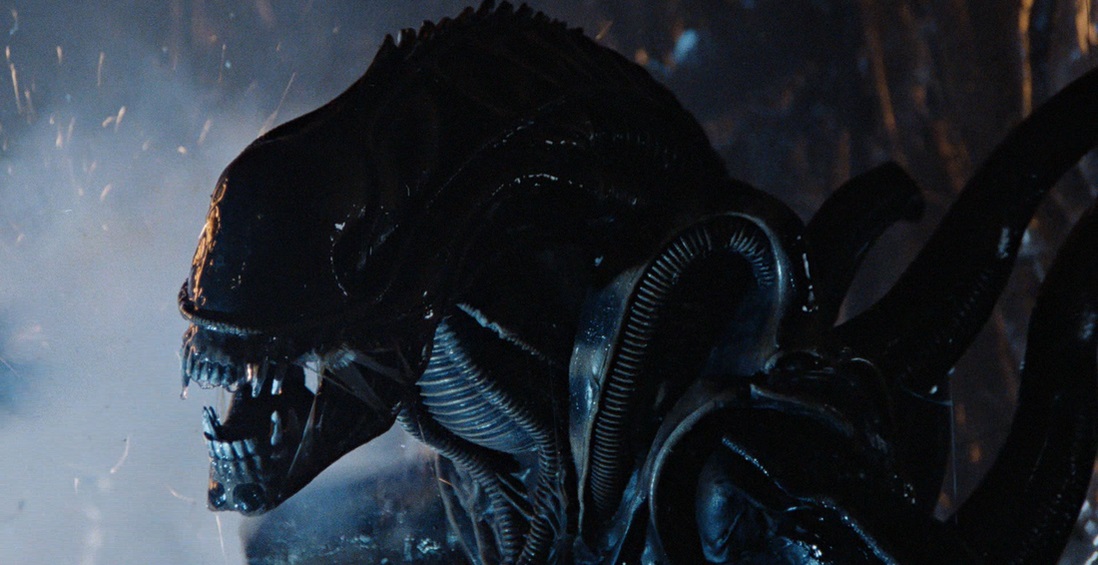

“Aliens” also doesn’t share the benefit of being able to gradually reveal what was once an unfamiliar creature (a la “Jaws”). Watching the movie recently I came to realize just many of its illusions are achieved through the magic of editing or through sheer ingenuity, as when several of the creatures attack the characters, all done with a single Alien suit, usually occupied by the same actor.

The special effects in “Aliens” may not live up to those in the more recent entries in the series, but, after all these years, most of them still look outstanding. “Aliens” represent action filmmaking at its finest, and no matter how many state-of-the-art techniques Cameron got to work with in his later movies, this is still his best.