When I was about eight or nine years old, my father became my personal “Q,” as we sat in a car outside Southland Mall in Kalamazoo, and he explained a wondrous new gadget that couldn’t possibly be real.

“It tapes things off the TV?,” I asked tentatively, trying to wrap my head around what I was hearing about this “VCR.”

“Yes,” my father replied.

“And you can watch them…anytime you want?”

“Mmm-hmm.”

My own spy-like adventures at that age had involved seeing how long I could stay in the family room past my bedtime, in order to catch glimpses of the “grown-up” programming airing on TV. I knew what this new gizmo meant, and how it would change our viewing habits. And the fact that there was a James Bond movie on that very night made it extra-special.

For a subsequent generation who grew up with VCRs (and DVDs, and streaming) as givens of one’s home viewing, it’s hard to explain what the broadcast versions of the James Bond movies (usually shown on ABC) meant in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Yes, they were cut up and strewn with commercial interruptions. Yes, they were pan-and-scanned, in that pre-letterbox era. But they were there, and in an age of three networks and sometimes-tacky programming, they were an Event, particularly for a nerdy young boy like me. And with the coming of the VCR, I could not only watch them (even if they aired when I was supposed to be sleeping), but could watch them repeatedly, fast-forwarding through the “boring parts” (dialogue, kissing) to the chase scenes, shoot-outs, and gadget-strewn mise-en-scenes that I could run back and forth over and over, like 007 playing with one of Q branch’s weapons.

This was how I discovered “The Spy Who Loved Me,” which celebrates the 40th anniversary of its American release this week, and how I discovered Roger Moore, who quickly became My Bond, in the way that Sean Connery had been for my parents’ generation.

“The only piece of advice I’d offer anyone regarding playing Jimbo,” Roger Moore wrote in his witty remembrance of the series, Bond on Bond: Reflections on 50 Years of James Bond Movies, “is you use what you have in your own personality and be true to yourself, while stealing a bit here and there for added effect.

“Nostalgia is quite handy, too,” he added, “as you’ll find people who are rather unforgiving at the time often rediscover you in later life.”

When Moore died this past May, the nostalgia he recognized kicked into high gear, as a legion of fans who’d loved his portrayal of the character he insisted on referring to as “Jimmy Bond” shared memories on Facebook, Twitter, and fan sites about what his particular personality had brought to the series.

But these acts of mourning and remembrance felt like more than just nostalgia for an older era. One of the pleasures of the long-running Bond series is how each actor’s portrayal allows different facets of the character’s mythology to be emphasized. The constant references this May to the wit, charm, and sense of camp that were Moore’s “added effects” (in contrast to Connery’s crueler blend of humor and action, and subsequent Bonds’ ever harder-edged portrayals) suggested a longing for effervescence in an age of grim ’n’ gritty blockbusters. “Spy” has certainly held up better than the “don’t you dare laugh” self-seriousness of something like Daniel Craig’s “Quantum of Solace.” And much of that should be credited to a man who noted in interviews that one couldn’t be a spy if every bartender in the world knew how to make your martini.

“The Spy Who Loved Me” details Bond’s adventures in teaming up with Soviet agent Anya Amasova (Barbara Bach) against the menacing henchman Jaws (Richard Kiel) and the global domination schemes of super-villain Stromberg (Curt Jurgens), who wants to blow up the world and start anew from his underwater lair. It was Moore’s own favorite among the seven Bond films he made between 1973 and 1985. Despite that he got shingles in the middle of filming, despite an accident while shooting the film’s climax that caused his rear end to catch fire, despite the Egyptian governmental censors hanging about the shoot in Cairo (which meant that some of Moore’s jokes in those sequences had to subsequently be looped in back in London), he claims, in his memoir My Word is My Bond, to have had a thoroughly delightful time on set. Moore praises co-stars Bach and Kiel (who, he says, had such bad vertigo that they had to find a seven-foot stunt double for some fight scenes), expresses awe at the design work of Ken Adam (who built the Pinewood Studios’ “007 stage”— subsequently used for years of blockbuster films—specifically to give them space for the movie’s vast climax in a submarine hanger), and lavishes love on producer Cubby Broccoli (going it alone for the first time as a Bond producer, following a split with partner Harry Salzman).

Above all, he speaks with affection about director Lewis Gilbert, with whom he shared a love of practical jokes, silly puns, and improvisation. Early on, he approached the “Alfie” director and expressed qualms about the script: “The problem was, I thought, that too much emphasis was placed on the extravagant and spectacular— the size of everything … without too much though to the dialogue. I knew the character by now, and knew what he would and wouldn’t say.

“Lewis looked at me. ‘Well, dear,’ he said in his typically vague manner. ‘I’m sure we can make something up and improve it on the day.’”

Moore credits Gilbert with making a lighter film than his previous two efforts (the odd spy/blaxploitation hybrid “Live and Let Die” and the lugubrious “The Man With the Golden Gun”) and “wanting to have fun with it all all and make it slightly ridiculous—a giant with steel teeth, for instance? It suited my style and my persona and I think I really settled into the role with this film.”

“The Spy Who Loves Me” marks the first time Roger Moore appears in the flesh in the pre-credits sequence (he doesn’t appear at all in the pre-credits to “Live and Let Die,” and appears in “The Man with the Golden Gun” as a cardboard cut-out in Scaramanga’s shooting gallery, perhaps a visual confession by the filmmakers of how stiff his character is in that film). The epic sub hijack and ski chase in this sequence—culminating in Bond surviving a leap off a steep mountain cliff by opening a Union Jack parachute—suggests that after an early-to-mid-seventies lull, Broccoli and his team were ready to take the whole enterprise seriously again by not taking things too seriously.

“The Spy Who Loves Me” is a triumph of absurdity, easily the best of the Moore films because it works so hard to make everything a great lark of plasticity and humor. In his wonderful, definitive James Bond Bedside Companion, critic and novelist Raymond Benson graphed out, in witty detail, side-by-side-by-side story comparisons of “Spy,” “You Only Live Twice” and “Moonraker,” the three Bond films directed by Lewis Gilbert, and came to the conclusion that they were all basically telling the same story with only slight variations in names and settings. And if this is the case, what matters is less the horizontal line of narrative motion, and more the vertical line of style, and “The Spy Who Loved Me” has a great deal of fun zigging and zagging across it.

Ian Fleming famously barred film producers from doing a straight adaptation of his original novel, which was written from the perspective of the novel’s heroine, and is much less a traditional espionage narrative than a floating, melancholy tale about memory and sensuality as unstable markers of identity. While the “Spy” film thus completely jettisons the book’s narrative, it captures its odd, distracted tone by constantly shifting the viewer’s attention from story to style.“Spy” is a textbook in visual thinking, asking us to set aside worries about plot or theme in favor of noting the glint off a pair of metal teeth, the wink of a femme fatale as she takes aim at your speeding car, the ripple of a blue-gray wave as a Lotus Esprit shoots underwater. It’s a stylistic space that Roger Moore occupies with tremendous skill, free to finally be the witty, deadpan hero he can be so well, but forced into moments of genuine grace by Bach and genuine terror by Richard Kiel’s wonderfully cartoonish Jaws. Watch that pre-credits sequence again, as the film cuts from the ski-jump work of stunt man Rick Sylvester to Moore’s face as he adjusts his chute: for all his reputation as a Bond funnyman, he doesn’t crack a smile, knowing precisely that a furrowed brow and a slightly raised eyebrow better frame the moment’s tongue-in-cheek spectacle.

Critical perspective on “The Spy Who Loved Me” has shifted several times over the last forty years, depending on the cultural and theoretical fashions of the moment. Initial newspaper and magazine reviews were mostly positive, appreciating “Spy” as an upgrade from the previous “The Man With The Golden Gun”— Roger Ebert gave the film a rave, while Pauline Kael wrote that “The designer, Ken Adam, the director, Lewis Gilbert, and the cinematographer, Claude Renoir, have taken a tawdry, depleted form and made something flawed but funny and elegant out of it.”

Subsequent readings—as the series rejected the outlandishness of “Spy” and “Moonraker” in favor of varying levels of ‘realism’ and ‘grittiness’ between “For Your Eyes Only” and “Casino Royale”—were more mixed. Benson’s “Bedside Companion” (published in 1984), notes its repetitions and flaws while also calling it the best Moore film of the seventies. The cheeky “Kiss Kiss Bang Bang,” published in the Pierce Brosnan era, breaks each Bond film into such categories as “Bonkers plot,” and “Fights, chases, explosions,” and rates each on a scale from 1-10; it gives “Spy” a final tally of 73% and calls it “a slick and vacuous ‘greatest hits’ package’.” In his Bond analysis/cultural history/quasi-memoir, The Man Who Saved Britain, Simon Winder describes Roger Moore as “A faintly louche manikin…[who] was to spearhead the progressive degeneration of Bond over a further films,” going on to note the intersection of Moore’s tenure with a politically exhausted Britain in 1977: “[Bond] could comfort Britain for their loss of empire and status in the fifties, he could comfort Britain for the loss of its remaining prestige and the collapse of its industries in the sixties, he could offer a poignant and daft counterpoint to the early seventies, but nobody could do much for the utterly ruinous late seventies.” In an unintentionally evocative conclusion, he describes “The Spy Who Loved Me” as a “fantasy in the mind of a criminal lunatic or someone about to be executed.” Sinclair McKay, on the other hand, in his book The Man With the Golden Touch, links “Spy” to that year’s Silver Jubilee for Queen Elizabeth II, and places Bond’s self-spoofing action somewhere between the national nostalgia this anniversary engendered in England, and the scathing response to such nostalgia by the punk of the Sex Pistols, with 007 “unforgettably skiing off a dizzying cliff, free-falling a heart-stopping distance, and then, finally, cheekily opening a Union flag parachute.”

Perhaps the most interesting reading of the movie comes from Steven Jay Rubin’s detailed collection of production histories, “The James Bond Films,” when he’s describing Ken Adam’s genius for “atmospheric quality,” and notes “a particular ability to combine a feeling for drama with a spontaneous sense of fun.” He quotes Adam on his continuity sketches: “In a Bond film, we create the design of the film as we go along. We start out with a basic storyline, and as location ideas and stunts come our way, we develop the finished film.” This working method suggests that Winder’s description of “Spy” as a story told by a madman is not far off the mark, nor a bad thing—it’s filmmaking (and, perhaps, film viewing) defined by a kind of drift, and anchored by the face and charm of Roger Moore.

It says a lot about “Spy”’s aesthetic that its best action sequence is also its best moment of sustained slapstick. Bond and Amasova have just left Stromberg’s underwater laboratory in Sardinia, and as they drive through the hills, a series of Stromberg’s hit-men and women try to take the two spies out. First a motorcycle with a missile sidecar, then Jaws in a sedan, then henchman Naomi (Caroline Munro), the aforementioned winker in a helicopter overhead, who blasts them with machine guns. As one team of bad guys is taken down, the next sets out with the methodical determination of a violent, very funny Chuck Jones cartoon: at one point, Amasova gasps, and Bond deadpans, “Oh, no—don’t tell me…” without even giving a backward glance at their pursuers. The sequence is a a triumph of stunt-work and staging, where vehicles move in a ballet that might have made Hal Needham jealous.

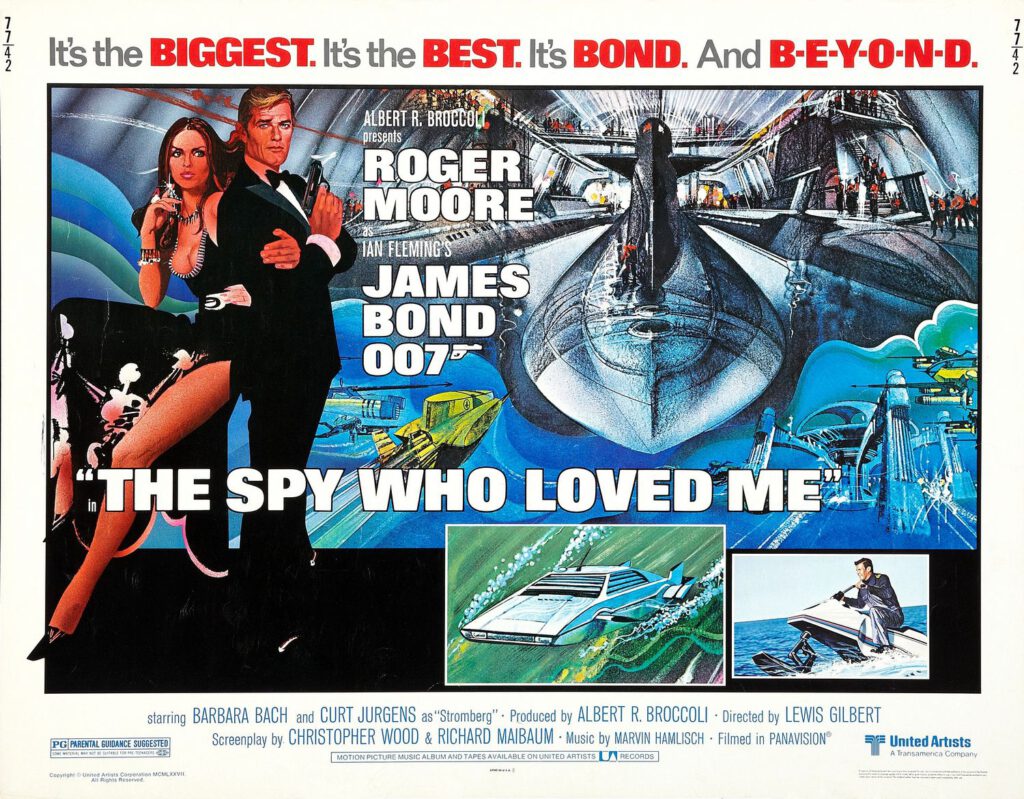

That makes Moore’s job all the more important: seen in inserts between the mayhem, his face has to register determination without breaking its sangfroid. Moore’s was always the poshest and snobbiest Bond, but where the stripped-down looks of “Live and Let Die” and “The Man with the Golden Gun” left that stylishness hanging out with nothing to respond to, the larger-than-life craft of “Spy” (as its posters said, “The BIGGEST. The BEST. Bond and BEYOND”) is the perfect place setting for his widening eyes and raised eyebrows. As he speaks to Amasova in the car, his body turns slightly to shift gears, but his face remains forward, chin jutting out, stirred but unshakable. Its almost theatrical stillness gives us something to hang on to amidst the explosions and the Marvin Hamlisch disco score, and his musical voice (“Can you swim?,” he asks Amasova cheerily) makes the prospect of flying into the ocean in an automobile sound fun, instead of entirely ridiculous.

Contrast that with how serious he is in the film’s climax, when he and a group of American and English sailors must defuse the detonator of a nuclear warhead. Moore’s furrowed brow and bright eyes are his secret weapon in scenes like this (there’s a similar one in 1983’s “Octopussy”): he’s an actor who does his best work in close-ups, and here his brow and stiffened cheekbones register determination, while his eyes capture Bond’s fear (and his attempts to stay focused in spite of that fear). His body remains remarkably still in the scenes medium and long-shots: in contrast to the lightning-quick physicality of a Connery or Craig, Moore’s is a Bond who waits—pensive, observant, disciplined.

Finally, the witty and the stoic come together in a nightclub in Egypt, where Bond formally meets Bach’s Anya Amasova for the first time. Moore enters the scene in long shot, framed against the pillars and tiles of the entrance way, and wearing a tuxedo; he moves smoothly, but his arms hang and slightly sway in such a way as to suggest they’re ready to pull a gun or strike out at a moment’s notice. He sits at the bar, and his left eyebrow cocks up when he spots Amasova in the doorway (his lip, meanwhile, cocks down, the two ends of his face fighting over approval and disapproval at once). Always the English gentleman, Moore meets her in the doorway, offers to buy her a drink, and addresses her as “Major Amasova,” to indicate that he knows who she is. She, too, is familiar with him, and as they sit at the bar, they play a game of one-upsmanship over each other’s dossiers and drink preferences. Moore’s head tilts towards and away from Bach, a kind of push-pull of entendre and withdrawal as the two get to know each other. Framed in two shot, we’re able to see Amasova’s face as she verbally pokes him, and Bond’s grimaces and tiny, clasped finger gestures in response.

When Amasova gets to the matter of Bond’s late wife, the camera cuts to an over-the-shoulder shot of Moore, whose eyes shoot down as he bites his lips; his eyebrow raises, but it’s an unforced response of pain and disgust, rather than the signal of a joke it so often is in the film. Moore’s voice flattens and becomes a bit hoarse, as if his poshness is scraping against a rock. “All right, you’ve made your point,” he says, voice rising on “made” in order to cut the subject short. “You’re sensitive,” Amasova says, her own voice registering surprise. “About some things, yes,” Moore’s Bond responds.

It’s a striking moment, not only for its callback to an earlier Bond film (something the Bonds of the seventies did only rarely), but for the way it functions as Moore’s authorial signature. Amidst the decoder watches, ski-pole guns, and other fun gadgets of “The Spy Who Loved Me,” it’s easy to lose track of Bond as a human being, an interpretation which the movie’s satire and Moore’s own self-deprecation in interviews often reinforced. But here is a journey from style to wit to character, all in a minute-and-a-half. “You’re sensitive.” “About some things, yes”—the movie will end with Anya and James popping champagne in a Stromberg escape pod and (as Bond says in the film’s final line) “keeping the British end up,” but it won’t entirely shake the pathos of this moment. Far from the “faintly louche manikin” of Winder’s nightmares, Moore’s performance in “The Spy Who Loves Me” takes a tawdry, depleted form (to paraphrase Kael) and makes something elegant out of it.