The following article was originally published on June 15th by Greg Carpenter at Sequart.org.

The set was simple—just two men sitting in the cushioned seats of an empty movie theater. One of them was thin, with a long, angular face and a receding hairline. The other was heavy, with a round face and Clark Kent glasses. Maybe it was because the show was on PBS, but when I first saw them as a kid, I thought they looked like a grown-up version of Bert and Ernie. The only difference was that these guys were talking about the movies.

The show was called Sneak Previews, and “Bert and Ernie” were actually two rival film critics from Chicago. “Bert” was Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune and “Ernie” was Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times. I don’t remember how old I was when I first saw them—too young to understand everything they were talking about and certainly too young to see all the movies they were reviewing—but something about them captured my attention.

Growing up in rural Arkansas, I had never heard two adults talk this passionately about something most people regarded as “trivial” like the movies. Siskel and Ebert didn’t pander to the audience; they just talked. Perhaps you remember those times when, as a kid, you managed to slip unnoticed into a room where the “big people” were talking. That’s what the show felt like to me. It was educational in the best sense of the word. I wanted to know what they knew, wanted to understand what they understood, and the burden was on me to elevate my game so I could catch up.

I spent the next several years trying to do just that as a dedicated Siskel & Ebert viewer. When they left “Sneak Previews” to launch their own syndicated show, I followed. They didn’t just review movies; they talked about important issues, campaigning against the colorizing of black and white films and strongly advocating for an adults only rating (what became “NC-17”) to replace the tainted “X.” But for me, the most eye-opening lesson came when they exposed the problems of transferring widescreen films to the nearly square dimensions of an old-style television set. From that point on, I became a zealot for letterboxing, and eventually, the rest of the culture caught up with Siskel & Ebert. (Now if we could only stop stretching old TV images onto widescreen televisions … )

When I entered college, I began reading Roger Ebert’s writing for the first time. Siskel didn’t publish collections of his reviews, but in those pre-Internet days, Ebert published an annual book that included all the past year’s movies as well as important reviews from his archives. I eventually bought three of these books, devouring each one so many times that some of the more interesting of the older reviews took on legendary status. To this day, I can’t think of “2010: The Year We Make Contact” without first thinking of the way Ebert began his review, quoting e e cummings: “I’d rather learn from one bird how to sing than teach ten thousand stars how not to dance.” I didn’t exactly know what that meant, but it sure sounded nuanced.

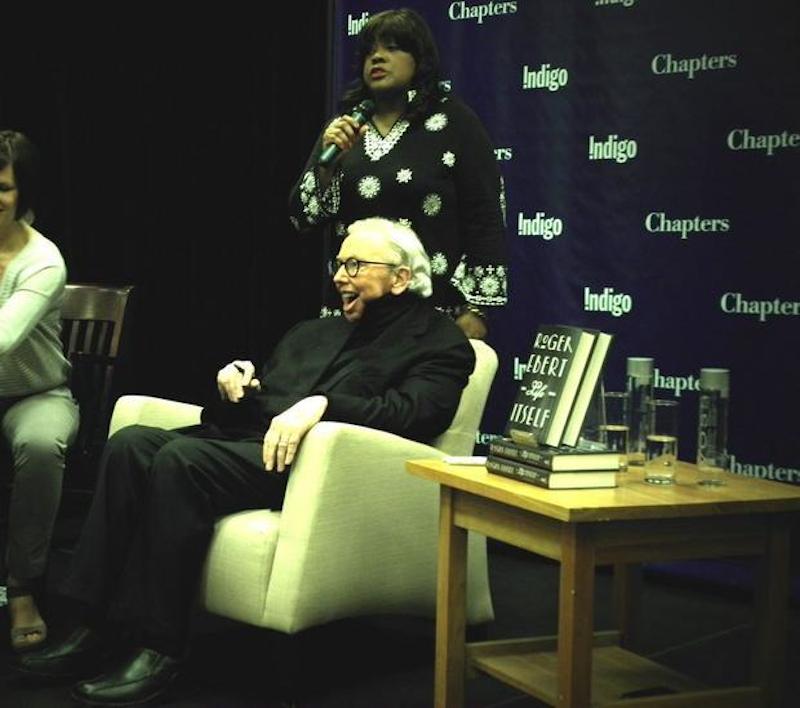

Ah, but here I am, halfway through this column, and I still haven’t explained where this is going. In other words, I’ve buried the lede. As a longtime journalist, Ebert would’ve probably hated that. But the truth is, I just read Ebert’s 2011 memoir, Life Itself, and to be honest, I needed to talk to someone about it.

Sometimes we put off reading things for the strangest reasons. I’m not talking about the times when you say, “I oughtta read War and Peace this year,” but then you don’t. That’s really not all that strange. Your brain and ego may want to dive into thousands of pages of 19th century Russian literary profundity, but your body knows better.

But given how important Roger Ebert has been to me, it is strange that I didn’t leap onto his memoir as soon as it came out. To be honest, I think I was afraid of it. For those who don’t know, the last years of his life were trying times, physically. He fought cancer and suffered through three failed surgeries. When all was done, he had lost his jaw, and with it, his ability to speak, eat, and drink. He was also largely immobilized. When I heard he was writing a memoir, I envisioned a long, detailed account of his medical experiences, and that wasn’t how I wanted to remember him.

I should’ve known better. Just as I had learned as a child from Siskel and Ebert that there was a world out there where grown ups really cared about things like movies, I’ve found that even as an adult, I still have a lot to learn from Roger Ebert. His memoir, Life Itself, is not only one of the best books I’ve read in years, it’s also deeply inspiring. He doesn’t devote endless chapters to surgery and rehab—he devotes them to … well, to life itself. The book presents a portrait of a man who not only knew how to relish a good movie, but who knew how to relish the world around him, highlighting the things and the people that filled him with love and imagination. Even after his death, Roger Ebert is still teaching me.

I’ve long believed that Ebert was underrated as a writer, but this book really proves it. Ebert could’ve been a novelist or a playwright, a political essayist or a sportswriter. He just happened to be a movie critic.

Like any good journalist, Ebert soaked up everything around him—people, cars, houses, clothes, food, hotels. His memoir has a vague sense of chronological progression, but all the chapters are thematic, and at their best, they stand as masterful short essays on all sorts of subjects, including his hometown of Urbana—“the center of the universe” as he calls it—his father, his mother, and the University of Illinois.

He writes with simple clarity, honesty, and a newspaperman’s flair for including just enough memorable details to hold the piece together. Two of the best chapters appear back-to-back, early in the book. By all rights, neither of these chapters should be any good. The first is a rhapsody on the wonders of the Steak and Shake restaurant chain. The subject is absurd and trivial, but Ebert manages to describe the Steak and Shake in such rose-hued, romantic terms that by the time he finishes his argument, I felt convinced that the Steak and Shake was one of the signal achievements of humanity in the 20th century.

But if the Steak and Shake seems too absurd and offbeat for an essay, the subject of the next chapter—dogs—has the opposite problem. It’s hopelessly cliché. How can anyone these days write something meaningful about his love of dogs? Well, Ebert does it. He takes a global approach at first, writing universally about dogs with enough charm, insight, and enthusiasm to win over the most skeptical reader. Then he turns to the specific, writing about a single dog from his childhood. Even though the story ends with pathos as all dog stories do, it’s pathos of a different sort—a sadness that speaks more towards his relationship with his parents, his career, and his physical ailments than it does the fate of this one, particular dog.

Both of these chapters are brilliant exhibitions of how to write effectively about subjects that would stymie the best of writers. Of course it helps if you really know how to engage with your surroundings. Throughout the book, Ebert comes across as someone who genuinely loved the things and people he encountered. He loved his hometown, his college, his newspaper, his friends, his lovers, and his travels. Like most great writers, he doesn’t explain so much as he inspires.

The middle section focuses on his career—both as a newspaperman in Chicago, hanging out after hours with the likes of Mike Royko and Studs Terkel, and as a film critic, interviewing people like Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, Robert Mitchum, Lee Marvin, and John Wayne.

In fact, so much of the book focuses on others that it almost becomes a weakness—as if Ebert were somehow dodging his own character and letting others do all the heavy lifting. But when he nears the final chapters, he begins to open up in very personal ways. His chapter on his various romances, for example, isn’t a kiss and tell, but rather, ultimately, an exploration of the way in which he struggled to separate himself, as an adult, from the influence of his mother and his Catholic upbringing.

He then describes the cancer and the failed surgeries, with the final chapters discussing illness, death, and religion in very candid ways without ever becoming morbid or maudlin. In fact, through it all, Ebert’s narrative voice remains cheerful, optimistic, and uncannily reasonable to the end.

Life Itself is a truly remarkable book—beautifully and thoughtfully written, and reading it has reawakened my passion for the movies—something that has often become dulled over the past few years. In fact, next week I plan to look more closely at Ebert’s place as a critic in the midst of the Golden Age of American Film Criticism.

Click here to read part 2 of Greg Carpenter’s analysis of the Golden Age of American Film Criticism. Purchase the book Life Itself at the following online retailers: