Professional campaign managers have had a bad image as long as they’ve had an image at all, which is roughly since the publication of Joe McGinniss’ The Selling of the President: 1964. The occupation did not gain any luster last November when Ed Rollins shot himself in the foot with his tales of bribing New Jersey preachers. The typical campaign manager is seen as a Machiavellian spin doctor, and that’s on a good day.

Perhaps the documentary “The War Room” will bring a deeper dimension to the profession’s image. At the very least, it may dispel the notion that campaign managers pervert the course of democracy with behind-the-scenes omniscience; the surprise in the film is that they’re often as confused as their candidates sometimes seem to be.

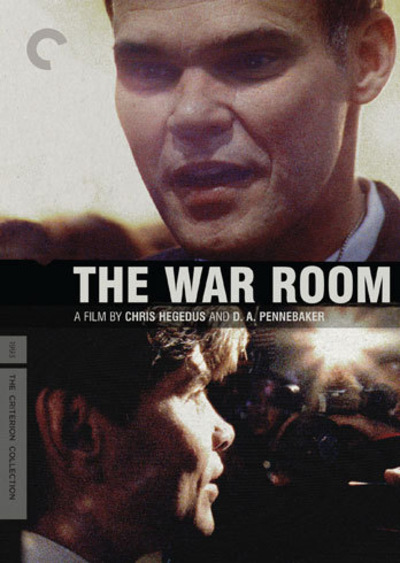

Filmed by the veteran documentarian D.A. Pennebaker and his wife, Chris Hegedus, the movie follows key members of Bill Clinton’s campaign team from the snows of New Hampshire in January, 1992, to the victory celebration in Little Rock in November of that year. The movie’s stars are James (“The Ragin’ Cajun”) Carville, the impish chief strategist for the Clinton campaign, and George Stephanopoulos, the young, polished former Rhodes scholar who was the campaign’s media director.

The two are seen working together in an inside-outside combination. Stephanopoulos, often in a suit and tie, handsome in a Kennedyesque way, is the relaxed, usually calm press spokesman.

Carville, a tense and driven man who seems to shop for his clothes at the LSU sports store, works behind the scenes, often in the campaign’s “war room” in a converted newspaper office in Little Rock.

Strategists would no doubt like to see themselves like modern Napoleons, moving pawns on the maps of continents. More often, this film shows, they get involved in screwy debates about the color, typography and size of their campaign posters. Their dedication to “the Candidate” is easily matched by the intensity with which they despise their opponents – and especially their opponents’ troops, suspected in New Hampshire of tearing down Clinton signs (something, of course, Carville’s volunteers would never, ever do . . . except, of course, in retaliation).

Most of the opening footage in the film was gathered by Pennebaker and Hegedus from TV and documentary crews who were on the scene in the early primaries. Their own footage begins at about the time of the Democratic Convention, where Clinton was nominated, and follows Carville and Stephanopoulos down the increasingly rocky road to the election victory. They allow the cameras access to surprisingly unguarded moments, as when they brief their squad of spin doctors after one of the Clinton-Bush debates (“Just keep on repeating that Bush was on the defensive all night”), and when the press reports on Clinton’s draft history, Carville complains, “Every time somebody even farts the word draft, it makes the paper.” Given the various scandals and would-be scandals that pursued the Clinton campaign, it seems almost incredible that he survived, and won. There is footage from grim early days in New England, right after the supermarket tabloids broke the first charges of Clinton’s adultery, and footage months later, two days before the election, of Stephanopoulos calmly talking on the phone with a man who had still more hearsay he wanted to ventilate.

What you realize, watching Carville and Stephanopoulos move between grand strategy and damage control, is that they are good at their jobs, and probably as honest as was possible under the circumstances. Certainly their decision to allow access by documentarians shows a willingness to be seen, warts and all.

Carville is moving in a speech to his troops on the eve of the election. Exhausted, strung out, on the brink of tears, he tells them that politics has been his life, and that it is a life worth living.

Of course, during the course of the campaign, his own personal life changed dramatically when he became engaged to Mary Matalin, the strategist for the Bush campaign. How did they meet, how did they start dating, and what did they talk about? Now that would have made a movie.