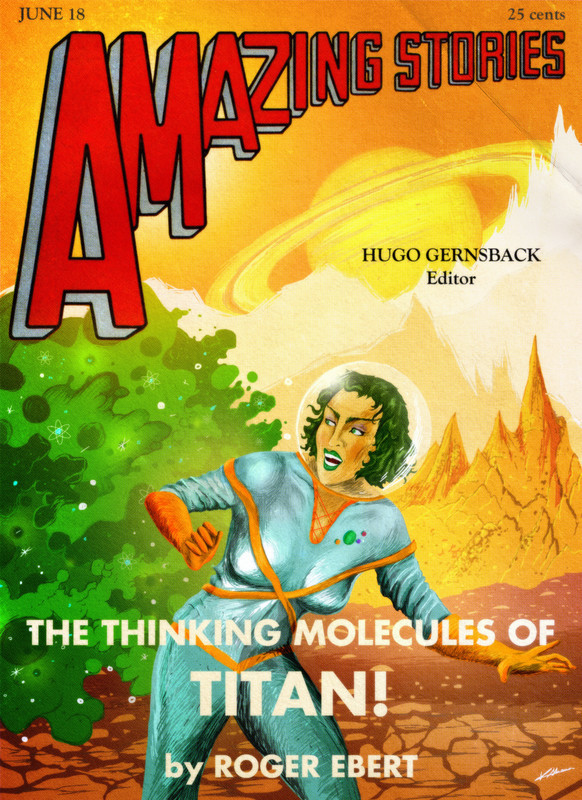

In honor of World UFO Day we are reprinting Roger’s unfinished science fiction story about a phenomenon on Saturn’s moon, Titan. In 2013, I invited readers to write an ending to Roger’s tale and we got so many good ones that I asked our Far Flung Correspondent Krishna Shenoi to illustrate all of the finalists. They are also being reprinted today in a separate Table of Contents on this website. Please note that the version of Roger’s short story printed below is slightly altered in that it contains a couple of sentences added from a second version he wrote. — Chaz

The story so far:

he text message came as Mason was dipping fried lake perch into the tartar sauce. This was in the Capital, Campustown bar that offered an elementary but cheap menu, on the grounds — the owner McHugh once told him — that if someone left looking for food they might never come back. The message on Mason’s phone said, We have a pattern. He reflected that any pattern by definition would be untold years in age and would not change now that the Titan Listening Lab had recorded it. He finished his perch, his French fries and his canned creamed corn. He closed with Apple Crumb Cake and the last of his beer. He said goodbye to his friends Alex and Claire.

“Later,” Alex said. Claire may possibly have nodded. They were leaning over shoeboxes filled with punch cards, part of their project to rebuild a museum working model of PLATO, the old computer program created on the Illinois campus in the 1960s. The Capital was a vaguely bohemian place surrounded by disgusting undergraduate hangouts where underage students drank illegal beers. This in Mason’s opinion was the upside of their lamentable tendency to stand outside and lean over the sidewalk to vomit.

He walked east on Green Street, noted as he always did that Alma Mater was still standing, and turned left at the College of Engineering to walk down to the National Center for Supercomputer Applications. During this walk the fauna shaded from barfing Greeks to distracted Geeks. His measured steps were intended to contain any sign of eagerness. He wasn’t falling for this pattern. Mason had been listening to Titan—or rather his equipment had been listening—for so long he knew that if he betrayed hope the moon would break his heart. He knew that this pattern, like all promising patterns in celestial noise, was very unlikely to be a message. There would be some mundane way to explain it away, and no reason to anticipate it was being sent from, or to, any entity, for any reason.

Mason’s primary reason for monitoring the signals was an admirable one: It brought in grant money. The University was a subcontractor tuned in to the Cassini spacecraft since it launched in 1997. Cassini represented primitive technology by today’s standards, and yet it was heading where man’s mind had never been before, and would send back signals when before there had been only silence. For long cold years it moved doggedly through the solar system, finally arriving in an orbit around Saturn. Then numbers fell into place in its onboard computer and unthinkingly Cassini gave birth to its passenger, a lunar lander named Huygens, which landed on Titan in 2005. Not much had happened since.

Titan is a curious resident of the Solar System. For that matter, Mason reflected, it was curious that it existed at all, and for that matter it was curious that Saturn existed at all, and the Universe at all, and Mason at all. He found it a consolation to contemplate how small he was, in comparison to his surroundings. When had it been, that day he switched over from imagining the universe beginning with Earth and extending beyond? One day he found that his point of view was no longer in Urbana, Illinois, and was now located in some undefined, implacable immensity where all the Universe was a pinpoint of light, and in his imagination he approached it through the void until it broke down intimately into larger pinpoints, and then galaxies, suns and planets, like in one of those You Tube speed-up videos. Closer and closer Mason would draw in his mind, until finally he was in Urbana, and Alma Mater was standing with arms outstretched.

ason’s step had quickened, he noticed. In density, Titan was half ice, half rock. If only she had known this, Emily Dickinson would have written a poem about it. Since ice and rock tend in their nature to remain ice and rock, what interested Mason was an ocean of magma between the ice and the rock. This sort of sea was not frozen because it contained a great deal of ammonia. If anything was happening on Titan it was happening there, thought Mason as he used his swipe-card to pass Security and take the elevator to the floor where his laboratory was located. Swipe cards were made possible because of early computer programs such as those at Illinois. At the time, the university’s’ computer department was contained entirely within a modest office building just east of what was now the Center. It was filled mostly with vacuum tubes. A photo of it was framed on the elevator wall.

“Same old same old,” said Bruce Elliott, who was on duty in the lab. “Maybe an undertone of a slight variation of same old same old. Then suddenly the shit hits the fan.” Having obviously prepared his punch line, Elliott turned up a knob and the room was filled with meaningless noise. Only his computers could notice that it wasn’t quite the same. That it was old was a given.

“Your good friend Regan has a theory,” he said, referring to a woman who now took off her headphones and wheeled her chair around to face them. Her jolly red glass frames usually looked bookended by Bose.

“I have a theory,” Regan said, “but it’s impossible in practice.”

“All theories are,” Mason said, “until they’re proven to the satisfaction of every last fanatic who remains unsatisfied.”

“Well, to begin with, this sounds like a pattern. Highly unscientific, but I’ve been listening to this shit longer than you have. My theory,” Regan said, “is that we are receiving the signal from a slightly different point in the area than before.”

“We know that Cassini parachuted to the surface, which is definitely a place, and it stayed where it landed,” Mason said, “because how did it move?”

“That I don’t know,” Regan said. “It would tend to impossible.”

She giggled. Regan giggled about imponderables a lot.

“I’ve run some analysis,” she said, “and it’s clear from the machines that the class of noise we’re been receiving is subtly different.”

“How different?”

“Subtly different.”

“I see,” Mason.

“Science fiction different,” Regan said.

“Tell us a story,” said Elliott.

“Let’s go over to the Capitol,” Regan said. “I know you’ve just come from there.”

Alex and Claire were still there. “Hiya pards,” Alex said.

“Regan has a science fiction story for us,” Mason said.

Claire continued to sort her shoeboxes. Alex nodded beer to the waitress.

“In an infinitesimal solar system in a speck of a galaxy,” Regan said, “the third rock from the Sun is inhabited by intelligent beings. These creatures develop intelligence, and send a spacecraft to the moon of one of the other planets.”

“Are you racing through this?” said Alex.

“Now it gets good. This moon has a frozen surface. Beneath that surface is a magma of liquid—an ocean that encloses the moon. Apparently, the Third Rock people speculate, this ocean is somewhat made of liquid water.”

“The spacecraft went for a sail,” Alex said.

“The spacecraft was not very heavy,” Regan said. “It happened to land at a place where the subsurface sea was slightly closer to the surface, or the surface was slightly depressed.”

“Captured by pirates,” said Elliott.

“I’m ignoring you,” Regan said, and giggled. “The way they later figure it out, over several decades the spacecraft settles into the surface just a tiny wee bit. Maybe its batteries generate enough heat to melt the surface slightly.”

“You don’t even know if it has batteries,” Alex said.

“Shut up. I don’t need to know. In this ocean, life has evolved. These magma oceans were warmer than the rest of the moon. They were made up of methane-euthane kinds of shit. We know on earth that life is possible without oxygen. Think of those plumes at the bottom of the Pacific, living off sulphur. Oy, what a life.”

“I give you the plumes,” Alex said. He pushed aside his shoebox and picked up his beer.

these vast oceans, over many, many years, life evolves. I don’t think it had very much else to do. It has lots longer than seven days and seven nights. It doesn’t form bodies and evolve into plants and animals. But as Darwin taught us, a random, accidental event could cause something to change in this life, whatever it was, no matter if it was only a molecule wandering lonely as a cloud. It probably will not. It will take an untold amount of time. Countless failures. This something happened. Years pass. Two molecules get chummy and do something to react to the presence of each other.”

“They become Moby Dick,” Alex said.

“In your dreams,” Regan said, “Not enough organization. All still molecules. They lord it over their atoms. Evolving, evolving, evolving, all the way down, like the turtles.”

“I like the turtles,” Mason said. “The American Indians said they stood for perseverance.”

“Name me a culture that doesn’t say that,” Alex said.

“Okay,” Regan said, “here comes the Darwinian thunderbolt. The accident, the mutation, we don’t know what—but there must have been something, because in the result is the proof.”

“An act of God,” said Alex, needling Regan. He knew Regan was a Unitarian and so would both reject God and maintain an open mind in the subject.

“No need for God,” Regan said. “Just something. You have a change, you have a reason for a change. Not even a reason. Just the fact that first they’re this and then they’re that, which maybe happened by itself and maybe didn’t, but one way or another.”

The waitress knew them and stopped at their booth.

“One left of the apple crumb cake,” she said.

“Dibbies,” said Regan. “So anyway, we know the evolution of life involves the communication of information. Not information like the Unicops keep on potheads. Information like, here it is, and now it’s over there, and what do you know.”

“I’m with you,” Mason said.

“This is a vague idea,” said Regan. “I’m still working on it. Titan evolves molecules that group in such a way that they, oh, get together, like, and don’t actually communicate, like, but prowl around in non-self-conscious collective information patterns. That’s what we’re hearing, now that we’re closer to the source.”

“There’s only one way this is going,” Alex said. “A lunar intelligence.”

“Intelligence is not required,” Regan said. “All that’s needed are patterns that move more readily than other patterns. Patterns that lend themselves to pattern-originators. The way of least resistance. We don’t like sulphur, but it’s yummy for the deep sea plumes.”

“The Thinking Molecules of Titan,” Mason said. “I see a cover of Amazing Stories from the Gernsback era. A space girl with her head in a goldfish bowl wearing a space suit with a plunging neckline, and fleeing toward us from giant globes filled with those tiny atoms.”

“Now finish my story,” Regan said. “Over and over, one eon after another, the molecules develop a pattern that’s a good fit. It’s easy for them. It would be more difficult to stray from it. What is it?”

“It can’t be language,” Mason said. “Must be mathematical, if it’s information at all.”

“You made this all up out of thin air,” Alex said.

“Of course I did. Now you tell me what I made up after we find a way to crack those patterns.”

Claire closed her shoebox. “It’s music,” she said. They’d forgotten she was there. “The molecules don’t know it. The molecules know bupkis about notes, rhythm, orchestras or singers. It has no interest in how its pattern could take shape in the world, because it doesn’t know about worlds. It just evolves and evolves until it gets in the groove.”

The others studied their beers.

“Let me hear a little,” Claire said. Mason handed her his iPhone. She put it to her ear.

“Huh.” Claire said, “In a kitty-cornered and cold sort of way, it makes me think a little of a failed Mozart.”

Claire continued, “Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon, and for the rest of your life, you’ll crack the code, and Titan will be playing ‘As Time Goes By.’ ”