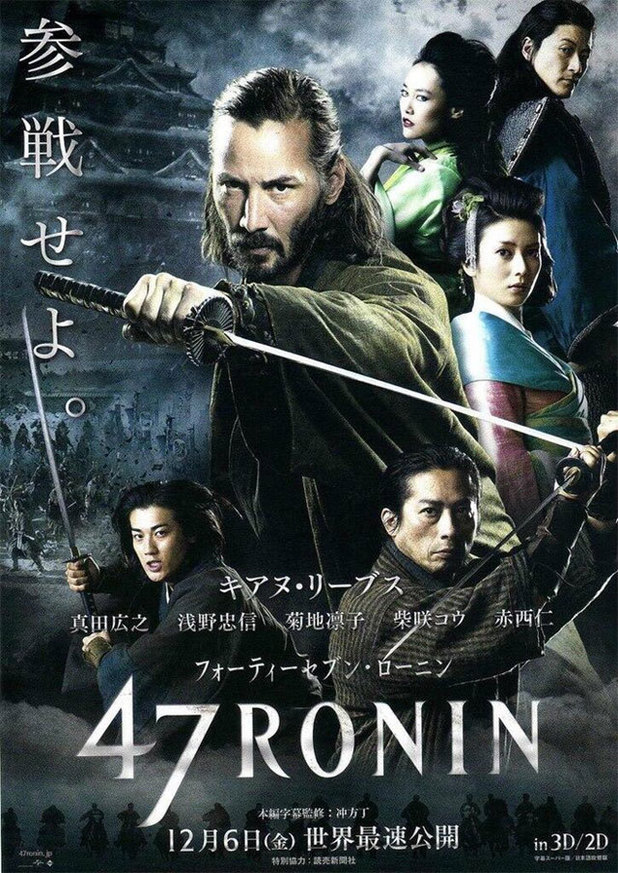

The rumbling could be felt before San Diego Comic-Con. Dark Horse was hurrying to get out their version of the Japanese loyalty saga of the 47 rōnin—they wanted theirs out before the release of the Universal movie. A look at the first trailer for “47 Ronin” gave fans an idea that the animated trailer only solidified. What Universal was trying to sell was new wave Orientalism.

By Orientalism I mean the belief that one theory of culture could be used to describe all the peoples from North Africa to the Pacific Islands. I’ve felt uneasy sweeping winds of Orientalism even as a graduate student when I argued that to describe someone as Asian didn’t paint any more detailed a picture than to say someone was European. We expect to know there are differences between Italians and Germans, even if they were allies during the last official world war, yet not with the Japanese and the Chinese, who were not.

Sure, a person of East Asian ethnicity can sometimes pass for Japanese or Chinese or Korean when they are not. You’ll get no argument from me there and that has been one of my favorite games when in Japan or parts of China and even Korea. Yet in the case of a historical drama, there are many differences and Universal’s team for “47 Ronin” ignored cultural differences of clothing and dress between Japan and China.

Samurai films are very popular in the United States and one festival in Los Angeles was founded specifically to counterbalance the lopsided image of Japan that resulted from the focused importation of Japanese samurai films and videos over other popular genres. With that in mind, people in America (as well, of course, as Japan) know what a samurai should look like.

The samurai had a specific hairstyle, chonmage. Nagisa Oshima’s 1999 “Gohatto”(御法度) or “Taboo” pointedly pushes this issue as the protagonist, Kanō Sōzaburō (Ryuhei Matsuda), refuses to cut his hair to conform, resulting in tension within an elite samurai group. In the 2002 Oscar-nominated “Twilight Samurai” or “Tasogare Seibei” (たそがれ清兵衛), before Iguchi Seibei (Hiroyuki Sanada) goes out to battle, because he has no assistant, he asks his childhood sweetheart to help him perform the traditional rituals, including shaving and styling his hair.

Both movies are set at the end of the Tokugawa period (the 1800s). “The Last Samurai,” which is mentioned in a Variety article by Ramin Setoodeh and Scott Foundas, is also set in that time period. For the most part, the traditional samurai hairstyles were used in that Tom Cruise movie.

The proper hairstyle also comes up in Takashi Miike’s 2011 “Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai” or “Ichimei” ( 一命 ) a remake of the Masaki Kobayashi 1962 “Harakiri” (切腹). Both Miike and Kobayashi’s movies are set between 1619-1630. In both movies, samurai fake being sick because their top knot has been cut off.

Historically, “47 Ronin” is based on the Akō Incident of 1703. People know what samurai are supposed to look like before, during and after that time, and the filmmakers of Keanu Reeves‘ version ignore that. We see the samurai with long hair and, before their ritual suicide, a funny bun on the top. Compare that to the 1991 version of “Chūshingura.”

For the women in “47 Ronin,” some of the hairstyles are more Dr. Seuss or Marie Antoinette meets kabuki than court style. Wavy hair was considered bad hair for Japanese women, something that has been pointed out to me in Los Angeles in modern times—the prejudice lingers. Further, what aristocratic woman would be without her ladies in waiting in Japan or any other royal house—not that the women are really aristocrats.

During the Tokugawa period, Japan was ruled by the Shogunate through the aristocracy. The emperor was a puppet and he held his puppet court in Kyōto. The shogun was in Edo (now Tokyo). In the original version of the tale, an imperial envoy was sent annually to the shogun in Tokyo and the shogun’s master of protocol, Lord Kira, supposed to instruct the Lord Asano on proper manners for the occasion. Yet in this 2013 version it is the shogun visiting Lord Asano and the shogun is addressed as your “highness” instead of using a military term. Is that a mistake in translation or just ignorance on the part of the screenwriters?

During the Tokugawa period, there was a rigid four-class system: samurai, farmers, artisans and merchants. The aristocracy was above system. Also outside the class system were the Ainu, the burakumin, actors, criminals, prostitutes and courtesans.

This 2013 movie repeatedly implies that Keanu Reeves character can’t be a samurai because he’s a half-breed. Yet during that time period only samurai were allowed to have swords and knives. A peasant could be killed on the spot for possessing a sword and we are repeatedly told that his character, Kai, is the son of a British sailor and a peasant. I’m not saying that there wasn’t and isn’t prejudice against mixed race persons in Japan, but that class was an important factor during the Tokugawa period. Kai was of the peasant class through his mother.

Although I am not a native speaker of Japanese, I have been told that originally there was no word for privacy in Japan. In a country with walls that might literally be made of little more than paper, it is hard to get real privacy, so to a large extent, privacy is a mental state.

You can’t feel the claustrophobia of the mountainous island nation of Japan in this movie. Some of the scenes, perhaps filmed in Budapest, make the castle look vast and Japan filled with long, flat plains. Further, geography is all mixed up. The warriors travel easily from the Tokyo area to Deshima, the Dutch colony in the bay of Nagasaki, where Keanu Reeve’s character is fighting monsters. Yet in reality that’s a journey that would require 205 hours on foot according to Google maps (or 8 hours by public transit).

You get a sense of geographic confusion when you see the castle of the evil Lord Kira is shown as being in a dark and cold place and yet other scenes are in a bright place with cherry blossoms blooming. Cherry blossoms generally bloom in April and not for long. The winters in Tokyo are generally bright and dry. Instead of studying geography, the writers seemed to have fallen back on emotional scenic design. Dark and cold means evil. That didn’t work for me in the 2013 “The Wolverine” when the action could have taken place in the distant north and it doesn’t work for me here during the Tokugawa period where the fastest mode of transport is a horse.

Turning the story of the 47 Ronin into a white-man-saves-the-day spectacle is cultural imperialism and in this day and age, that might have been a bad judgment call. The need to insert Keanu Reeves as a half-breed reminds me of Raymond Burr in the 1956 “Godzilla, King of the Monsters!” Is a white man—or in this case a half-white man as in the 1972-1975 “Kung Fu” TV series—really necessary after the success of Ang Lee’s 2000 wuxia film “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” or his 2012 “Life of Pi“?

While the dragon in Ang Lee’s movie wasn’t real or even CGI, the dragon in “47 Ronin” is not Asian. Dragons are considered lucky in China and Japan, but the evil enchantress becomes a dragon in the “47 Ronin.” Dragons are associated with wind and water in Asia, but this CGI dragon is one that breathes fire. The script does incorporate Japanese legendary characters: the tengu who are mountain warriors and the fox who can transform itself into a beautiful woman, but brings in one unnamed beast instead of incorporating the kirin or the kappa. And why bring in that nameless beast for one appearance?

The kind of imperialism of this version of “47 Ronin” isn’t as bad as the 1939 “Gunga Din” which was banned in India at the time but somewhat insensitively was used later as the inspiration for many scenes in 1984 “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.” The movie “47 Ronin” has a half-white character teaching the Japanese how to handle Japanese beasts and the true nature of bushidō.It fuses Japanese and Chinese culture with Western in a way that might be more digestible if this were food and not a movie.

The Variety article by Setoodeh and Foundas says that the film when it opened in Japan “needed support from the region, where the cast was well recognized. But it never gained traction there…Market research showed the key demographic of young men didn’t buy enough tickets.”

Why would young Japanese men buy tickets to this movie? The advertising for the movie clearly shows that the production team doesn’t understand what makes a woman sexy in a kimono. (It’s not the cleavage, it’s the back of a woman’s bare neck and the glimpse of her white foot.) The trailers depict the samurai without the hairstyle of their class. Should a tale about Japan seem more Japanese?

While the Variety article suggests the first-time feature director Carl Rinsch didn’t find a “balance between classic Eastern tale and the more Western touches” and that Rinsch wanted a more arthouse samurai film and also talks about the many writers (Chris Morgan and Hossein Amini) and many editors, what about finding the Japanese part of a story set in Japan?

Traditionally the story of the 47 rōnin, known as Genroku Chūshingura (the Genroku era loyal retainers), is about the conflict between human feeling (aijo) and duty (giri). Having Japanese actors as Japanese is a start and preferable to yellow face, but that isn’t enough to make a good movie about Japan. Adding some Japanese items like swords and Japanese style armor, Japanese mythical creatures or a cherry tree doesn’t make something Japanese. In my opinion, the “47 Rōnin” failed as a movie because it didn’t respect the culture or traditions of Japan or the samurai, or show respect for the fans of either.