When I entered the music program in my first year of university, it seemed impossible to avoid conversations about “Amadeus.” It helped that the Miloš Forman movie was relatively recent and happened to be good. But something else set it apart from films about classical composers. It managed to take you inside the heads of Mozart and Salieri—the former a musical genius, and the latter, as Roger Ebert put it, with “the talent of a third-rate composer but the ear of a first-rate music lover.”

In a scene midway through the film, Mozart’s wife Constanze meets court composer Salieri on the quiet, hoping to convince him to give her husband more work. She shows Salieri some of Mozart’s original compositions. As he flips through the scores, you hear the piece that’s written on the page. But you’re not just hearing the music, you’re listening to how those notes translate to Salieri, and how their perfect arrangement taunts his inadequacy.

The movie often plays with that: who’s hearing the music, and how are they hearing it? It happens when the Emperor plays a march Salieri wrote for their first meeting with Mozart, who, in turn, plays it back moments later with considerable improvements, in part to show up Salieri and his terribly simplistic piece. There’s also the ending, when both men finally come together to write Mozart’s Requiem. The genius is in a hurry to put it all on the page; the non-genius wants a minute to take it in.

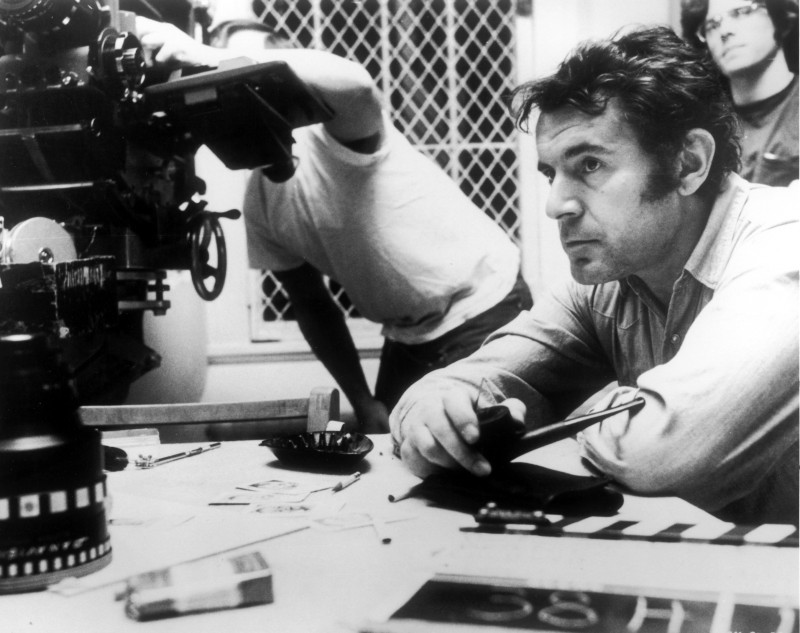

You might attribute these storytelling aspects to Peter Shaffer, whose play was adapted into the film. But Forman created another language for Shaffer’s ideas. He messed with how a stately period drama is supposed to behave with Tom Hulce’s falsetto laughter and those hard rock wigs, which aren’t a nod to wacky ’80s trends so much as a manifestation of Mozart’s nonconformity. It doesn’t matter that the story is anchored in fiction because the movie isn’t interested in who those people really were. It’s about prodigy, mediocrity, and what it’s like to occupy both of those internal spaces.

You get a better glimpse of that in “Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond,” a behind-the-scenes documentary about Jim Carrey’s literal transformation into Andy Kaufman during the filming of “Man on the Moon.” Here, Forman is remarkably indulgent of his leading man’s inconvenient method acting, even calling him “Andy.” Carrey’s process is at times unproductive, but Forman finds a way to work with it.

In an earlier interview about “Man on the Moon,” when Forman describes Kaufman’s comedy, he’s both baffled and fascinated by it. But there’s delight to spare for Carrey’s madness as well. Carrey offers an explanation: “[Forman] is a big artists’ rights person. He believes in the artist. He believes that these expressions and these choices happen for a reason.”

It suggests that Forman supported anything that might help performers tap into an essential humanity, which created beautifully complex characters that played against expectations.

Consider Nurse Ratched’s cool head in “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” It would be difficult to size her up based only on the words she says, which are few and achingly calculated. What you know about her is the effect she has on the men in her ward. Though it’s not just the fear she inspires in her charges. You also get the sense that exercising that much control over them requires a combination of indifference and disdain. She doesn’t really care what happens to them, and they probably pick up on that.

During ensemble scenes, Forman gives the actors carte blanche to amplify their characters, and the conflicts often become chaotic, lending necessity to Nurse Ratched’s composure. These are different people who want different things at the same time, which feels authentic. They’re not all fleshed out on the page, but each exists fully in those scenes.

<span id=”selection-marker-1″ class=”redactor-selection-marker”></span>

If a Forman movie wasn’t a careful character study, it likely dealt in extremes. “Hair” could have been a trippy film about singing hippies, but it instead reminded us that they were part of an upheaval, and largely up against very powerful, decidedly non-hippy forces. And while “The People vs. Larry Flynt” has a lot of the beats you might expect from a biopic—briskly jumping from one milestone moment to the next—its main subject is a man who went where even Hugh Hefner dared not go.

Some directors are all about the visual symbolism, but Forman was more of a people-watcher. He was curious about the inner lives of his characters and the context that made them significant. Each person in a scene mattered, even if the scene wasn’t about them. It’s why Constanze swipes one of Salieri’s pastries while his attention is on Mozart’s scores. She loves her husband, but she also has a sweet tooth.