“Surprise…Beatles Good!” brays the newspaper headline. I still have the article. It’s taped in a scrapbook I started keeping around my 12th birthday in 1963 to retain ads and articles about my favorite movies, e.g. “Lawrence of Arabia” or anything starring Elvis. By early 1964, though, the scrapbook had morphed into a mostly-Beatles compendium. Not that I had lost my fascination with movies, I’d just encountered a new obsession. Then, in the summer of ’64, came the film that fused the two passions in a way that would shape the next several decades of my life.

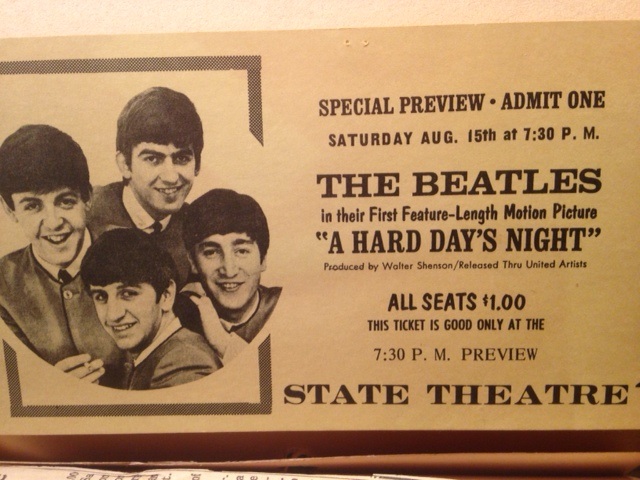

That scrapbook still contains my souvenir ticket to the Raleigh premiere of “A Hard Day’s Night,” on August 15, 1964. The movie had been greatly anticipated by the likes of me, to say the least. The soundtrack songs were all over the radio, and the old downtown movie palace was packed. What do I remember about that show? The girls screamed when the film started, as TV had taught them to do. But then they quieted down, because everyone wanted to hear the Beatles talk. And, like Garbo, talk they did.

Not that they were always easy to understand. Watching the film a half-century on, I get almost every line of dialogue in it. But American ears in 1964 were not used to British voices: crisp BBC intonations may have been intelligible, but working-class Liverpool accents could verge on the impenetrable. United Artists was worried enough about this to suggest looping the dialogue, but in the end it didn’t matter. The linguistic muddiness and unfamiliar slang only added to the film’s air of exotic authenticity; and in any case, everything was crystal clear whenever the boys began to sing.

Looking back today, only one other element strikes me as notably different than it did in 1964. On first viewing, I was not at all crazy about the character of Paul’s grandfather (vinegary Wilfred Brambell), who seemed a needless, annoying gimmick too often obstructing our view of our idols. I suppose I was an incipient critic even then, because I would have suggested eliminating the old geezer altogether. Now, I not only appreciate scripter Alun Owen’s clever use of granddad to spark conflict among the Beatles and their handlers, I think the chaotic comedy the old guy provokes (he’s an unregenerate Irish rebel, after all) is some of the drollest in the film.

Of course, age was a factor not only in the film’s story but in its initial reception too. “A Hard Day’s Night” famously opened the eyes of older people (i.e., those over 20) to the brilliance of the Beatles. That “Surprise…Beatles Good!” headline was typical of the condescension displayed even by media supposedly dedicated to exploiting the latest fads. My reaction to that story was a mix of amusement, contempt and vindication. How could old people be so stupid as not to have realized the Beatles’ genius instantly, as we 12-year-olds had? “A Hard Day’s Night” didn’t surprise me in the least. Paul’s granddad aside, it was exactly what I expected it to be: a movie that felt like a miracle.

Because the Beatles themselves seemed touched with the miraculous from the first. They appeared as if out of nowhere (which England effectively was, in terms of American teen culture). One day nobody had heard of them, the next their music was everywhere and, in another flash, they were drawing record-breaking TV audiences on the Ed Sullivan show. Everything about them seemed startlingly different and new: the sound, the clothes, the hair, the gags and irreverence. Though the press would try to explain that they’d been cleaned up visually by manager Brian Epstein and aurally by producer George Martin, it was clear to us fans that the Beatles were entirely self-created. And part of their miraculous nature involved attracting just the right helpers at the right time.

Which happened with “A Hard Day’s Night” too. Could the Beatles produce, write and direct a feature film? Of course not. What I expected, as a true believer in this mysterious new phenomenon, is that they would again find the perfect collaborators. And so they did. In late 1963, as the Beatles were about to explode from Europe onto the world stage, they connected with two expatriate Americans, producer Walter Shenson and director Richard Lester, who brought aboard Welsh TV writer Owen. With United Artists giving them virtually carte blanche – a minor miracle in itself – these three were able to create a film as striking and original cinematically as the Beatles were musically.

Its peculiar alchemy involves fusing the real and the fantastical, the documentary and the dream-like. The filmmakers’ root concept was to chronicle a day in the life (to coin a phrase) of the Beatles, in which they travel by train from Liverpool to London, encounter various mishaps (often involving granddad) and adventures, always pursued by screaming fans, and finally tape a TV concert. For us real-life fans, this had the great appeal of ostensibly taking us into the Beatles’ actual lives (for Americans like myself, it also ushered us into a Britain we’d never seen). But of course, it was about as realistic as a comic book. Lester, Owen and the Beatles all shared a taste for the brainy absurdist comedy of the Goon Show (and later exemplified by Monty Python), and their story gives us not only an exuberantly idealized version of Beatlemania, but also one that’s shot through with satiric and surreal sidelights.

Regarding the film’s innovative visual style, Lester has understandably cited the influence of the French New Wave. One must also note the impact of new, lightweight cameras, faster film stocks and recording equipment on advertising and the other “new cinemas” of Europe, including Britain’s. No doubt many U.S. critics knew these precedents. But as I was years away from seeing my first foreign film, the energy and intimacy of Lester’s often hand-held shooting style (executed in beautifully lit b&w by cinematographer Gilbert Taylor) were all stunningly new to me. When Andrew Sarris called the film the “’Citizen Kane’ of jukebox musicals,” it was not just an amusing compliment. With its complex, inventive orchestration of swish pans, dramatic zooms and close-ups, varying film speeds and much else, “A Hard Day’s Night” may indeed have introduced as many stylistic novelties to mainstream audiences as “Kane” did.

Naturally, all of these eye-grabbing techniques would have counted for little if the four guys at the film’s center hadn’t pulled their weight, but the Beatles served up a great batch of new songs and proved to be superb, natural comic actors. (Again, older people were surprised at how good they were, while we kids expected nothing less.) Their screen personas built deftly on those they’d already established in the media (romantic Paul, acerbic John, wry George, goofy Ringo: the latter always the most popular Beatle is early polls), but watching the film recently made me wonder if the subtle power relations within the band influenced the way Lester and Owen apportioned their screen time. Was it because John and Paul were the principal songwriters and perceived leaders of the group that they were given the least to do (Paul least of all), while Ringo and George were each awarded separate extended scenes of their own?

That question would not have occurred to me in 1964. At the time of “Let It Be” five years later (a half-decade that felt like a millennium in pop culture history) the fissures within the band were visible for all to see. But in the first year of year of global Beatlemania the fab ones appeared a glorious unity: best friends, ideal musical partners, a grinning, weaving four-headed Beatlemonster. The important tensions in “A Hard Day’s Night” are between that unity and the world that keeps impinging on it, with demands, distractions and no end of annoyances. Lester and Owen have noted that the film’s early scenes are intentionally claustrophobic in mood, as a way of setting up one of the most exhilarating scenes in all cinema, when the Beatles burst out of the TV studio onto a playing field and Lester’s cameras frenetically leaping cameras record their joyous dance of freedom as “Can’t Buy Me Love” rocks out on the soundtrack.

Joy and freedom: those feelings were what the Beatles brought to an astonished world when they appeared as if by divine fiat in the early ‘60s, and they’re the same feelings that “A Hard Day’s Night” perfectly preserves for those too young to have experienced Beatlemania first-hand. Fifty years later, I watch the film and feel about it almost exactly as my 12-year-old self did. That would be astonishing, perhaps, if I’d not learned long ago to expect such serendipitous miracles from the Beatles.

Note: To celebrate its 50th anniversary, “A Hard Day’s Night” returns to theaters next week. This week brings the release of a DVD/Blu-Ray edition of the film from the Criterion Collection, featuring a new 4K digital restoration approved by Richard Lester with three audio options. Up to Criterion’s usual high standards, the package also contains a booklet with an essay by critic Howard Hampton and a number of extras; some of these are vintage documentaries about the film, but two of the best are new: an interview with author Mark Lewisohn tracing the Beatles’ history up to “A Hard Day’s Night,” and “Anatomy of a Style,” an astute analysis of Lester’s and editor John Jympson’s techniques.