Mike Nichols‘ 1971 drama “Carnal Knowledge” is part of a canon of American films of the late 1960s to mid-1970s that mirrored the freewheeling sexual culture and society from which they emerged. These films (“Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice“, “Shampoo” and others) examined varied notions of commitment, companionship and sex. “Carnal Knowledge”, written by playwright, author and cartoonist Jules Feiffer, shows men talking casually, bluntly and frankly about women, their bodies, of strategies to get sex and of sexual belt-notching, though not necessarily much about the specific act of sex.

Mike Nichols‘ 1971 drama “Carnal Knowledge” is part of a canon of American films of the late 1960s to mid-1970s that mirrored the freewheeling sexual culture and society from which they emerged. These films (“Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice“, “Shampoo” and others) examined varied notions of commitment, companionship and sex. “Carnal Knowledge”, written by playwright, author and cartoonist Jules Feiffer, shows men talking casually, bluntly and frankly about women, their bodies, of strategies to get sex and of sexual belt-notching, though not necessarily much about the specific act of sex.

Get the <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com/widget/our-foreign-correspondents-rebert”>Our Foreign Correspondents</a> widget and many other <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com/”>great free widgets</a> at <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com”>Widgetbox</a>! Not seeing a widget? (<a href=”http://docs.widgetbox.com/using-widgets/installing-widgets/why-cant-i-see-my-widget/”>More info</a>)

In “Carnal Knowledge” Jonathan (Jack Nicholson) is a commitment-phobic lawyer whose cynicism and seething anger at women informs all he does. His legal career develops in the 1960s and 70s. Before then, specifically in the 1950s, Jonathan and his fellow Amherst College best buddy Sandy (Art Garfunkel) look for women to end their spell as virgins. Sandy is shy. Jonathan isn’t. The conversation about sex, love and women over the film’s opening scarlet-red lettered titles against a black background perfectly illustrate the contrast between these men. For Jonathan and Sandy, sex is like breathing. Well, maybe breathing is secondary. Their sex lives are everything, more even, than what they want out of life itself. Jonathan and Sandy tell lies about things, but not necessarily about sex.

Out of the black background of the opening titles emerges Susan (Candice Bergen), bright, black sweater-clad, hopeful, wearing lipstick approximating the very scarlet color of the titles we’ve been absorbing. Susan is the first person we see. I often think the conversation we hear Sandy and Jonathan having over those opening titles are actually Susan’s own unspoken thoughts or assumptions about how men view many women as sex objects, or at least how some men do. Susan has the two men well-pegged, even before she enters the college mixer. She and the other women of “Carnal Knowledge” know men infinitely better than the men know themselves.

One early shot of depth and perspective frames Jonathan in a doorway observing Sandy and Susan but we view the trio objectively, with Sandy and Susan in the foreground. In the shot Mr. Nichols emphasizes distance and loneliness in Jonathan, a man bereft of attachment, filled with the narcissism accentuating his emptiness and sadness. The conversation between Sandy and Susan during this moment of distance and alienation of Jonathan is not off-handed: they talk about people acting differently with others according to situation and context. The words they exchange foreshadow much of “Carnal Knowledge”. Sandy and Jonathan often call each other bulls–t artists. In this early shot of flirtation and opportunity between Sandy and Susan, Jonathan seems to dominate the room at that dull college mixer, even though he stands far away at the door as an outsider the way Dustin Hoffman stood in a door but for very different reasons and perspectives in Mr. Nichols’ forerunning 1967 film “The Graduate“.

Unlike “The Graduate”, a sunny, light and playful film, “Carnal Knowledge” isn’t optimistic or farcical, and is shot by Giuseppe Rotunno in murky and often silhouetted and dark tones, even lurid and oily ones. “Carnal Knowledge” is claustrophobic and intense. The film sometimes behaves like a malcontented, antagonistic rat gnawing vigorously and cynically at an era of 1960s “free love”. Specifically, Jonathan is a grimy rat that cries free love but screams go f–k yourself after the deed is done. “Carnal Knowledge”, which depicts the shifting currents of male sexual “conquests” and what it means for one sex to “capture” or “get” the other, ushered in a new decade in 1971. Indeed, “Carnal Knowledge” feels more transitional, a caustic bridge from the brighter “Graduate” of the sex-crazed Swinging Sixties to a singular, colder 1970s film like “Shampoo”, which feels like a cautionary tale by comparison. “Carnal Knowledge” however, has no safety net and doesn’t profess caution or tread lightly. It barks, it’s shrill, it’s thought-provoking and it’s wildly funny, even uncomfortable.

Forty years ago “Carnal Knowledge” was deemed misogynist by some, but I don’t believe the film is. The women of “Carnal Knowledge” read men well, whether by their palms or their penises. There are plenty of women in the film and one or two girls, and Mr. Nichols shows us the difference between the two. The women are not victims of the film or the filmmaker. They are the put-upon that the film’s fragile, weak men have been propping up their low self-esteem against. If Jonathan lives in a world where he lives only for sex, then what is he? At one point he tells Sandy that “you’re happy, and I’m making money.”

Jonathan is undeniably a misogynist and a misanthrope, and objectifies women so relentlessly as to be vile. Played by Mr. Nicholson in his heyday of playing iconic counter-cultural characters in films like “Easy Rider,” “Five Easy Pieces” and “Chinatown” to name a few, as Jonathan he lacerates and burns in “Carnal Knowledge”, which sees the world largely through Jonathan’s lonely, arrogant and egotistical eyes. But “Carnal Knowledge” also indicts Jonathan and identifies him unmistakably as a sad, self-loathing creature shrouded in narcissism and denial.

Cinematically, a judgment of Jonathan is rendered and represented in a scene in New York City’s Central Park circa 1960s, in which Jonathan is framed against a backdrop of skyscrapers. Jonathan, like those skyscrapers, is mostly stone cold, unfeeling, inert; a man unlikely to change except to deepen his own anger for and resentment of women, as well as the hidden fear that in the act of sex itself there’s either nothing deeper or there are blips of feeling that may lead to something more substantial than sex. The shot of Jonathan against those skyscrapers is a powerful and revealing image. You can freeze the image in your mind or on the big screen or on DVD and it retains a power and a pathetic aspect that is sad, perhaps disturbing. In this same moment Jonathan despairs to Sandy about having had sex with “only” a dozen or so women annually. Times are tough. Against these concrete, phallic structures is a limp man initially in deep denial of his own impotence.

By contrast, Sandy, a deluded and sensitive man who possesses an air of smugness and self-satisfaction about his married life, responds to Jonathan’s sex frequency “problem” in the Central Park scene with one of the film’s funniest and most truthful lines. He questions why Jonathan doesn’t want to settle down. As Sandy asks the question, we see a couple walking and children running in the background behind him. Sandy wants a family (and has one.) The existence Sandy has is purposeful, even if the life he lives is somewhat mundane. But most of all, it’s a comfortable secure life, a life, however, which will be tested.

“Carnal Knowledge” uses women as symbols of reinforcement of Jonathan’s deep-seated hatred of them. He seems to have a talismanic angel in a woman who skates at the Wollman Rink in Central Park, a woman who can potentially show Jonathan the way forward in life — not just with women — but with himself. She appears in bursts of light that explode the jarring, heavy, often uncomfortable weight and banter of “Carnal Knowledge”. The bursts of light are white and bright. But Jonathan doesn’t appear to see the light. Later a young girl Jonathan speaks proudly of strikes a pose in a photo that strongly resembles the style and grace of the ice-skating figure that appears repeatedly in Mr. Nichols’ film, a provocative conversation piece that holds up superbly in this new century. Initially an unproduced play by the Bronx-born Jules Feiffer, a Pulitzer Prize winner, “Carnal Knowledge” made it instead to the big screen.

The film uncovers male body language, not at in response to the sight of women, but at the questions women pose to men, specifically Jonathan. When one woman poses a question to Jonathan about “shacking up” he freezes. Jonathan then sits down, and speaks, behaving as if he’s given a poorly-worded answer on a job interview. Ann-Margret, who played the stereotypical “bimbo” in the early part of her acting career, plays the antithesis of that stereotype as Bobbie, in “Carnal Knowledge” or at least Ann-Margret supplements the “bimbo” stereotype with some truths that deeply penetrate Bobbie’s air-headed veneer. There’s something subterranean occurring within Bobbie, and amidst the seriousness of her trials and tribulations Bobbie perhaps implicitly comments on Ann-Margret’s prior “bimbo”-type roles when she says of abuse, “you don’t know what I’m used to”, in response to Jonathan, who asks why Bobbie exposes herself to such abuse after an unsettling and volcanic tirade that feels like the film’s biggest, most devastating sledgehammer. Ann-Margret was Oscar-nominated for her supporting work in the film.

“Carnal Knowledge” was famously the subject of the U.S. Supreme Court in 1974, in Jenkins v. Georgia. The case involved a movie theater manager in Georgia who was arrested and convicted in 1972 of exhibiting “Carnal Knowledge” in his theater, a film deemed obscene by Georgia statutory law and the state’s Supreme Court. “Carnal Knowledge” was seized from the manager’s movie theater. The Jenkins decision, announced by the nation’s Supreme Court six days short of three years after the film’s June 30, 1971 premiere in New York City, found that “Carnal Knowledge” was not a film that was “patently offensive” or obscene and accordingly didn’t satisfy the U.S. Supreme Court’s standard for obscenity. The Court opined in a 9-0 ruling overturning the Georgia Supreme Court (and Mr. Jenkins’ conviction), that no gratuitous sex appeared in “Carnal Knowledge”, nor were any displays of male or female genitalia present, nor was the film displaying any “hard core sexual conduct”, nor was Mr. Jenkins, the Georgia movie theater owner, showing “Carnal Knowledge” for the purposes of sex exhibition.

Indeed, Mr. Nichols’ film, which often looks and feels like a documentary, isn’t a sexy movie; rather it’s a real, honest expression of some men’s pent up feelings and tensions that belie their insecurities about themselves and women. Mr. Feiffer’s incisive screenplay of tainted, nuanced characters – the women are more fully realized in subtle ways than the men – forms the backbone of a biting, well-voiced story about the intellectualizing of guttural articulations of male attitudes towards women and sex.

“Carnal Knowledge” is however, a cerebral and sensual experience, also sensual in its music, which moves from old-fashioned, traditional to organ to jazz to exotic and Far Eastern Indian music. Much of the film however, is left to the imagination. Sexual episodes are never fully shown. They are shrouded in Mr. Rotunno’s cinematic darkness. Participants are obscured. We hear a lot. We don’t see a lot. Some of the best moments in “Carnal Knowledge” are those in the afterglow of sex or the isolation of sex’s post-climax. No cigarettes are lit as extra dessert by the participants. Sex isn’t ceremony for men and women in the film; it’s just done. Shots of women near-catatonic, contemplating statements likely to freeze or cause a man to erupt, are priceless. These silent, internal monologues of women that we see but don’t hear are more effective than the male monologues that are actually dialogues with other men.

“Carnal Knowledge” shows men expressing their feelings, even if those feelings are coarse and extremely harsh. If men are said to be supposedly out of touch with themselves and their feelings, “Carnal Knowledge” shows that they aren’t at all. Even so, both Jonathan and Sandy are tone deaf to the emotional needs of women, and their own vacuity leads to perpetual upheaval in their lives. Women forever give these men doorways in life to express their true selves. Doorways are constantly part of Mr. Nichols’ cinematic apparatus in “Carnal Knowledge”, portals through which men could choose to access greater truths about how they see themselves and how they see women. The doorways and door frames are glimpsed. Sometimes men walk through them metaphorically in a search for that truth. Other times they do not. Most times Jonathan, especially, is threatened by women. He fears them as much as he hates them, referring to them as “ballbusters”.

“Carnal Knowledge” personifies the kinds of cerebral power plays men and women put on each other. Some men chase the elusive and the impossible and double cross their friends in the process. Some women pity such men and subtly play them against each other. Women in the film don’t compete with each other as much as they compete with Jonathan for his attention. Women are a potent voice of “Carnal Knowledge”.

Cynthia O'Neal plays Cindy, an attractive, assertive and slightly older upper-class woman whose sophistication and intelligence runs circles around Jonathan in one scene of dialogue, showing where the real power in Mr. Nichols’ film lies. Cindy is the Mrs. Robinson of a jaded new era: she’s a quieter, less obvious seductress of a man who is still a boy in many ways, and when it comes to men she’s seen that movie too. Cindy simply wants a man to get down to business and stop acting. Cindy may be the film’s female equivalent of Jonathan, but infinitely smarter, happier and more subtle. Completely comfortable in her own skin, Cindy is every bit Jonathan’s equal and more, not in espousing any sexist, chauvinistic sentiments but in confidence and attitude. In Cindy’s dialogue with Jonathan, the brief suggestion of her competence and sexual power not only over Jonathan but as an expression of her sexual awareness, perception and strength are among the sexiest though less fully-explored aspects of “Carnal Knowledge”.

Mr. Nichols frames Ms. O’Neal’s Cindy in a shot standing in an adjacent room through a doorway during a scene between Jonathan and Sandy that is cinematically symmetrical to the early shot of Jonathan in the distance in a doorway observing the foreground conversation between Sandy and Susan. Unlike Jonathan, Cindy is relaxed, dancing, and carefree in the distance. Cindy may be the only character in “Carnal Knowledge” who is relaxed and relatively trouble-free.

Throughout Mr. Nichols film, a comedy-drama, there’s lots of tension between the sexes but also between the men, who dissect women as if they are pieces of meat on a plate waiting to be gobbled up. As the king of players at a sexual dinner table Jonathan doesn’t have the time to exhale. He wolfs down his food. And he’s always thinking about the next meal.

“Carnal Knowledge”, which on the surface is about a man’s knowledge of a woman’s body, mind and her attitudes toward men, contains subtext about a woman’s acumen of men’s bodies, minds and their attitudes toward women, as superbly and erotically summarized by Louise (Rita Moreno) in one scene. Louise is a definite snake charmer, a feminine mirror held up to one male character, and, as shot by Mr. Rotunno in one specific sequence, is arguably the most cinematic phallic symbol in the film. Louise may be seen as a controversial figure because she gives a strong sense of validation to Jonathan and his sexist, chauvinist behavior, rationalizing it in benign terms. She also validates Jonathan’s exposing truths about women. Louise is the film’s psychosexual epilogue, an escape hatch for Jonathan, who never truly has to feel. But is Louise accommodating Jonathan, patronizing him, or enabling and re-affirming his own insecurities? “Carnal Knowledge” functions as a trapping of male fantasies that wreck women, and Louise’s assessments may ultimately be a back-handed put-down of Jonathan.

“Carnal Knowledge” works as an open-ended play on the contrasting languages spoken by men and women to themselves and each other, whether that language is graphic, muscular and incorrect, or unspoken, suggestive and saucy. The home-made movie Jonathan plays during the film, complete with his droning commentary, exhibits his perennial boy-who-won’t grow up id. Years after graduating Jonathan’s still mentally trapped in college, an everlasting virgin despite all the sex he’s had. The more sex Jonathan has, the less he’s penetrated his own meaning in life, even as friends and acquaintances have supposedly matured. Yet Jonathan, as mentioned earlier, defines himself by his own sex life, so he believes that he’s graduated as a straight A student, with magna cum laude honors to boot.

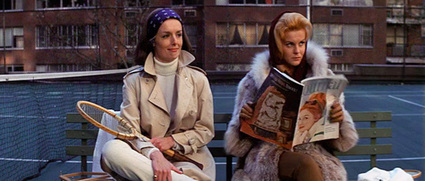

Men are constantly judged in the film. In the 1950s portion of “Carnal Knowledge” Mr. Nichols fixes his camera on Susan (Ms. Bergen) during a scene where she’s the focus of a night out at a bar with Jonathan and Sandy. Susan has the upper hand, in a moment that wonderfully supports the previous points she makes to Sandy early on in the film about acting differently with different people. In this subsequent bar scene Susan is the net that stands between the two male players on an imaginary social tennis court, male players who lob verbal hits to each other. Susan laughs at their jokes but she could easily be laughing at, not with, both Sandy and Jonathan, neither of whom we ever see in the shot. Later, Cindy and Bobbie are seated on a bench at a tennis court watching Jonathan and Sandy play tennis. Again, we never see either Jonathan or Sandy play. The scene is exclusively about women and their silent judgment of men. Ann-Margret’s expressions in the scene speak volumes. In another scene Jonathan is seen looking blankly ahead, and we are locked on him as Sandy and a woman are conversing. Not only does Jonathan look clueless, but he looks irritated and sad. Emotion and feelings that aren’t sexual are unpleasant background noises to Jonathan.

“Carnal Knowledge” is not only about judgment and sexual performers, companionship seekers and phony, deluded idealists but also about male self-esteem and how it is falsely bolstered or lowered by a male rival’s own sense of success with women, and in the process how men’s sex-related insecurities about themselves rise or fall according to their male rival’s physical success with the opposite sex. Does Jonathan “measure up” in a world of other men beyond Sandy? (Most telling is that Jonathan and Sandy are the film’s only male characters. When Jonathan talks about a man on the skating rink in Central Park, the camera doesn’t show him. Since the movie is more or less seen through his eyes, is Jonathan also fearful of men?) Is Jonathan a skyscraper of male sexism who will ultimately get knocked down or get his comeuppance? Note: Don’t ever tell Jonathan that “the sky’s the limit.”

In Jonathan and Sandy’s eyes, women have their “place”, and are responsible for ordering, situating and reinforcing the world that men live, work and operate in. Sandy, hardly a saintly figure in Mr. Nichols’ sex opera, remarks about the “order” his wife gives him when he comes home from work; that his kids are present, and his food is ready. This is the familial world of the homemaker, the very world that Jonathan partially if not totally rejects with one of the women he’s involved with.

“In the Company of Men” (1997), written and directed by Neil Labute, is an homage of sorts to “Carnal Knowledge”, although in Mr. LaBute’s drama the men lack introspection or appreciable depth. The character types though, are in place: the type-A domineering, charismatic s.o.b. played by Aaron Eckhart, and the weak, cowardly schmuck of a male sidekick (Matt Malloy) who thinks he’s on the right side of it all. Both are shallow figures emotionally, however. Unlike Mr. LaBute’s film though, “Carnal Knowledge” isn’t about gamesmanship between men in corporate environs, it’s about the sexes’ gamesmanship of the opposite sex. Mr. Nicholson’s Jonathan is more vicious and visceral in his hatred of women than Mr. Eckhart’s conniving Chad is, but both leave a mark, and one of them is more injurious to people than the other.

Years ago when I first saw “Carnal Knowledge” I thought it was rude but not necessarily crude. I heard younger men and boys talk like Jonathan did all the time. I’d like to think that I had a clean mouth on a general basis each and every day in my life although for some time it embarrassed me to even think in the vulgar manner that Jonathan volcanically and dispassionately speaks in. I knew that the men of Mr. Nichols’ film were weaker and more pathetic than they showed but I didn’t appreciate how good the performances were. Decades later, the film’s performances are more powerful than they were when the film debuted in 1971. “Carnal Knowledge” contains language that for some viewers will be shocking even by today’s standards, not necessarily because of the specific words, but because of the literal, adult and thoughtful approach Mike Nichols and Jules Feiffer take with this greasy, grimy material. The whole creative and collaborative team hits a grand slam home run, and that ball hasn’t come down from the sky since.

Omar Moore can be found on Twitter @popcornreel. He blogs at popcornreel.com.