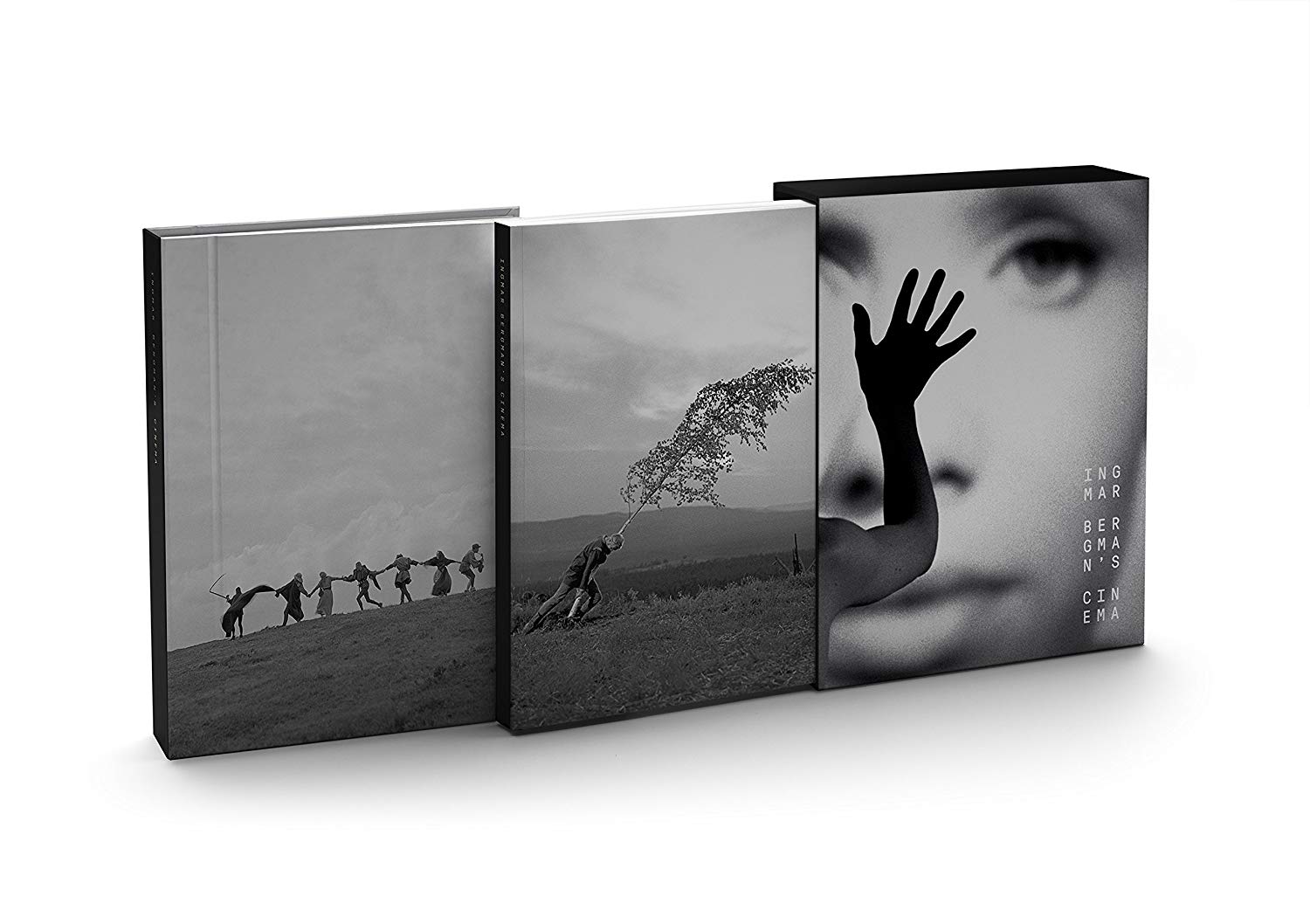

I’ve struggled with how to start writing about Criterion’s release of “Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema.” How does one begin to wrap their arms around the career of a master? And, make no mistake, this is a career-defining release, including 39 of Bergman’s films along with hours and hours of special features and a 240-page book full of essays. Where do you start? As a lifelong film fan and critic for two decades, I’ve been exposed to the most notable Bergman movies, of course, but even the works I had seen feel somehow different in this release, placed in a new context of a remarkable career. Honestly, I wasn’t even sure how to digest it much less write about it.

Sure, the logical thing may be to take in the films you haven’t seen first, but it’s sure tempting to revisit favorites with new transfers—and every Bergman movie has been a bit different for me depending on my stage of life. The truth is that I watched most of them when I was a young, blooming cinephile. To say that something like “Winter Light” plays differently in my 40s than it did in my teens would be a massive understatement. It’s almost as if I had never seen it until this set. This is the kind of release that works even if you’ve seen most of the films within it, as Bergman changes as we do.

One way to experience “Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema” would be to let it unfold in the unique manner that Criterion has assembled it. The 39 films are not ordered chronologically, organized instead in the manner of a film festival. What that means is there’s a “big” Opening Night film in the crowd-pleasing “Smiles of a Summer Night,” but then the second disc includes rarer Bergman films from the previous decade, “Crisis” and “A Ship to India.” A few discs later, in the manner of a film festival, there’s a ‘Centerpiece’ two-disc affair in which you could watch both versions of “Scenes from a Marriage” and Bergman’s last film, “Saraband.” The thematic connection caused by including those two films, made three decades apart, on one disc is a fascinating one, the kind of thing that could spark a discussion group.

The Bergman festival continues with a trio of consecutive discs that’s not labeled as a Centerpiece but could easily be watched in one day—“Through a Glass Darkly,” “Winter Light,” and “The Silence.” Seeing these films before “The Seventh Seal” (Centerpiece 2, of course) and after “Saraband” creates an interesting new way to examine Bergman’s career, segmented in thematic ways instead of merely chronological ones.

Centerpiece 3 is “Persona,” one of the most daring and influential films of all time, and the set’s Closing Night presentation is a two-disc release of “Fanny and Alexander,” starting with the 320-minute TV version and ending with the theatrical one. Given that Bergman once said this autobiographical film would be his last, it’s a perfect fit for the closing chapter. In between the “Greatest Hits,” you’ll find dozens of lesser known films, many of them never available on Blu-ray before. Given a lot of these films were already on Criterion-issued Blu-rays, films like 1968’s “Shame” or 1970’s documentary “Faro Document” may be the biggest draw for cinephiles.

To be upfront, I did not follow the festival formatting of the set. I was too eager to get to films I hadn’t seen in a long time like “Winter Light” and films I had never seen like “The Magician.” So I bounced around. And I realized in doing so that this is a box set that will not merely take up space on my shelf but be a cinematic gift I return to regularly, dipping in and experiencing a Bergman movie whenever I’m in the mood. It’s more of a library than a box set, a reference guide to a century of influential filmmaking. And watching some or all of a dozen films, I was struck by something friend and colleague Glenn Kenny said to me via email when he mentioned how Bergman always has a reputation of being intimidating but that his films are more accessible than people believe. It’s undeniably true. The deeply symbolic register of Bergman became parodied but he’s also one of our most relatably human directors. Who couldn’t relate to the crisis of faith in “Winter Light” or the family issues of “Fanny and Alexander”? And people often under-appreciate his “lighter” films like “Smiles” or “The Magician,” both far from intimidating.

The films themselves are the big draw here, but the special features are overwhelming for people who really want to dig in. Several of the discs contain feature-length documentaries, such as 1998’s “Ingmar Bergman on Life and Work” (on “Wild Strawberries”), 1963’s “Ingmar Bergman Makes a Movie” (on “Winter Light”), 2006’s “Bergman Island” (on “The Seventh Seal”), and 2012’s “Liv & Ingmar” (on “Persona”). There are dozens of interviews and featurettes and other supplemental material. It’s almost too much.

Finally, my time with “Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema” brought me back to something truly wonderful, Roger Ebert’s writing about it. Some highlights:

From his Great Movie entry on “The Seventh Seal”:

Bergman’s work has an arc. The dissatisfied young man considers social and political issues. In middle age, he asks enormous questions about God and existence. In old age, he turns to his memories for what answers there are. And in many of these films, there is the same kind of scene of reconciliation. In “The Seventh Seal,” facing the end of his own life and the general destruction of the plague, the knight spends some time with Joseph and Mary and their child, and says, “I will remember this hour of peace. The dusk, the bowl of wild strawberries, the bowl of milk, Joseph with his lute.” Saving this family from Death becomes his last gesture of affirmation. In “Cries and Whispers,” a journal left by the dead sister recalls a day when she was feeling a little better, and the sisters and a maid walked in the sunlight and sat in a swing on the lawn: “I feel a great gratitude to my life,” she wrote, “which gives me so much.”

On the visual approach to “Winter Light”:

The film’s visual style is one of rigorous simplicity. Nykvist does not use a single camera movement for effect. He only wants to regard, to show. His compositions, while sometimes dramatic, are mostly static. He uses slow push-ins and pull-outs to underline dialogue of intensity. His gaze is so unblinking that sequences with the potential to be boring, like the opening scenes of the consecration and distribution of hosts and wine, become fascinating: More is going on here than ritual, and there are buried currents between the communicants. Nykvist focuses above all on faces, in closeup and medium shot, and they are even the real subject of longer shots, recalling Bergman’s belief that the human face is the most fascinating study for the cinema.

On “Persona”:

“Persona” (1966) is a film we return to over the years, for the beauty of its images and because we hope to understand its mysteries. It is apparently not a difficult film: Everything that happens is perfectly clear, and even the dream sequences are clear–as dreams. But it suggests buried truths, and we despair of finding them. “Persona” was one of the first movies I reviewed, in 1967. I did not think I understood it. A third of a century later I know most of what I am ever likely to know about films, and I think I understand that the best approach to “Persona” is a literal one.

Read more here and get your copy of “Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema” here.