“I don’t want to live

in a world where there are no lions anymore.”—Werner Herzog

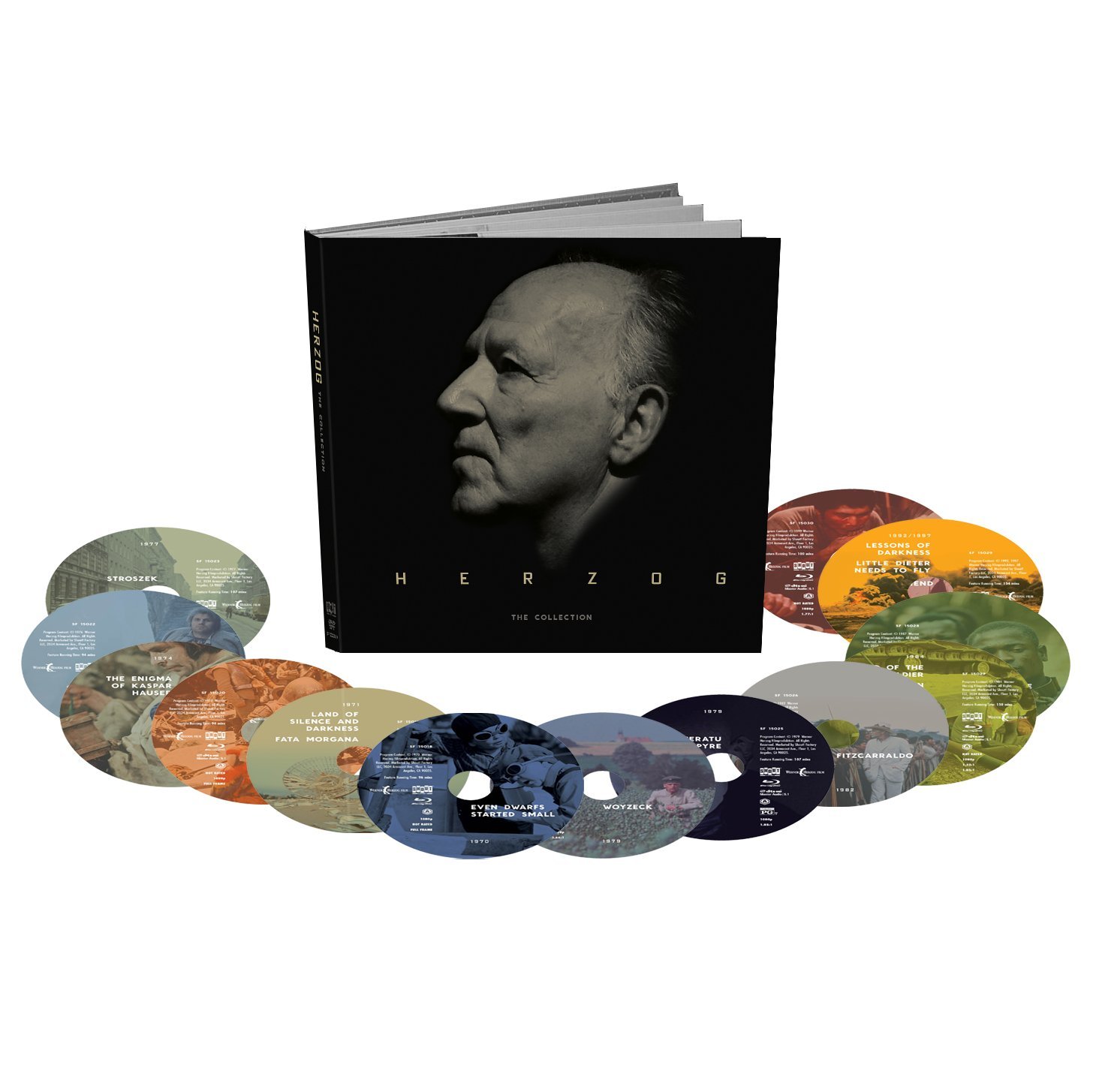

The Blu-ray event of the year for most serious film lovers

is Shout Factory’s “Herzog: The Collection,” in stores this week. With gorgeous

packaging, including quotes from many of Roger Ebert’s reviews of Herzog’s work

peppered throughout, the set marks the HD debut of fifteen of Herzog’s films

from the ‘70s to the ‘90s (with a 16th film having only been released

on Blu-ray for the first time this year… so they’re really all new to HD). The

Collection allows true cineastes the chance to not just appreciate these films

individually but also see how Herzog’s aesthetic developed over the first three

decades of his life in cinema. Herzog’s filmography has always had a remarkable

flow as his films not only seem thematically related to one another but often

comment on each other or echo previous characters and concerns. Given Roger’s

close relationship with Herzog and the overall cinematic value of this set, we

thought we’d take the opportunity to examine the entire Collection, film by

film, disc by disc.

Watching sixteen Werner Herzog films in a short period of

time, one can easily see their connections and the filmmaking patterns of their

creator. He rarely includes images of overt sexuality or even violence,

although the constant threat of the latter in our society permeates a number of

his narratives. He even more rarely underlines an emotional moment or uses manipulative

filmmaking techniques. He says on the commentary for “Nosferatu: The Vampyre,” “I don’t want to see an actor cry, I want to

see the audience cry,” to explain why he would take a scene most directors

would shoot in close-up—that of Jonathan Harker saying goodbye to Lucy—and

shoot it from behind and from a distance. From the kind of basic filmmaking

habits one notices while watching a career progress on Blu-ray—Herzog often

opens his films with a mood-establishing shot about the power of nature (from

the storms of “Where the Green Ants Dream” to the foggy hills of “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” to

the unforgettable prologue of “Heart of Glass”)—to the more complex themes that

keep popping up in Herzog’s work to his tumultuous relationship with Klaus

Kinski, this is the kind of Blu-ray experience that truly allows for a greater

appreciation of one of our greatest filmmakers.

“Even Dwarfs Started

Small” (1970)

The collection starts with Herzog’s third film, the story of

an institution overrun by the inmates, cast entirely with dwarfs. Herzog’s

organic approach to filmmaking is immediately apparent. The world and the

“characters”—who were barely given a narrative to work with and were often

directed improvisationally by Herzog—feel real. We hear a light switch and the

lighting in the scene comes from that switch. A dwarf is directed to hold a

sign higher and look to the side. He does. It is clearly not Herzog himself

giving those directions and yet it may as well be, setting the filmic precedent

for much of what he would create in the future. In the first crowd scene, the

characters all look directly at the camera.

Throughout “Dwarfs,” one can feel Herzog behind the camera,

urging on the fight scenes and the increasingly anarchic behavior. It has a

sloppy, unformed feel that might allow it to verge on exploitation for modern

audiences, but that unease is part of its creator’s intent. He wants you to

feel uncomfortable. “Dwarfs” now feels more intriguing in the context of

Herzog’s overall filmography as one can easily see the theme of how revolution

often leads to disorder is one that he would revisit with greater artistic

success later in his career. It’s a terrific start to the Collection in that

it’s a warm-up for the greatness to come.

Special Features: Audio Commentary with Writer/Producer/Director

Werner Herzog and Actor Crispin Glover, Moderated by Norman Hill

“Fata Morgana” (1971)

The second film in the collection started life as an

entirely different project, a fact, in and of itself, that speaks to Herzog’s

abilities to bend with the curve of the cinematic river. He took a film that

began life as a sci-fi project and transferred its alien landscapes into what

is essentially a visual meditation on the unique world in which we live. The

film opens with multiple plane landings—the jet streams, the sound a plane

makes when it lands, even a brief taxiing before cutting to the next one, which

always starts about mid-frame. It’s a visual and aural table-setter for an

experience that is primarily image and sound, both of which have been expertly

transferred to Blu-ray.

Many of the images in “Fata Morgana” have a puzzle-like

quality—”What am I looking at? Why is Herzog showing me this and from this

angle?” Despite its curious origins, “Morgana” is clearly an ancestor of

Herzog’s recent work in what could facilely be called his “Mother Nature”

documentaries—such as “Cave of Forgotten Dreams” and “Encounters of the End of

the World”—films in which the wonders of the real world perform greater visual

miracles than any CGI house could possibly hope to replicate.

Special Features: Audio Commentary with Writer/Producer

Werner Herzog and Actor Crispin Glover, Moderated by Norman Hill

“Land of Silence and

Darkness” (1971)

Again, through this release, this work can be fascinatingly viewed as a precursor to so many of the thematic motifs that Herzog would later

return to—primarily how we use our senses to interact with the world around us.

In one of Herzog’s more traditional documentaries, he introduces us to people

who are deaf and blind. It opens with a woman describing images that she can

only see in her mind and Herzog shows them to us—a horizon, ski jumpers, and so

on. The concept of the director as a visualizer of the mind’s eye is a classic

representation of a filmmaker but one that still resonates, perhaps even more

strongly given that this woman will never see these images herself.

It may be purely chronological, but “Land of Silence and

Darkness” really does make for a perfect companion for “Fata Morgana,” and

they’re included on the same Blu-ray disc to make the double feature easy.

Whereas “Morgana” opens with images and the deafening sound of a plane landing,

the women in “Land” can only describe what they remember seeing and hearing.

And, when Herzog takes them on a plane ride, we can really only imagine the

sensations they’re experiencing. Herzog is a man so deeply in tune with the

sights and sounds of our world that it makes sense that people trapped in

silence and darkness would fascinate him. They live in memory while Herzog the

filmmaker captures the now.

Herzog’s camera work here is restrained, always handheld,

and never cutting to “coverage” or zooming in on faces to provoke response. It

makes us feel like a visitor more than a film watcher. Throughout his career,

Herzog will try to take us to places and show us things we would never

otherwise experience. While “Land” may not detail a physical journey like so

many of his most beloved works, it is nonetheless a journey of its own kind.

Special Features: None

“Aguirre, the Wrath

of God” (1972)

Speaking of journeys, cinematic ones don’t get much more

remarkable than the film widely (and correctly) considered as Herzog’s

masterpiece. “Aguirre” has lost none of its power in the forty-plus years since

its release and the Blu-ray transfer here wisely doesn’t over-polish a film

that demands a bit of grit and grain to convey the reality of its setting.

“Aguirre” is still the perfect blend of realism and fiction.

It is the story of a journey through dangerous lands and treacherous terrain

that itself was a journey through dangerous lands and treacherous terrain. You

can feel the production dancing on the edge of sanity and how that influenced

the storytelling. There is such a fascinatingly tactile world created in

“Aguirre.” When the characters struggle to traverse muddy terrain, it is the

actors and the entire production that is struggling as well.

The well-documented, behind-the-scenes drama of modern filmmaking

often drains a film of its power. “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” has the opposite

story. The widely-reported stories of battles between star Klaus Kinski and

Herzog, who was only 28 when he made it, add an extra layer of tension to the

narrative rather than breaking the illusion. It’s because, for Herzog, there

isn’t the same degree of illusion as most filmmakers. He’s not as interested in

the illusion of filmmaking as he is in the realism of it. And so Kinski would

become his greatest collaborator, inspiring him the way that a seemingly impenetrable

challenge inspired Aguirre or Fitzcarraldo. More on that later. Just see

“Aguirre” again if you haven’t done so recently. You won’t regret it.

Special Features: Audio Commentary with Writer/Director

Werner Herzog, German Audio Commentary with Werner Herzog, Moderated by Laurens

Straub

“The Enigma of Kasper

Hauser” (1974)

I vastly prefer the original German title of Herzog’s Cannes

Grand Jury Prize winner, “Every Man For Himself and God Against Them All.” It

captures more of what this often-mesmerizing film conveys—the futility of

trying to control your fellow man. Reportedly based on a true story, the film

details the odd case of Kaspar Hauser, a man who lives the first 17 years of

his life in complete solitude and is then thrust upon a German village, where he

becomes something of a local celebrity. He’s first a circus freak and then an

oddity for socialites to admire. And, of course, it doesn’t end well.

“Kaspar Hauser” is the first widescreen Herzog film in the

collection and arguably the entire set’s most lyrical and contemplative, yet

even here Herzog is playing with the form, most notably in casting a non-actor

in the title role. Bruno S. was a street musician with no acting background and

a disturbing personal history of child abuse. He spent most of his life in a

mental institution, although Herzog never believed him to be mentally ill nor as handicapped as some thought. Whatever Herzog believed to be true or untrue

about Bruno S., the actor’s child-like demeanor certainly changes “Kaspar

Hauser.” There’s a moment late in the film in which Hauser goes to play piano

in front of a group of socialites and Bruno S. looks directly at the camera

when he introduces the piece, almost making us a part of the party. Did Herzog

direct him to do that? Did he do it on his own? (Bruno often glances at the

camera in both this and “Stroszek.”) Is it the actor or the character changing

the aesthetic of that scene? The line is blurred and it doesn’t matter.

Take the story that Kaspar Hauser tells at the end of the

film. It’s revealed in Herzog’s fantastic commentary that it’s an idea that the

director wanted to one day turn into a film of its own but that he could never

quite complete. Kaspar Hauser, the fictional character based on a real one, is

relaying the incomplete vision of the filmmaker.

Special Features: Audio Commentary by

Writer/Producer/Director Werner Herzog, Moderated by Norman Hill

“Heart of Glass”

(1976)

One of Herzog’s most divisive films feels somehow more

captivating and, well, hypnotic viewed on Blu-ray and in the heart of this

collection. One can more easily see how it fits into the landscape of Herzog’s

vision of the drastic impact of change on the natural world and organic order

of things. The story goes that Herzog actually hypnotized most of the cast of “Heart

of Glass,” the tale of an 18th-century Bavarian village that’s

shaken by the death of the one man in town who knows how to produce the legendary

ruby glass for which it is known. The dazed, apathetic line delivery from most

of the actors lends credence to this filmmaking legend, resulting in a film

that could be frustrating for those who prefer traditional narrative but that I

find defiantly unapologetic and uncompromising. Herzog never produced a frame

of film that felt like someone else’s vision and “Heart of Glass” comes so

distinctly from his creative vision that it’s hard to dismiss.

Again, we’re blurring the line between traditional

filmmaking and reality. Instead of telling the story of people who seem stuck

in a daze, a walking hypnosis, he reproduces that state of being in his cast,

giving them lines of dialogue and motions the way a nightclub performer might

make a suggestible tourist perform. Is this “acting” by its traditional

definition? Who cares what it is “traditionally” if it fits Herzog’s vision?

There are also moments of painterly beauty, enhanced by HD

here, that hint at the evolving visual style in the next phase of Herzog’s

career. The prologue, with its clouds rolling over the Bavarian landscape, is

well-known, but “Heart of Glass” is imbued with emotional compositions

throughout. It’s the first film in this set that conveys a deep sense of loss

and dread. Times are changing. We’re all going to be shaken out of our

hypnosis. I understand that “Heart of Glass” is one of Herzog’s least

“accessible” films, but it’s designed that way, as if he’s challenging you to

let go of your filmic preconceptions.

Special Features: Audio Commentary with Writer/Producer Werner

Herzog, Moderated by Norman Hill

“Stroszek” (1977)

After realizing that he needed to reunite with Kinski for

his next film, “Woyzeck,” Herzog wrote this wonderful oddity for “Kaspar

Hauser” star Bruno S., reportedly in only four days’ time. Stroszek is a Berlin

street performer increasingly down on his luck. He moves to Wisconsin with a

German prostitute and, well, life doesn’t get much better. It’s easy to see

“Stroszek” as a commentary on the easy deconstruction of the American Dream,

but there’s such an easy-going, light tone to the piece that describing it in

such strong terms could be misleading. Herzog, inspired by time spent with

Errol Morris, presents American life in a series of vignettes that remind me of

the great American directors both fictional and documentarian. There’s a

definite commonality in the way Herzog captures Americana to the way Morris

would in his early films like “Vernon, Florida” and “Gates of Heaven.” And the

vignette approach to storytelling reminds one of Robert Altman’s brilliant

chronicles of big characters in small towns.

What’s so memorable about “Stroszek” is its free-flowing

lack of definition. At first, it feels like one of Herzog’s least serious or

existential films, especially coming after such a distinctly unique experience

as “Heart of Glass.” And yet, right from the beginning, there’s the odd

undercurrent provided by a non-actor like Bruno S. in the lead role. When he’s

being advised to stop drinking to turn his life around and Bruno is ranting and

raving, it’s unsurprising to hear on Herzog’s commentary that Bruno’s speech

wasn’t written for him. The moment feels real.

There are moments of broad silliness in “Stroszek,” and the

ending is truly masterful, but there are also beats of great, beautiful

stillness. There’s a beautiful moment when Eva puts her arms around Stroszek from behind

and he closes his eyes for a beat that feels like true peace. Is that Bruno S.

or the character finding that calm? Does it matter? And we find ourselves

rooting for this character and all like him to find some peace of their own,

even if the American Dream doesn’t provide it as easily as we may have been led

to believe.

Special Features: Audio Commentary with

Writer/Producer/Director Werner Herzog, Moderated by Norman Hill; Theatrical

Trailer

“Woyzeck” (1979)

On the special feature for “Woyzeck,” moderator Laurens

Straub defines this as the most German of Herzog’s works and the director

agrees that the infamous play by Georg Buchner is such a well-known piece of

theatre in Germany that it’s a nationally known story. It may be German lore, but

there’s something internationally common in the theme of a man abused mentally

and physically to the breaking point. Such is the story of Franz Woyzeck

(played with such a different physical presence by Kinski that one can barely

see the same actor as “Aguirre”), a terminally put-upon soldier in a German

town who, much like Kaspar Hauser, has become almost a plaything for the more

powerful people in his world. He is experimented on, mocked, and

psychologically tortured. And he cracks.

Having worked on the play many years ago, I know more about

“Woyzeck” than some, I suppose, and I found Herzog’s detached approach to the

material an intriguing filmmaking choice. “Woyzeck” is a film in which we are

more observer than participant, much like a theatre production, but that makes

it a unique entry in the Herzog oeuvre in that his films often drag us along

with the characters instead of presenting them. Consider the physical journeys

of “Aguirre” or “Fitzcarraldo.” “Woyzeck” is a mental journey that serves as

fascinating connective tissue in Herzog’s library—especially if you agree with

Straub that it’s Herzog’s last “German film” before he became an international

director—even if it’s not my favorite film in the Collection.

Special Features: In Conversation—Werner Herzog and Laurens

Straub (In German with English Subtitles); Theatrical Trailer

“Nosferatu the

Vampyre” (1979)

A film that could be called Herzog’s breakthrough is still

one of the most terrifying works of the ‘70s due to its creator’s grounded,

tactile, realistic approach to horror. There are no special effects. The

stage-setting mummies that you see under the opening credits? Yeah, they’re

real. As is the bat that follows. And Dracula’s castle. Everything is dirty,

naturally lit, genuine. Herzog has made a career of blurring the line between

reality and fiction, which is the underlying reason that Nosferatu is so

terrifying. This is not a “movie monster”; this is a monster in the real world

that we can feel, touch, smell.

At the same time, “Nosferatu” is one of Herzog’s most

visually striking films. Even within his realistic aesthetic, he finds

memorable images—the shadows of Jonathan’s journey to Borgo Pass, the entirety

of the first scene between Dracula and Harker. Watch the way that dinner is

blocked and directed. It’s a masterpiece—note how Kinski never averts his eyes

from Jonathan; he is a creature sizing up his prey like an animal who never

takes its eyes off that which could possibly threaten it.

The commentary here is one of the best as well as Herzog

explains how he had to root himself in the basic rules of the genre, something

he had never really done before. That was his “challenge” here, much like the

challenges of hypnosis in “Heart of Glass” or the conditions of shooting

“Aguirre.” The challenge of staying loyal to the source material, fulfilling

genre expectations, and yet making a film that is still distinctly Herzog’s. It

remains one of his best.

Special Features: Audio Commentary with

Writer/Producer/Director Werner Herzog; Audio Commentary with Werner Herzog,

Moderated by Lauren Straub (In German with English Subtitles); Vintage

Featurette—The Making of Nosferatu; Theatrical Trailers

“Fitzcarraldo” (1982)

“It’s only the

dreamers who move mountains.”

Arguably Herzog’s most acclaimed and popular work sits

comfortably in the center of this collection as a clear commentary on the

filmmaker himself. He is the dreamer who moves mountains. When people discuss

Herzog’s filmography, this is often the film that first comes up in

conversation. It has all the beats we’ve come to recognize from the filmmaker—from

the treacherous physical conditions of the shoot to his tumultuous relationship

with star Klaus Kinski. It is about an artist forced to action through his

passion and how that leads to disaster. It almost comments on “Aguirre” and

feels like it couldn’t exist without it.

The story of “Fitzcarraldo” is that of a rubber baron trying

to access a portion of Peru widely considered out of reach due to the rapids that

would greet anyone who tries to claim it. To do so, he has to move a 320-ton

steamboat across a relatively long, relatively hilly patch of land. To make the

film, Herzog did exactly that. The production of “Fitzcarraldo” is as notorious

as Coppola’s journey to produce “Apocalypse Now” and results in nearly as epic

of a production (157 minutes). I find it almost impossible to watch

“Fitzcarraldo” without thinking about Herzog’s other films, both previous and

the ones that would follow, that hinge on man’s relationship to the natural

world (“Grizzly Man,” “Lessons of Darkness,” “Encounters at the End of the

World”). It’s also here where Herzog would become fascinated with the natives

of Peru. His narrative interest in the uprooting and elimination of indigenous

people would begin to take form and would define a large portion of the rest of

his career. “Fitzcarraldo” may not be my favorite Herzog film, but it is

arguably the definitive one. The Collection wouldn’t be the same without it.

(And I highly recommend heading over to Hulu after watching it to check out Les

Blank’s excellent “Burden of Dreams,” which details its production.)

Special Features: Audio Commentary with Producer/Director

Werner Herzog, Producer Lucki Stipetic, Moderated by Norman Hill; Audio

Commentary with Werner Herzog, Moderated by Laurens Straub (In German with

English Subtitles); Theatrical Trailer

“Ballad of the Little

Soldier” (1984)

This 45-minute piece produced in conjunction with Herzog’s

friend Denis Reichle, a wartime photographer, is devastatingly depressing but

powerful. Still, I’m not sure it could stand as a feature, simply because it is

such an upsetting peek into a dark, dark side of the world, that in which

children are turned into soldiers. The Miskito Indians of Nicaragua used child

soldiers in their battles against the Sandinistas in the ‘80s and Reichle asked

Herzog to help him document the atrocity.

From a filmmaking standpoint, it’s fascinating how much

Herzog allows the people of this project to define its emotionally disturbing

viewpoint. What I mean is that he doesn’t use a lot of flourishes or camera

tricks or manipulative devices that would be found in many modern documentaries

about child soldiers. The words of the Miskito children and the people who have

turned them into soldiers are enough. Hearing about why children are easier to

use because they’re easier to brainwash and because “they’re the bravest,” it’s

difficult not to feel your stomach turn.

Special Features: None

“Where the Green Ants

Dream” (1984)

Herzog’s interest in displaced people continues in this unique

drama that plays as part-documentary and part-narrative. It is a relatively

straightforward story of Aborigines in Australia who are watching their way of

life disappear under the thumb of industry. It’s about a land feud, the kind

that still happens to this day around the world. Progress needs space and that

quest for land can change a very culture.

Herzog hired a number of non-actor Aborigines, but he places

them in the same context as clear actors, such as Bruce Spence, the man forced

to negotiate with the people who stand in the way of his company’s mission. The

result is a film that teeters a bit too much between styles for me. It works

best when Herzog is allowed to focus on the Aborigines, the people with whom he

clearly relates and sympathizes, but the arguably straightforward narrative of

scenes like the lengthy legal hearing that is to determine their fate feels

more staged than anything else in the Collection. It’s minor Herzog, but even minor

Herzog can be fascinating, particularly within the context of the rest of this set.

Special Features: Audio Commentary by Director Werner

Herzog; Theatrical Trailer

“Cobra Verde” (1987)

Herzog’s last film with Kinski closed a major chapter in

film history and it did so with the same passion and fury as they produced in

previous films. Some have suggested that “Cobra Verde” is itself a commentary

on the dynamic between its director and star, allowed to run wild over much of

this production but doomed in the end by its maker. This story of a man trying

to reopen the slave trade in Africa and the violent world in which he exists is

endlessly fascinating, even if it’s almost impossible to separate the film’s

subject from the people making it, which seems intentional on Herzog’s part.

At first, “Cobra Verde” feels a bit painterly and subdued

but then Kinski starts to unleash. You can feel the director giving him more

and more rope with which to play. By the end, when Cobra Verde is tied up by

Africans, his face painted black, through which he is sweating profusely, and

is screaming and spitting, it had become a film that could have been made by no

one else starring no one else. The heat, the threat of violence, the slaves who

are clearly non-actors—who is acting as the slave owner in this moment? The

director ordering them what to do? The character? Both? Neither? It is a

fascinating, ambitious piece of filmmaking. And the image of a man trying to

pull a boat out to the ocean, a boat far heavier than he could possibly move on

his own, perhaps says more about Herzog and Kinski’s dynamic of co-dependent

lunacy than any other image could.

Special Features: Audio Commentary by Director Werner

Herzog; In Conversation—Werner Herzog and Laurens Straub (In German with

English Subtitles); Theatrical Trailer

“Lessons of Darkness”

(1992)

A film that’s difficult to define as narrative or

documentary, existing mesmerizingly in the in-between, this 50-minute project

has a simple history. Herzog went to the ravaged landscape of Kuwait after the

first Gulf War and filmed what he found, turning it into a perfect companion to

“Fata Morgana,” although this film feels more melancholic and desperate. It’s

not just the similar fascination with the natural world that links “Morgana”

and “Lessons,” but also the sense of how man has forever impacted nature in

irreversible ways.

Herzog trains his camera on striking, unforgettable images

like fields covered in oil and fires raging to the sky. There are moments, like

in “Morgana,” where it is difficult to discern exactly what one is looking

at—debris, charred landscapes, a complete lack of humanity. These images look

like a post-apocalyptic Hollywood production but they’re not. It’s one of

Herzog’s most visually striking films to this day. Both captivating and

unforgettable.

Special Features: None.

“Little Dieter Needs

to Fly” (1997)

Herzog’s fascination with people who have lived existences

to which we can barely relate reaches one of its most interesting subjects in

Dieter Dengler, a German-American Navy pilot who was shot down over Laos and

taken prisoner for two years, during which he was brutally tortured. (Herzog

would tell Dengler’s story again several years later in “Rescue Dawn” with

Christian Bale and Steve Zahn.) Herzog makes the very interesting decision to

take Dengler back to Laos and Thailand to convey his story. It makes for a

production very different from what it would be if Dengler merely sat in a

chair for an interview. It feels tactile and even dangerous.

The first words spoken by Herzog in the film’s narration are

“Men are often haunted.” Is he

speaking of Dieter or himself? Or Aguirre? Or Fitzcarraldo? Or Cobra Verde? At

this point in the Collection, it’s clear to even the most casual viewer how

much Herzog’s own ghosts have influenced the entire set.

Special Features: None.

“My Best Fiend”

(1999)

The last film in “Herzog: The Collection” almost plays like

a special feature in and of itself in that it’s the behind-the-scenes

examination of Herzog’s relationship to Kinski, the star of five films in the

set. I find “Burden of Dreams” a more interesting behind-the-scenes documentary

but it’s a distinctly different film. Whereas that was produced by a third party

(Les Blank), this film is clearly Herzog’s story to tell. He’s often on-camera

when he does so, making him the active subject of the film as much as Kinski. Which

feels appropriate because, in true to form fashion, he’d never let Kinski take

too much of the stage.

Special Features: Theatrical Trailer

If this set or even just this piece about it has

inspired you to see more Herzog, there are dozens more works to consider,

including his first film, “Signs of Life,” and recent acclaimed works such as

“The Wild Blue Yonder,” “Rescue Dawn,” “Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New

Orleans,” “The White Diamond,” “Grizzly Man,” “Encounters at the End of the

World,” “Cave of Forgotten Dreams,” and “Into the Abyss.” And click here to read more about Herzog’s films through Roger’s reviews.