Q. I’m puzzled by the seeming moral indifference to the subject matter of “8mm.” The “snuff film” theme seems to have barely raised any eyebrows (yours included), in sharp contrast to the recent uproar surrounding “Lolita.” Why is the latter considered untouchable, while the former attracts an audience outwardly apathetic to its much darker subject? (George Patrice, DeKalb, IL)

A. The remade “Lolita” was indeed shown on cable TV to less furor than might have been anticipated. But the answer to your question hinges on this fundamental point: A film is not moral or immoral because of its subject matter, but because of how it treats its subject matter. I believe that “8mm” dealt with its subject responsibly; I wrote, “It deals with the materials of violent exploitation films, but in a non-pornographic way; it would rather horrify than thrill.” Also, of course, morality resides in the viewer, not the film, which is why censors believe it is correct for them to view dirty movies.

Q. The wire services recently carried a story reporting that a study has revealed that the average G-rated film had five times the gross profit and a 31 percent higher return on investment than the average R-rated film. What is your take on this? If G rated films make more money, why don’t we see more of them? (Paul Chinn, Rochester, MI)

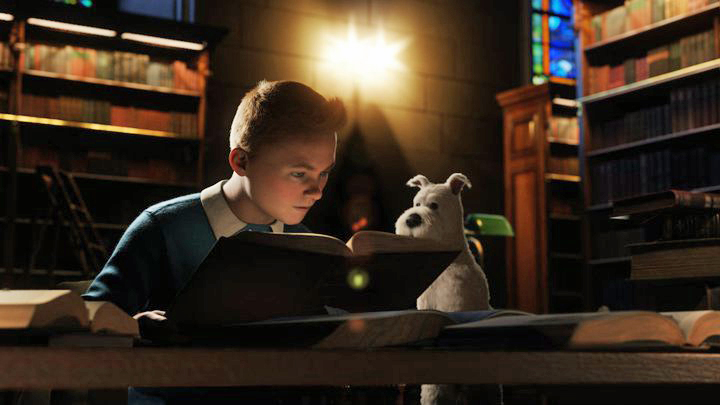

A. This survey from the conservative Dove Foundation recycles a statistical error that was discredited by Variety when Michael Medved publicized a similar claim several years ago. It is based on a simple but subtle flaw: A handful of films dominates a small category, and that leads to misleading results. Relatively few G-rated films are released in a year (most family films are PG or PG-13), and the category is dominated by the hugely profitable Disney animated cartoons, skewing the statistics. So okay, why don’t studios make more animated features? They’d love to, and Dreamworks, Warner Bros. and Universal have all jumped into the genre, with titles like “Antz,” “Space Jam” and “The Prince Of Egypt.” They’ve had success, but not the huge grosses that Disney enjoys. It’s not that easy to make an animated megahit.

Q. “Stepmom” has a line that made me cringe. When Ed Harris is telling Susan Sarandon that he’s marrying Julia Roberts, the waiter comes over to the table and says to Harris, “Can I get anything for your wife?” Sarandon abruptly responds “I am not his wife!” Now this was obviously done to get an audience reaction, and the writers must have thought they had a terrific tag-line. But the fact is that it just doesn’t work. I have been to many restaurants, and never, ever have I heard a waiter assume that the person you are with is your spouse. That’s just plain dumb, and was created to get an “ooooohhhh” out of the audience. Well I say “booooo.” (Bradley Richman, New York City)

A. Yeah, waiters learn to be canny about not making any assumptions about the relationships between customers (“Another drink for your parole officer?”)

Q. Why is it that the Academy only seems to remember movies that were released later in the year? I thought for sure that either Holly Hunter or Queen Latifah would have been nominated for “Living Out Loud” and both were overlooked. This has happened in prior years and I was curious as to why that consistently happens. (Suzanne Rudolph, West Chester, PA)

A. I’ve written before about the Academy Attention Span problem: Movies released more than four months before year’s end are penalized. But “Living Out Loud” came out in November, and so it doesn’t fit that theory. Okay, here’s another reason: It was not a big box office hit. Although there are exceptions, the Oscar voters tend not to vote for movies that didn’t make a lot of money. They don’t like to embrace box office mediocrity because they’re afraid it may be catching. The Independent Spirit Awards, held in a big tent on the beach in Santa Monica on the day before the Oscars, has no such superstition, and indeed this year’s awards are being hosted by Queen Latifah. The live broadcast is at 3:30 p.m. (CST) on the Independent Film Channel, with repeats at 8 p.m. CST on Bravo and 9 p.m. CST on IFC.

Q. I have become so strident on the topic of people who talk during movies that many of my closest friends refuse to go to a theater with me. I almost always end up rudely and profanely telling someone to shut the hell up. My most recent episode was at “Saving Private Ryan,” where a middle aged woman behind me felt the need to point out several times during the invasion of Normandy that Tom Hanks was bleeding from the ears. I finally wheeled around and snarled “DAMMIT, I WANT QUIET BACK THERE!” Silence fell. Some might suggest I ask politely, but I’ve discovered it doesn’t really work. However, my more direct approach will almost certainly get me beaten up eventually. So how do we bring silence to the average movie theater? I’ve come up with an idea. Since your average multiplex has about 8 zillion screens, why don’t they designate “talking” and “non-talking” theatres? Those who want to talk and crunch popcorn and screw around with laser pointers can gather with their brethren, and those of us who want to watch the movie we paid to see can watch in peace. (W. Gamache, Calgary, Alberta)

A. This is an excellent idea. You could be employed to toss a percussion bomb into the talking theaters from time to time.

Q. Clarifying your article on the late, great Stanley Kubrick: You stated that “A Clockwork Orange” was banned in Britain, but the film was never “banned.” That is, there was never any successful action to legally prevent it from being shown. Rather, Kubrick himself pulled the film from release in Britain, and never allowed it to be shown there again. Apparently, he was disturbed by acts of violence that occurred at or near theaters showing the film, or perhaps violence that was attributed to the perpetrators’ having seen the film. Despite the film’s absence from screens and video shops, it has become a sort of cult classic over there. (Pat Haly, Vallejo, CA)

A. You are quite right. “A Clockwork Orange” was released in the UK, but in 1973, as The Daily Telegraph reported, “The film’s carefree use of violence–notably a rape scene accompanied by singing and laughter–caused considerable controversy, and after a number of copy-cat assaults Kubrick invoked his contractual right to withdraw the film from public screening in Britain.” There is press speculation that it will now be reopened in Britain.