To celebrate this site’s co-founder, Roger Ebert, we are publishing some of his invaluable lists ranking the Top Ten films from particular years over the past half-century. Today is his list of the Top Ten Films of the 1990’s and you won’t be disappointed…

Click on the title of each film, and you will be directed to the full review…

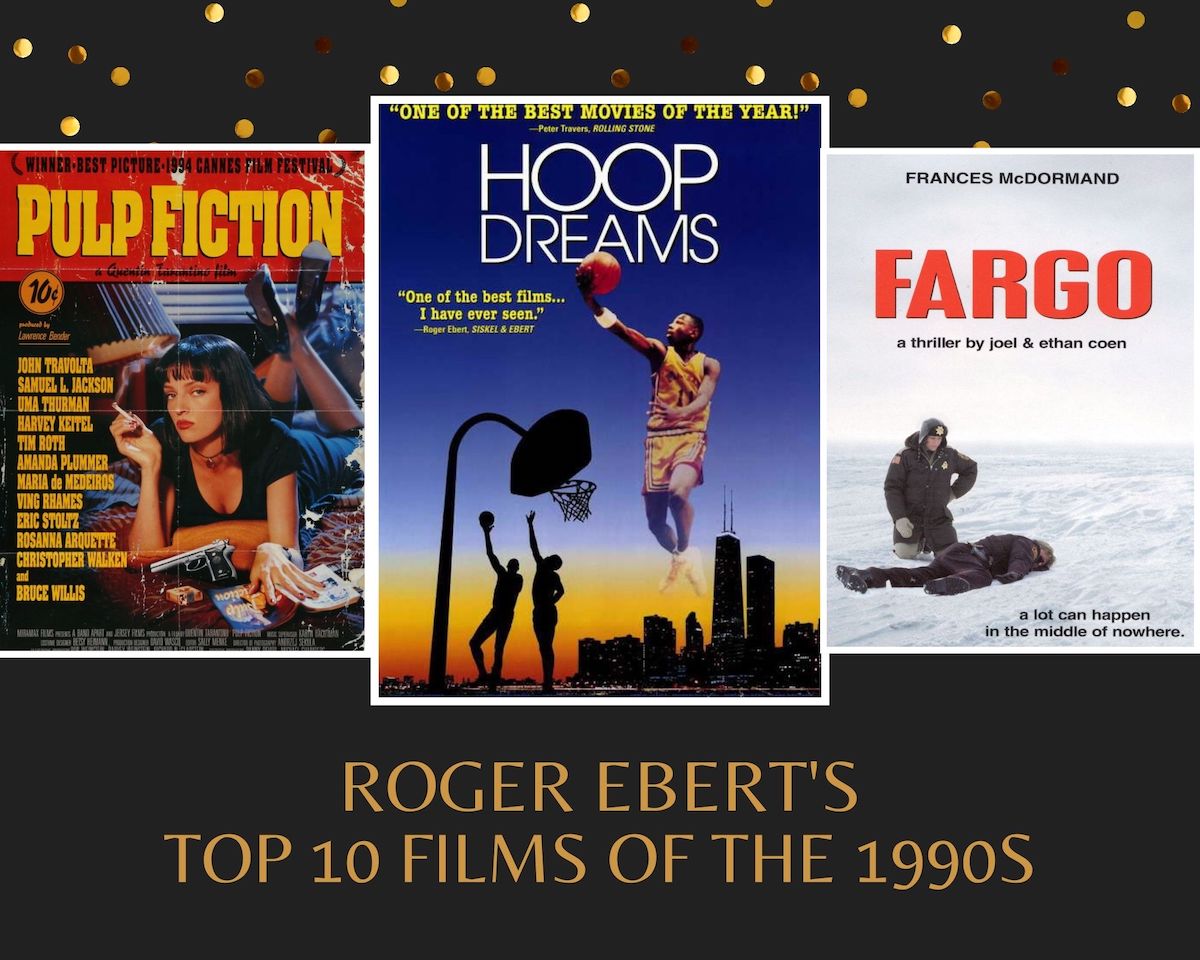

ROGER EBERT’S TOP TEN FILMS OF THE 1990s

10. JFK

Stone’s film is hypnotically watchable. Leaving aside all of its drama and emotion, it is a masterpiece of film assembly. The writing, the editing, the music, the photography, are all used here in a film of enormous complexity, to weave a persuasive tapestry out of an overwhelming mountain of evidence and testimony. Film students will examine this film in wonder in the years to come, astonished at how much information it contains, how many characters, how many interlocking flashbacks, what skillful interweaving of documentary and fictional footage. The film hurtles for 188 minutes through a sea of information and conjecture, and never falters and never confuses us.

9. MALCOLM X

Black viewers will not be surprised by Malcolm’s experiences and the racism he lived through, but they may be surprised to find that he was less one-dimensional than his image, that he was capable of self-criticism and was developing his ideas right up until the day he died. Spike Lee is not only one of the best filmmakers in America, but one of the most crucially important, because his films address the central subject of race. He doesn’t use sentimentality or political cliches, but shows how his characters live, and why. Empathy has been in short supply in our nation recently. Our leaders are quick to congratulate us on our own feelings, slow to ask us to wonder how others feel. But maybe times are changing. Every Lee film is an exercise in empathy. He is not interested in congratulating the black people in his audience, or condemning the white ones. He puts human beings on the screen, and asks his audience to walk a little while in their shoes.

8. LEAVING LAS VEGAS

The movie works as a love story, but really romance is not the point here, any more than sex is. The story is about two wounded, desperate, marginal people, and how they create for each other a measure of grace. One scene after another finds the right note. If there are two unplayable roles in the stock repertory, they are the drunk and the whore with a heart of gold. Cage and Shue make these cliches into unforgettable people. Cage’s drunkenness is inspired in part by a performance he studied, Albert Finney’s alcoholic consul in “Under the Volcano.” You sense an observant intelligence peering from inside the drunken man, seeing everything, clearly and sadly.

7. BREAKING THE WAVES

The film contains many surprising revelations, including a cosmic one at the end, which I will leave you to discover for yourself. It has the kind of raw power, the kind of unshielded regard for the force of good and evil in the world that we want to shy away from. It is easier sometimes to wrap ourselves in sentiment and pious platitudes, and forget that God created nature “bloody in tooth and nail.” Bess does not have our ability to rationalize and evade, and fearlessly offers herself to God as she understands him. This performance by Emily Watson reminds me of what Truffaut said about James Dean, that as an actor he was more like an animal than a man, proceeding according to instinct instead of thought and calculation. It is not a grim performance and is often touched by humor and delight, which makes it all the more touching, as when Bess talks out loud in two-way conversations with God, speaking both voices–making God a stern adult and herself a trusting child.

6. SCHINDLER’S LIST

The French author Flaubert once wrote that he disliked Uncle Tom’s Cabin because the author was constantly preaching against slavery. “Does one have to make observations about slavery?” he asked. “Depict it; that’s enough.” And then he added, “An author in his book must be like God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere.” That would describe Spielberg, the author of this film. He depicts the evil of the Holocaust, and he tells an incredible story of how it was robbed of some of its intended victims. He does so without the tricks of his trade, the directorial and dramatic contrivances that would inspire the usual melodramatic payoffs. Spielberg is not visible in this film. But his restraint and passion are present in every shot.

5. THREE COLORS TRILOGY: BLUE, WHITE AND RED

Think about these things, reader. Don’t sigh and turn the page. Think that I have written them and you have read them, and the odds against either of us ever having existed are greater by far than one to all of the atoms in creation. “Red” is the conclusion of Kieslowski’s masterful trilogy, after “Blue” and “White,” named for the colors in the French flag. He says he will retire now, at 53, and make no more films. At the end of “Red,” the major characters from all three films meet – through a coincidence, naturally. This is the kind of film that makes you feel intensely alive while you’re watching it, and sends you out into the streets afterwards eager to talk deeply and urgently, to the person you are with. Whoever that happens to be.

4. FARGO

On the way to the violent and unexpected climax, Marge has a drink in her hotel buffet with an old high school chum who obviously still lusts after her, even though she’s married and pregnant. He explains, in a statement filled with the wistfulness of the potentially down-sized, “I’m working for Honeywell. If you’re an engineer, you could do a lot worse.” Frances McDormand should have a lock on an Academy Award nomination with this performance, which is true in every individual moment, and yet slyly, quietly, over the top in its cumulative effect. The screenplay is by Ethan and Joel Coen (Joel directed, Ethan produced), and although I have no doubt that events something like this really did take place in Minnesota in 1987, they have elevated reality into a human comedy – into the kind of movie that makes us hug ourselves with the way it pulls off one improbable scene after another. Films like “Fargo” are why I love the movies.

3. GOODFELLAS

What finally got to me after seeing this film – what makes it a great film – is that I understood Henry Hill’s feelings. Just as his wife Karen grew so completely absorbed by the Mafia inner life that its values became her own, so did the film weave a seductive spell. It is almost possible to think, sometimes, of the characters as really being good fellows. Their camaraderie is so strong, their loyalty so unquestioned. But the laughter is strained and forced at times, and sometimes it’s an effort to enjoy the party, and eventually, the whole mythology comes crashing down, and then the guilt – the real guilt, the guilt a Catholic like Scorsese understands intimately – is not that they did sinful things, but that they want to do them again.

2. PULP FICTION

If the situations are inventive and original, so is the dialogue. A lot of movies these days use flat, functional speech: The characters say only enough to advance the plot. But the people in “Pulp Fiction” are in love with words for their own sake. The dialogue by Tarantino and Avary is off the wall sometimes, but that’s the fun. It also means that the characters don’t all sound the same: Travolta is laconic, Jackson is exact, Plummer and Roth are dopey lovey-doveys, Keitel uses the shorthand of the busy professional, Thurman learned how to be a moll by studying soap operas. It is part of the folklore that Tarantino used to work as a clerk in a video store, and the inspiration for “Pulp Fiction” is old movies, not real life. The movie is like an excursion through the lurid images that lie wound up and trapped inside all those boxes on the Blockbuster shelves. Tarantino once described the old pulp mags as cheap, disposable entertainment that you could take to work with you, and roll up and stick in your back pocket. Yeah, and not be able to wait until lunch, so you could start reading them again.

1. HOOP DREAMS

It is about the ebb and flow of life over several years, as the careers of the two boys go through changes so amazing that, if this were fiction, we would say it was unbelievable. The filmmakers (Steve James, Frederick Marx and Peter Gilbert) shot miles of film, 250 hours in all, and that means they were there for several of the dramatic turning-points in the lives of the two young men. For both, there are reversals of fortune – life seems bleak, and then is redeemed by hope and sometimes even triumph. I was caught up in their destinies as I rarely am in a fiction thriller, because real life can be a cliff-hanger, too. Many filmgoers are reluctant to see documentaries, for reasons I’ve never understood; the good ones are frequently more absorbing and entertaining than fiction. “Hoop Dreams,” however, is not only a documentary. It is also poetry and prose, muckraking and expose, journalism and polemic. It is one of the great moviegoing experiences of my lifetime.