It takes an election cycle as wretched as 2016’s to make the scandals and attack ads playing in the margins of “The War Room” seem quaint.

Co-directed by D.A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus, and focusing on Bill Clinton’s campaign communications director George Stephanopoulos and his campaign manager James Carville, this chronicle of the 1992 Presidential race gave audiences a rare glimpse of how the political sausage is made. How civil the uncivil business of stirring up trouble for your opponent once was is startling. It’s strangely melancholy to see that, in a wild election year that saw the Gennifer Flowers scandal and the independent candidacy of Texas billionaire Ross Perot, the campaign narrative was being written by men and women in offices and hotel rooms, making phone calls on land lines and huddling over cans of Diet Coke.

The film builds a motif of politics as canny stage management. It’s about carefully pulling the side table over the grease stain on the carpet so the guests won’t see it, or dropping, with passive-aggressive cool, a most unfortunate story that someone told you about the neighbors. Pennebaker and Hegedus eschew traditional cutting in of talking heads interviews to move the camera unobtrusively but intelligently within the various spaces, as if the movie itself is restlessly curious, always looking for the next revealing gesture or line. It’s that itch to know more that holds the viewer’s attention, too; we often find ourselves trying to decode the meaning of a silent glance, or intuit the other half of a phone conversation where only the person in the room is heard.

“The War Room” is a picture of the American Left wandering out of the wilderness of the 1980s and gaining national power by shedding the radical unpredictability of the sixties for the burger chain with a jukebox rebellion of Bill Clinton’s saxophone. And yet, perversely, you still get a sense of real people struggling to fill roles they hope to win, for the good of the country. Carville gives a St. Crispin’s Day style speech the night before the election and his tears are real. There is no playing to the camera when he tells the assembled room how proud he is of what they built together. But there are intimations of what would come in a scene of Carville warning that Roger Ailes—then an advisor to Bill Clinton’s opponent George H.W. Bush, and still four years away from founding Fox News Channel—will be the architect (along with Bush strategist Karl Rove) of most of the rumors and smears that voters will hear about the Clintons during the next eight years. This sense of dread is only somewhat mitigated by the movie’s belief in the transformative power of government and a shared future, underlined in scenes of Carville talking with Bush campaign staffer Mary Matalin—who he would marry the following year—about their days on the trail, without giving each other any salient info to take back to their bosses.

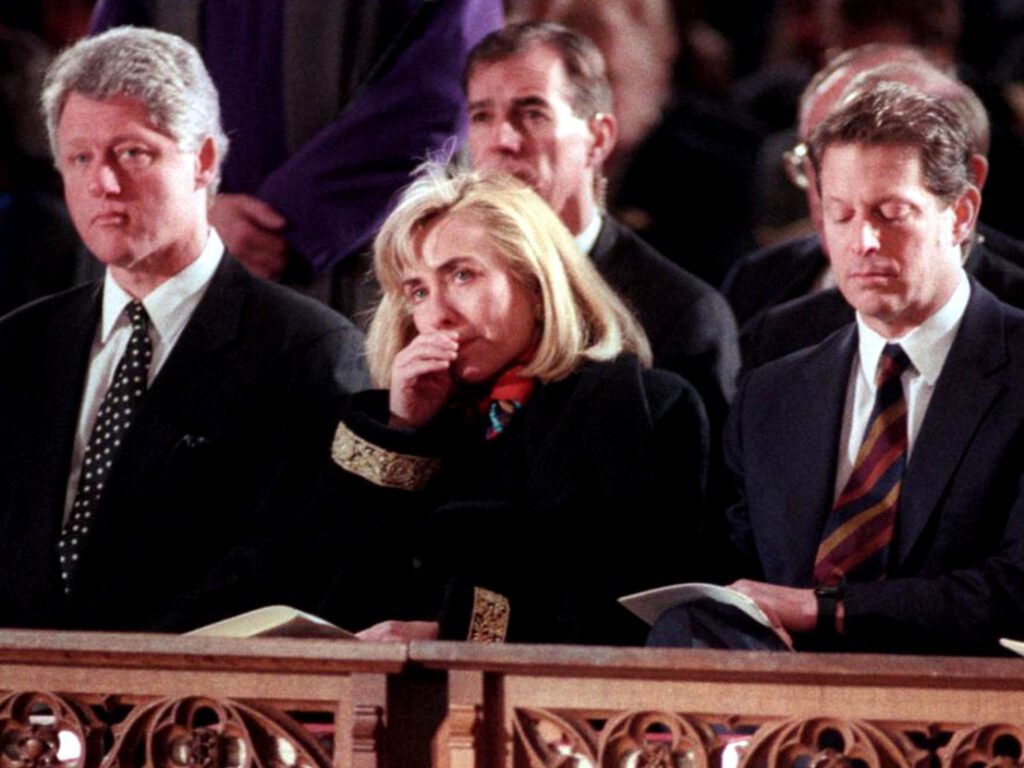

It’s impossible to watch “The War Room” today without looking for Hillary Clinton in the frame. She’s barely in it. We first see the back of her head, hair spilling from a black headband as she introduces herself as “Hillary Rodham Clinton” to a deli counter worker. The next time we see her in a scene, she’s visible on a TV in the room at the Democratic National Convention. Some viewers might notice change that this film focused on men doesn’t comment on: she now sports the sleek bob of the “politician’s wife.” That change in appearance was a defensive move. Nineteen ninety-two marked her first trial as a woman in the national stage who could never do anything right. She caught grief for her headband and “unprofessional” hair. It was not the first or the last time that the future First Lady, senator, Secretary of State and presidential nominee would catch grief for her looks and appearance.

It’s happening again right now as she campaigns to become the first woman president of the United States. “The War Room” is an entertaining if sometimes cynical film, a movie about process; it took an opponent as vile as Donald Trump to make watching it a sad experience.

Clinton’s opponent is not just disrespectful of her, he’s unqualified to face her. It’s impossible for male friends of women, no matter how empathetic, to understand how demoralizing that is. They don’t know what it’s like to swim in misogynist bile for months and have it seep through your skin like some corrosive chemical, until you’re no more than bone and ash, then keep going, because you know that if you talk about how tired you are—how much this experience hurts on levels you were not expecting—you will be dismissed as weak. As a complainer. As somebody not cut out to deal with the real world. And throughout, to be denied the outlet of anger that Trump’s supporters celebrate him for using.

It’s also hard not to wince at the film’s opening minutes in which Gennifer Flowers confesses to an affair with Bill Clinton, envisioning smirking tabloid headlines 24 years later that seek to punish Hillary Clinton for her husband’s behavior. Trumpism grew from the seed bed of every lie, conspiracy, and smear that Ailes, Rove and like-minded operatives and pundits could dream up; three decades of hating Hillary Clinton have reached a hideous crescendo, with the Republican nominee for President fending off accusations that he tried to force himself on a People Magazine reporter by saying he would never grope such an unattractive woman, and letting an audience at a rally know that he walked behind Hillary Clinton at the second debate and was not impressed. A stinging rebuke to every woman watching that no matter your smarts, your drive, your desire to do something big, you will be judged on whether or not you give your sharpest critics an erection.

Although the movie paints a gentler picture of presidential campaigning than we are used to seeing today, there is still an overwhelming maleness to “The War Room” that can be suffocating, even if you understand that it’s painting an accurate picture of the gender politics of politics circa 1992. Matalin and Hillary Clinton’s cameos notwithstanding, this is a very male movie about a business that was (and still is) driven by men. The narrative is largely about the stories men tell about themselves and each other. It swerves around big picture narratives to zero in on the guys whose unspoken job it is to save Bill Clinton from himself. As entertaining as it is to watch Stephanopoulos and Carville banter and plot, the movie might have been richer had it paused to focus on the women working diligently in the background of almost every scene. There might have been another Hillary Clinton back there for all we know, cold-calling registered voters between sips of Diet Coke.