The heroine of Mamoru Oshii’s landmark anime film “Ghost in the Shell” is Major, aka Motoko Kusanagi, an artificial life form grappling with questions about her soul, her humanity and the body in which she resides. She is a cybernetic warrior employed by tactical force unit Section 9, cracking down on crimes within “the net.” But she can’t crack open the reasoning behind her own existence.

Her journey illuminates a skill that transgender people must learn in order to survive: reconciling the body and the mind.

A recent scientific study theorized that gender dysphoria sends signals to the brain that tell the body it is injured. That means that you are living as a wounded creature, except the wounds can’t be patched up; you just have to get used to carrying them.

There are very few movies about the actual experience I’ve described. There is a transgender cinema, but outside of documentaries it has had no real bearing on the reality of being trans. There are a number of reasons for this, including a longstanding history of transphobia and a dearth of transgender producers, directors and writers in the film industry. But the upshot is that, until quite recently, the only place to see a version of the trans experience was in movies that are not officially about being trans, but which deal with crises of identity and the displacement of bodies.

These tend to be genre films whose images are not exact matches for the trans experience but still reveal something authentic. The parallels tend to be subtextual, and a lot of the time they were not intended to be read that way. But the better-executed stories still get inside the skins of characters who are not content with the bodies they were born into.

Some of the best examples are science-fiction films about characters who happen to be alien or born of artificial intelligence. The original “Ghost in the Shell” is one of the best.

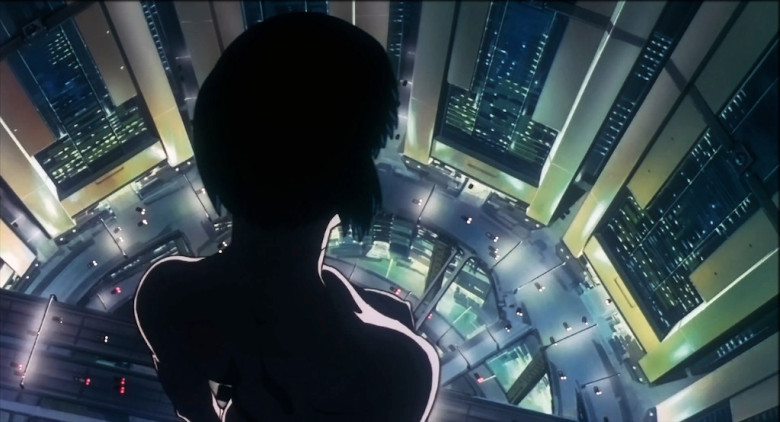

“Ghost in the Shell” starts with a shot of the Major crouching atop a high-rise building, talking shop with her superior officers. She says there’s a lot of static within her brain and it must be that time of the month again. A few seconds later, we get a full reveal of her body. It is female in form but essentially sexless. She lacks the genitals she would need for reproduction, and her half-formed breast tissue likewise lacks biological function.

The Major was devised to be a tool of Section 9, but this hasn’t stopped her from considering the state of other women and their own biological nature. She is held at bay by the limitations of her own body, and Oshii conveys this beautifully through frequent images of solitude where the film quietly observes the Major as she considers her identity and her own skin. These images capture the way transgender people obsess over the nature of the human form. They are constantly aware of the body, of the inability to rest within skin that has been molded into something that was never asked. Biology never considered their consent.

The Major is framed with an almost god-like reverence. She is often filmed in low-angle shots that show her as a towering figure. But the downcast expressions she carries on her face disrupt the image worship and imbue the narrative with a tragic flavor. There is a schism between the way the camera treats Motoko and how empty she feels. This is portrayed beautifully even within the title of the film: “Ghost in the Shell” is a loaded phrase that evokes a spirit dwelling in a hollow state.

This idea carries over into the relentless philosophizing of Major Motoko and her partner Batou. In the movie’s dystopian version of Tokyo (2029, to be exact), the human body can be “enhanced” through cybernetic implants and machinery. This bothers Motoko even though she’s an artificial creation herself. During one sequence, Motoko and Batou discuss the nature of humanity on the dock of a boat beneath a breathtaking midnight sky. Motoko questions whether the efficiency of machines within everyday humanity has caused a rupture in the soul. Batou, who has enhanced eyes, asks the Major what defines humanity to which she replies it is the individuality of voices, faces and memories. This is something that Major has obsessed over, too.

It is within the Major’s pre-internet, A.I. anxiety that this story becomes distinct to Japan. The Major’s technological worries speak to a more current nightmare state, one of streamlined technological advances that mirror a society that is becoming absorbed into the internet. At the time of the film’s release, Japan was on the frontlines of brand new tech that would make that idea a reality.

Motoko’s feeling of displacement extends to Tokyo as well. We see this dramatized in a two-minute sequence of scenery show from her point of view. The images take her personal concerns and make them national. Oshii’s 2029 Tokyo is a land in decay that’s being broken down in favor of a newer, sleeker version. On the edges of Tokyo, poverty seems to eat at buildings like a disease, but their weathered qualities make them stunning. In other areas, there’s a clear sense of the future as a perfect, machine-like object with glistening walls and shifting elevators. This plays into Motoko’s concern that human error is being lost in the wake of the perfection of machinery.

The sequence also speaks to her personal crisis: a fear that identity is being swallowed up by a constructed object. Its defining image is also the most emblematic one in the entire film: a mannequin.

Mannequins exist only to display something, usually an article of clothing, but in this longer scene where Motoko traverses the city it tells us a lot about how she feels. Motoko is a half-formed thing. She looks like a human being but doesn’t have the essence of one. The Mannequin is her relatable figure.

The Major’s interest in the mannequin also ties into her function as a weapon. Whether she learns to exist on her own terms as a constructed human being or reconciles her innate and artificial aspects, how can she also exist as an object of destruction? Motoko does not know the answers to these questions. The film doesn’t resolve them. It only asks us to experience the disparity within her, and empathize with her predicament.

Motoko’s struggles come to a head later in the film, when she meets the perceived villain known as “The Puppetmaster,” whose real name is Project 2501—a virus that became sentient on the viral network now seeks a body. Motoko empathizes with 2501 as a fellow A.I. that is also struggling to reconcile her mind and body. When 2501 is first brought in by Section 9, she is introduced as a being of clipped femininity: her shell is fractured from the waist down, mirroring Motoko’s featureless genitalia. Despite existing within a female body, 2501 speaks with a masculine voice and is referred to as “he” or “him,” a predicament that will resonate with transgender people.

Her biggest problem is how to reproduce. In a final confrontation with Section 9, which wants to mute her within the network, 2501 tells Motoko: “In you I see myself. As a body sees its reflection in a mirror.” What transpires is a beautiful declaration of love. One figure becomes singular within another. This is another form of reproduction: not through child bearing, but through the evolution of self. Motoko finds her humanity in her willingness to change, and 2501 finds her own femininity within Motoko.

All this is merely alluded to through image, but by keeping these resolutions vague, the filmmaker gives viewers a much wider imaginative space to enter. The years since the film’s initial release have seen many new medical discoveries that can see transgender people evolve into themselves. While the question of transgender childbirth remains unanswered, there is still a sense that, by becoming yourself at last, you too are bringing a new person into the world.

Rupert Sanders’ live-action remake could have attained the same power, but his new feature struggles to adapt the text of the Japanese version. The movie’s interest in identity is barely skin deep. It replicates some of Oshii’s basic instincts as a filmmaker while missing the underlying philosophy that made his style so exciting. The result is a cheap copy that fetishizes Japan while contributing no new ideas. Ironically, the film’s star, Scarlet Johansson, has starred in Major-like roles before to great success in “Lucy” & “Under the Skin,” a film with its own transgender ramifications. Too bad her casting here is at odds with the original movie’s opening statement that “countries and races are not yet obsolete.” Instead, the original text is betrayed through white-washing and when that very subject is brought up in the film it isn’t addressed beyond surface level acknowledgment. What follows is a tone-deaf misreading of the film’s original conflict of soul within body.

Audiences in search of filmmakers with a true vision should look beyond this bastardized text. One point of interest is the filmography of Lily and Lana Wachowski, who cite the original “Ghost in the Shell” as a major influence on their classic “The Matrix.” With cyberpunk imagery and its thoughtfully articulated anxieties about identity and existence in a technological state, it is the only true North American answer to “Ghost in the Shell.” They are currently the only transgender filmmakers making movies at the Hollywood level and they’ve continued to push boundaries of identity in cinema. In particular, their Netflix series “Sens8” has grappled with the problem of subtextual transgender movies by doing away with theory & simply pushing trans bodies to the forefront.

Cinema is evolving, and, even with the slow process of equality, slight fissures in the process of narrative storytelling have been present. There’s a place for subtextual readings, but a more rounded portrait of authentic experiences is the end goal of a Utopian cinema. Oshii’s “Ghost in the Shell” will always strike a chord with those directly affected by bodily displacement. By being brave enough to confront its themes of identity, “Ghost in the Shell” stands tall as one of the very best films ever made about being an alien in your own skin.