Claude Chabrol, who died Sunday, Sept. 12 at 80, was a founder of the New Wave and a giant of French cinema. This interview, which took place during the 1970 New York Film Festival, shows him at midpoint in his life, just as he had emerged from a period of neglect and was making some of his best films.

By Roger Ebert

NEW YORK — Claude Chabrol’s “This Man Must Die” is advertised as a thriller, but I found it more of a macabre study of human behavior. There’s no doubt as to the villain’s identity, and little doubt that he will die (although how he dies is left deliciously ambiguous).

Unlike previous masters of thrillers like Hitchcock, Chabrol goes for mood and tone more than for plot. You get the notion that his killings and revenges are choreographed for a terribly observant camera and an ear that hears the slightest change in human speech.

For this reason, particularly, it’s necessary to put up a squawk and insisted on the film’s original subtitled version; without the rhythm of the sound track, the movie simply doesn’t work. New Yorkers saw the subtitles, of course, but Allied Artists apparently decided to let the rest of the country see a wretched botch of a dubbing job.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the dubbed version flopped; “Z” ran for months in its exquisite subtitled version, but flopped in the neighborhoods because a lousy dubbed version was substituted.

Let’s face it. Movies by director like Chabrol or Costa-Gavras are intended for the more literate section of the movie audience. You can dub a spaghetti Western and nobody cares, but mess with Chabrol and you’re eliminating the very quality audiences respond to in his work.

In any event, we’re seeing the good version here, and it is one of the best Chabrol films since he began his new career as a student of murder. With Godard veering ever more erratically into left field, and Truffaut exhibiting an alarming tendency to get cute, it’s actually beginning to appear that Chabrol will become the front-running French director of the 1970s – commercially, and maybe even artistically.

Yet as recently as 1967, in his “Interviews with Film Directors,” Andrew Sarris was actually able to write about Chabrol in the past tense: “He quickly became one of the forgotten figures of the nouvelle vague . . . Chabrol found himself so demode by the mid-1960s that he was forced to accept commissioned projects to keep his hand in.”

But just then, when his career as a serious director seemed most in doubt, Chabrol arrived at the 1968 New York Film Festival with “Les Biches.” It was an artful combination of lesbianism and very Chabrolian irony, with a nice bit of murder at the end, which forced you to re-think all the characters. And Chabrol, the first of the New Wave directors to be hailed and the first to be dismissed, was very clearly back in business again.

Les Biches

“Les Biches” was the first film Chabrol made with Andre Genovese, a young Parisian who is, Chabrol says, the only producer he has ever been able to work happily with. They followed it with “La Femme Infidele” (1969), Chabrol’s greatest critical success since “Les Cousins” a decade earlier. Then came “This Man Must Die,” “Le Boucher,” one of the hits of this year’s New York Film Festival, and “Le Rupture,” still unseen in the United States. (“We’re certainly going to have to change that title for the American release,” Chabrol notes cheerfully.)

Taken together, this group of films seems to announce that, at 40, Chabrol is finally realizing the great promise of his early career, There have been 18 Chabrol features so far, and they reflect a distinctly erratic chapter in the history of the New Wave. Chabrol was there at the very beginning, first as a critic for Cahiers du Cinema and then as the director of perhaps the first New Wave film. His “Le Beau Serge” (1958) preceded Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” by a few months, and when Godard’s “Breathless” appeared the original triumvirate of New Wave directors was established. It still rules.

Chabrol’s sensationally successful “Les Cousins” followed, also in 1958, and the next year he made “A Double Tour” and “Les Bonnes Femmes.”

Although he was by then routinely linked with Truffaut and Godard, his style and taste in material didn’t resemble theirs (nor did they resemble each other, of course, although they made a convenient grouping because of their common disregard for the existing writer-dominated French cinema.)

Chabrol’s 1962 “Landru,” from a screenplay by Francoise Sagan about a World War I mass murderer, can be seen in hindsight as characteristically Chabrolian but having little connection with the concerns of other New Wave directors. It was coolly professional and exhibited the fascination with murder that has been his subject in all the recent films produced by Genovese.

Le Boucher

“Landru” was a commercial and critical success, but “Ophelia” the same year was a failure, beginning a period of involuntary idleness for Chabrol. He married the actress Stephane Audran in 1962 (she was Jean-Louis Trintignant’s former wife and had starred in “Les Cousins”). And then he announced a number of projects, but nothing came of them. In 1964 he directed the first of three comedy thrillers he considers potboilers.

All three were frankly jobs done for money, and if some auteur critics defended them, not many others found them worthy of Chabrol. A 1967 “comeback” project for Universal’s European production division, “The Champagne Murders,” starred Anthony Perkins and was praised in France. But the mutilated U.S. version was a disaster.

One night recently, Chabrol sipped a Scotch and soda in the Greenwich Village apartment of a friend, and talked about it.

“How do you become a director? First, you must start. Second, you must find a producer who is a human being. Andre Genovese is a human being. I can say of all my previous producers that I hated them and they hated me. Just before I met Andre, things were at their blackest. I was doing ‘The Champagne Murders,’ and the producer, so called, was a young man named Jay Kanter who was in charge of Universal’s operation over there.

“He was a good agent, they told me. Why not? But as a producer he was a joke. After I finished the film, they brought in an editor who was described as a ‘doctor.’ He was supposed to make a film out of my film. So what did he do? He made a hodgepodge. For the English version, he cut out 20 -minutes, and inevitably they were the exact 20 minutes for which I made the film.”

Chabrol spread his hands in a gesture of futility. “Editors have an uncanny ability to find what you feel is most important, and cut it out,” he said. “I could have made a stink, but I wasn’t in a very strong position just then. At least they let me have the final cut for the French version. Perhaps I’m not the purist I ought to be. When we were all writing for Cahiers, we looked at Hollywood films that everyone thought were commercial, and we discovered art and morality in them. Fifteen years later, with these recent films of mine, perhaps I’m taking art and morality and making them commercial . . .”

In a sense he’s correct, although “commercial” is a word too negatively charged to describe the exquisite subtlety of “Le Boucher” or “This Man Must Die” (even if they are advertised as thrillers).

Perhaps professionalism is the quality that ought to be substituted; the early Cahiers critics appreciated that quality to such a degree that they actually prized directors whom accepted routine assignments and turned them out competently. Even today, when the budget is not exactly critical, Chabrol makes a point of telling you that John Ford shunned covering shots, and that every shot Chabrol takes is in the film.

Because Genovese respects this, Chabrol says, he gives Chabrol a free hand in making his films, and that, you see, is why the last three years have been so productive for Chabrol.

“Most of the French producers,” Chabrol explained, “are like Zanuck. No, not like Zanuck. Like a little Zanuck. I have a certain regard for Zanuck himself. You know I used to work for him. That’s right! I was the Paris publicity man for 20th Century-Fox in 1955.”

Chabrol sipped his Scotch very seriously, for comic timing, and then allowed himself to grin. “When I quit,” he said, “you’ll never guess who got my job. I gave it to Jean-Luc Godard. Of course he was even worse as a publicity man than I was.

“He always made sure to have the lavatory key. He would come into the office and look busy for an hour, and then say he was sick. Then he would lock himself in the lavatory and read scripts. I know the feeling because I like to read all the time myself, when I’m not watching movies. During the war I was sent out into the country — I must have been about 10 at the time — and I read detective novels all day.

Ten Day’s Wonder

“It was at that time I first read ‘Ten Days Wonder,’ by Ellery Queen, which will be my next film. In writing the script, I worked from the very same copy of Ellery Queen that I read 30 years ago.

“When I wasn’t reading I was going to the movies. I saw ‘Snow ‘White’ at least 10 times between 1937 and 1940 and I think it influenced my work, a little. It was a good horror film. The death of the witch was the best thing Disney ever did. Of course, murder always heightens the interest in a film. Even a banal situation takes on importance when there’s a murder involved.

“I suppose that’s why I choose to work with murder so often. That’s the area of human activity where the choices are most crucial and have the greatest consequences. On the other hand, I’m not at all interested in who-done-its. If you conceal a character’s guilt, you imply that his guilt is the most important thing about him. I want the audience to know who the murderer is, so that we can consider his personality.”

Chabrol said he is rather happy right now about the way his career is going.

“With the films since ‘Les Biches,’ I think I’m on the right track. Not that I was ever on the wrong track, but I believe that period of idleness helped me think things over. You might consider a concert pianist, suddenly unable to give concerts. So he sits at home and practices for two or three years, until somebody hires him again. And then they don’t think about the two years, they think about how well he plays . . .

“Certainly I’m happy right now making these films about murder. My interest isn’t in solving puzzles, but in studying human behavior. Nothing else interests me so much. I’m not a chansonnier, a man obsessed with the events of the day. I am a Communist, certainly, but that doesn’t mean I have to make films about the wheat harvest. I think Godard’s political films have been messy. Right now, Jean-Luc seems to be going through a bachelor’s crisis: Should I marry politics or remain free?”

Chabrol leaned forward to share a confidence.

“I’ll tell you a Party secret,” he said. “Spiro Agnew is a double agent. Of course, he doesn’t know it, but that’s the best kind of agent there is — because he can never blow his own cover!”

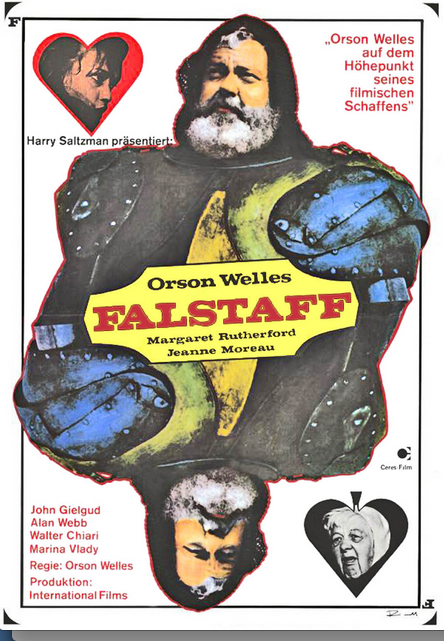

His face opened into a beatific smile. He finished his Scotch. He sighed. “Now we go back to France to make a film about murder again,” he said. “In this one, I kill everyone, but it’s no big deal. They’re living at the beginning and dead at the end. In between, there’s a story about a man who breaks the Ten Commandments, one by one. Catherine Deneuve will star, and of course Orson Welles will play God.”

I have many Chabrol reviews online. Use Search on my home page. Here is my Great Movies Collection review of Le Boucher.

From the Telegraph, the best Chabrol obituary..

Chabrol’s 50th and final film: “Inspector Bellamy” (2009)

☑ All of my TwitterPages are linked under the category Pages in the right margin of this page.

var a2a_config = a2a_config || {};

a2a_config.linkname = “Roger Ebert’s Journal”;

a2a_config.linkurl = “http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/”;

a2a_config.num_services = 8;

April 9, 2013