Good

gravy, can it really be true? Has it really been nine years since the passing

of Robert Altman, one of the best and most idiosyncratic of all American

filmmakers? Nine years since the release of one of those films that, depending

on one’s point of view, amused, outraged, inspired or perplexed audiences and

critics alike—all at once, in many cases?

Nine years since the time when one could purchase a ticket for his latest work

and feel confident that, regardless of whether it was “good” or

“bad,” they were about to experience a genuinely singular cinematic

experience? On the one hand, it doesn’t feel that long because the films

themselves are so vibrant and alive (and often ahead of their times) that they still

feel more fresh and vital than most current movies. On the other, the absence

of that vitality can be felt more and more with each passing year, as even the

more artistically inclined films have begun to fall into a depressingly rigid

lockstep that even his dopiest efforts usually managed to avoid—he may have made the occasional bad movie but he almost

never made a boring one.

Whether a

conscious effort to mark the anniversary of his passing or the result of the

kind of unconscious cosmic synergy that often cropped up in his work, a number

of Altman’s films are making their long-awaited Blu-ray debuts—Kino Lorber is issuing “The Long

Goodbye” (1973), “Thieves Like

Us” (1974) and “Buffalo Bill

& the Indians or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson” (1976), while

Olive Films is offering up “Come Back to

the 5 and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean” (1982). On the surface, none

of these films may have the immediate cachet of such better-known Altman titles

as “MASH” (1970), “Nashville” (1975) or “The

Player” (1992), but in terms of style, character and iconoclastic charm,

they are all more than worthy works from one of the all-time great filmmakers

and they all play just as well today as they did when they first came out—even better in some cases. Put it this way—having seen the vast majority of this year’s Oscar derby

competitors at this point, I would cheerfully rank all four of these titles

above the vast majority of the current awards competition without even the

slightest hesitation.

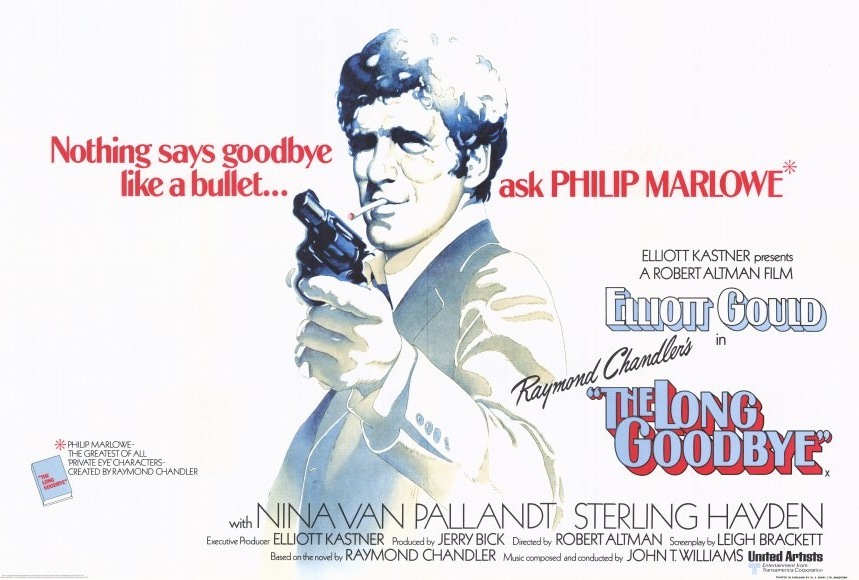

Based on

the 1953 novel by Raymond Chandler featuring his beloved hard-boiled detective

character Philip Marlowe, “The Long Goodbye” found Altman taking a

stab at the private eye genre but anyone looking at it for a standard-issue

whodunnit is likely to be as perplexed as those who went into “McCabe

& Mrs. Miller” expecting a typical western. Instead of the tough,

laconic version of Marlowe embodied by the likes of Humphrey Bogart, this

version presented viewers with Elliott Gould as a constantly muttering goof

who helps an old friend cross the border into Tijuana, learns that the

now-vanished friend has been accused of murdering his wife, and attempts to get

to the bottom of what really happened in an investigation that finds him

crossing paths with an angry gangster (Mark Rydell), a quack doctor (Henry

Gibson), a drunken author (Sterling Hayden) and the author’s beautiful blonde

wife (Nina Van Pallandt). Throughout his shambling inquiries, Marlowe is

treated with disdain by practically everyone he encounters—even his pet cat

runs out on him when he commits the unpardonable sin of not purchasing the

right food—but what they fail to recognize is that, unlike most members of the

Me Generation, he has a certain personal code that still

upholds such outdated notions as friendship and loyalty, and woe to anyone who

violates it.

Although

the screenplay to “The Long Goodbye” (penned by Leigh Brackett, who

previously co-wrote the classic “The Big Sleep”) is as solidly

constructed as one could hope, Altman uses it as a springboard for a

one-of-a-kind narrative that pokes fun at the private eye genre without

completely crossing the line into outright parody, while maintaining a serious

undertone that only becomes fully evident when it is all over and one finally

realizes that this Marlowe is not to be trifled with. Although Gould may not be anyone’s immediate

idea of Philip Marlowe, his out-of-place nature underscores the notion that the

character and the ideals that he once represented are themselves now out of

step in a era of drugs, free love and self-improvement. The film also contains

two of the most jarring moments of Altman’s entire career—one in which the

gangster (whose minions include a then-unknown Arnold Schwarzenegger) shatters

a Coke bottle against the face of his girlfriend in order to prove his

seriousness to Marlowe, and the finale in which Marlowe faces

the ultimate betrayal and responds in kind.

Needless to say, this was considerably

different from what most fans of Chandler were expecting and, as would prove to

be the case a few years later when he subverted long-held notions of an equally

iconic character in his screen adaptation of “Popeye,” the film

outraged many viewers and critics at the time. As it turned out, also like

“Popeye,” his idiosyncratic approach would wind up gaining enormous

favor in subsequent years to a point where “The Long Goodbye” is now

often cited as one of his great works. It would also prove to be one of the

more influential ones as well. The shaggy dog approach to the storyline and the

collection of colorful characters, each of whom could plausibly inspire their

own film, would prove to be a key influence on the Coen Brothers when they made

their own riff on the genre in the cult favorite “The Big Lebowski.”

More recently, while Paul Thomas Anderson’s brilliant “Inherent Vice”

is, first and foremost, a highly effective adaptation of the singular prose

stylings of Thomas Pynchon, traces of “The Long Goodbye” can be found

in its DNA.

Based on

the Edward Anderson novel that would inspire the Nicholas Ray film “They

Live By Night” (1949), “Thieves Like Us” is a Depression-era

crime drama/lovers-on-the-run saga that begins with three convicts—Bowie

(Keith Carradine), T-Dub (Bert Remsen) and Chicamaw (John Schuck)—escaping

from prison and executing a series of robberies while holed up in a farmhouse

along with Dee Mobley (Tom Skerrit) and the naive, Coke-swilling romantic

Keechie (Shelley Duvall). After one robbery goes violently wrong, the group

splits up, but when Bowie is injured in a car accident, he returns to the

farmhouse and is nursed back to health by Keechie. During his convalescence,

Bowie and Keechie fall in love and idly speculate about somehow making a life

for themselves free of crime. It isn’t to be, of course, and after half-hearted

stabs at loyalty (springing Chicamaw from jail) and morality (cutting Chicamaw

loose rather than get sucked back into his old life), Bowie meets his

inevitable fate.

Produced

amidst a flurry of activity from Altman that would culminate the next year with

the arrival of “Nashville,” “Thieves Like Us” is one of

those titles that has always tended to get lost in the shuffle, and while it may

be one of his smaller films in that it does not contain the sprawling

narratives or cast of his more expansive works, it is nevertheless fairly epic

on an emotional scale. Rather than focus on the criminal activities and their

violent aftermaths in the manner of the superficially similar “Bonnie

& Clyde” (whose infamously choreographed scenes of bloodshed are

diametrically opposite to the short and brief bursts of brutality displayed

here), Altman is more interested in presenting viewers with a character piece

centered around the short, sweet and ultimately doomed relationship between

Bowie and Keetchie that is aided greatly by the touching performances from

Carradine and Duvall.

At the

same time, the film also serves as an intriguing look at male aggression and

its ultimate failings, a theme that would crop up in many of his films over the

year—the men may have the guns and the booze and the bluster but they are

little more than slaves to their own desires while it is the women, especially

T-Dub’s in-law Mattie (Louise Fletcher) that ultimately prove to be smarter and

more capable at doing what it takes to survive. Another nice and occasionally

ironic touch comes from Altman’s decision to eschew a traditional score in

order to set all the action to what is playing on the radio, anything from

music to old radio programs that inevitably wind up commenting on the action.

(During a romantic interlude between the two lovers, a production of

“Romeo & Juliet” can be heard in the background.) “Thieves

Like Us” may lack the galvanizing effect of some of Altman’s better-known

films but in its own quietly moving way, it is as powerful as anything that he

ever did and is a film ripe for rediscovery.

In the

wake of the success of his next film, “Nashville,” all eyes were on

Altman to see what he would come up with next and as a result, it was perhaps

inevitable that this followup, “Buffalo Bill & the Indians, or Sitting

Bull’s History Lesson,” would prove to be arguably his highest-profile

flop to date. On paper, it all sounded so promising—loosely adapted from

Arthur Kopit’s play “Indians” by key Altman collaborator Alan

Rudolph, the film was a savagely satirical revisionist western in which Buffalo

Bill Cody (Paul Newman), now running a ramshackle revue that purports to tell

the “real” story of how the west was won, scores what he thinks is an

enormous publicity coup by hiring no less of a figure than Sitting Bull (Frank

Kaquitts), the defeater of Custer himself, to appear. Much to his frustration,

his new attraction fails to live up to the racist cliches about the savage

Indians that his show has continued to perpetrate—this Sitting Bull is, unlike

Cody, quiet, decent and morally correct in all regards as he silently observes

the perversions of the historical record that the show is based upon. Things

come to a head when Sitting Bull, through his emissary (Will Sampson), not only

refuses to participate in Cody’s take on Custer’s defeat (the result of a

cowardly sneak attack) but insists that the show perform a recreation of a U.S.

military massacre on a peaceful Sioux village—Cody angrily fires him in

response but then finds himself in a bind when the show’s star attraction,

Annie Oakley (Geraldine Chaplin), sides with Sitting Bull and refuses to

perform as well.

It is

generally assumed that since the film happened to be released at the height of

Bicentennial fever during the summer of 1976, the dark and cynical satire that

it trafficked in instead of the patriotic romp promised by the ads no doubt

contributed to its commercial and critical failure (which also led to a

falling-out with producer Dino De Laurentiis that cost Altman the chance to

make his long-cherished adaptation of E.L. Doctorow’s novel

“Ragtime“—by blending the historical and the fictional together as

he did here, Altman almost appeared to be using “Buffalo Bill” as a test

run for ideas to use for that never-to-be project). This is perhaps not too

surprising, but what is odd is that people have not gone back in subsequent

years to take another look at it because, stripped of the ridiculous

expectations that accompanied its original release, the film is both enormously

entertaining and thought-provoking in equal measure. Instead of simply making

fun of America, as was the charge at the time, Altman is instead drawing

fascinating parallels between American history and showbiz history and how both

are perfectly willing to massage, revise or outright stretch the truth in order

to tell a better story. (If one reads

Bill’s revue as a form of Hollywood before the existence of Hollywood, then the

film would make for a fascinating double-bill with his equally dark showbiz

satire “The Player.”)

This is never funnier nor sadder than in the

case of Cody himself, a legitimate war hero who, as seen here, became so

obsessed with burnishing his own legend by the most questionable of means that

not even he was able to distinguish the truth from the horseshit that he

cheerfully slings to the masses. This is beautifully conveyed through Newman’s

wonderful performance, one of the most underrated of his career in the way that

he depicts Cody with all the charm and bluster one could hope for along with a

subtle undercurrent that quietly suggests that even he recognizes that behind the

elaborate facade is a guy who drinks too much, can no longer shoot straight and

is forced to wear a wig in public to keep up appearances regarding his

virility. In a perverse way, he even admires Sitting Bull for maintaining the

authenticity that he threw away long ago for fame and glory. Frankly, this is

more interesting than any bicentennial snarking that would have become dated a

few months after its release—its notions are as timely and relevant as ever

and as a result, the film as whole has a freshness and vitality to it that is

both surprising and surprisingly engaging.

After a

few years of commercial non-starters that culminated with his

still-controversial adaption of “Popeye,” which was criticized for

being weird, taking too many liberties with the material and not making as much

money at the box-office as “Star Wars” or “Superman,”

Hollywood decided that it had no more use for a maverick fiilmmaker like

Altman. Coincidentally, Altman felt pretty much the same way, but, instead of

simply licking his wounds, he went off into a wholly unexpected area by

spending the next few years filming a series of low-budget adaptations of stage

plays. This period kicked off with the last film covered here, “Come Back

to the 5 & Dime Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean,” Ed Graczyk’s play about a

group of women from a small Texas town united by their adoration for James Dean

whose reunion twenty years after his death exposes any number of secrets and

resentments that have built up over that time. Having staged the play in New York

with a cast made up of familiar faces (Sandy Dennis and Karen Black), relative

unknowns (Kathy Bates) and one major wild card in pop icon Cher making her

dramatic debut.

Truth be

told, the screenplay (adapted by Graczyk himself) is perhaps the least

interesting aspect of the enterprise—it is a little too gimmicky in certain

places and some of the shocking revelations are anything but. However, what

makes it work is the way that Altman translates the material from the stage to

the screen in a way that honors its stage origins while still making it into a

true cinematic experience. Having worked with such broad canvases over the

previous decade, he nevertheless showed a surprising facility for working on a

more intimate scale without overwhelming the material. The film also allows him

to deal with one of his favorite subjects—women. Over the years, Altman has

always shown a fascination for dealing with women and the things they do to

cope and survive on a daily basis and while his matter-of-fact depiction of the

cruelties they sometimes face has occasionally led to charges of misogyny, his

work, especially here, gives lie to that particular accusation. Working with an

all-female cast (save for Mark Patton), he gives them all chances to shine and

they all tear gleefully into the material and the chance to play characters

instead of appendages. As for whatever intuition led him to cast Cher, a move

that inspired no small amount of derision when it was announced, it was an

inspired move because she delivers a strong performance that is utterly free of

the camp persona she had developed over the previous decade and which

single-handedly launched her career as a serious actress.

The four Blu-rays contain some special features

but how special they are will vary from person to person. The three Kino Lorber

discs were licensed from MGM, who put them out on DVD, and they have ported

over the extras from those releases without adding anything new to the picture

beyond the HD transfers. While the lack of new stuff is a bit of a bummer, the

old stuff is pretty good—”The Long Goodbye” features an interview

with Altman and Gould about the project and another interview with famed

cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond in which he discusses the unique approach that he

took in shooting the film, which is also the subject of a reprinted

“American Cinematographer” article from 1973. “Thieves Like

Us” contain a full commentary track with Altman that is a fascinating

listen. “Buffalo Bill,” alas, has nothing to show for it beyond a trailer.

As for “Jimmy Dean,” which is making its DVD/Blu-ray debut after

years in the home video wilderness, it contains an interview with Graczyk in

which he talks about working with Altman and the odd journey that his play took

on its way to the stage and screen. However, these are films that hardly need a

bunch of flashy extras to help further one’s appreciation of them—a simple

spin of the movies themselves will not only do that but will presumably inspire

viewers to watch (or hopefully rewatch) the works of one of the all-time

greats.