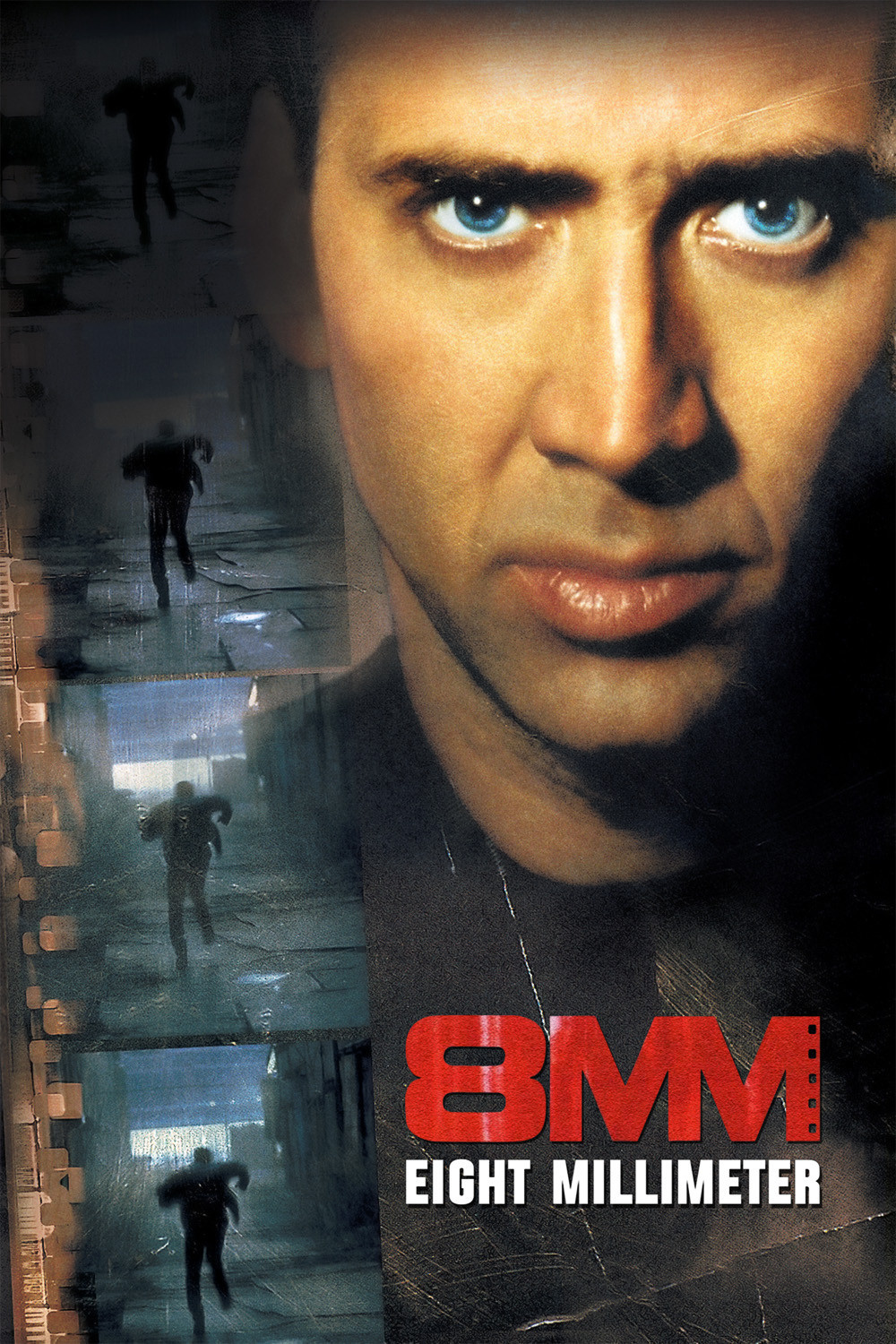

Joel Schumacher‘s “8mm” is a dark, dank journey into the underworld of snuff films, undertaken by a private investigator who is appalled and changed by what he finds. It deals with the materials of violent exploitation films, but in a non-pornographic way; it would rather horrify than thrill. The writer is Andrew Kevin Walker, who wrote “Seven,” and once again creates a character who looks at evil and asks (indeed, screams), “why?” The answer comes almost at the end of the film, from its most vicious character: “The things I do–I do them because I like them. Because I want to.” There is no comfort there, and the final shots, of an exchange of smiles, are ironic; Walker accepts that pure evil can exist, and that there are people who are simply bad; one of his killers even taunts the hero, “I wasn’t beaten as a child. I didn’t hate my parents.” The movie stars Nicolas Cage as an enigmatic family man named Tom Welles, who works as a private investigator and comes home to a good marriage with his wife (Catherine Keener) and baby. He specializes in top-level clients and total discretion. He’s hired by the lawyer for a rich widow who has found what appears to be a snuff film in the safe of her late husband; she wants reassurance that the girl in the film didn’t really die, and Welles tells her snuff films are “basically an urban legend–makeup, special effects, you know.” The film follows Welles as he identifies the young woman in the film, meets her mother, follows her movements, and eventually descends into the world of vicious pornographers for hire, who create films to order for a twisted clientele. Joel Schumacher has an affinity for dark atmosphere (he made “The Lost Boys,” “Flatliners” and the two of the Batman pictures). Here, with Mychael Danna’s mournful music and Robert Elswit’s squinting camera, he creates a sense of foreboding even in an opening shot of passengers walking through an airport.

The purpose of the film is to take a fairly ordinary character and bring him into such a disturbing confrontation with evil that he is driven to kill someone. Tom Welles, we learn, went to a good school on an academic scholarship, but although his peers “went into law and finance,” the rich widow’s attorney muses, “You chose surveillance.” Yes, says Welles: “I thought it was the future.” Mostly his work consists of tailing adulterers, but this case is different. He meets and talks with the mother of the girl in the film, traces her movements to Hollywood, and then enlists a guide to help him explore the hidden world of the sex business.

This is Max California (Joaquin Phoenix), who once aimed high but now works in porno retail; the film suggests that the Los Angeles economy takes hopeful young job-seekers and channels them directly into the sex trades. Through Max, Welles meets Eddie Poole (James Gandolfini), the kind of guy who means it when he says he can get you whatever you’re looking for. And through Eddie, they meet Dino Velvet, a vicious porn director played by Peter Stormare–who was the killer who said almost nothing in “Fargo,” and here creates a frightening set of weirdo verbal affectations. The star of some of his films is Machine (Chris Bauer), who doesn’t like to remove his mask.

We expect Welles to get into danger with these men, and he does, but “8mm” doesn’t treat the trouble simply as an occasion for action scenes. There is a moment here when Welles has the opportunity to get revenge, but lacks the will (he is not a killer), and he actually telephones a victim and asks to be talked into it. I haven’t seen that before in a movie, and it raises moral questions that the audience has to deal with, one way or another.

I know some audience members will be appalled by this film, as many were by “Seven.” It is a very hard “R” that would doubtless have been NC-17 if it had come from an indie instead of a big studio with clout. But it is a real film. Not a slick exploitation exercise with all the trappings of depravity but none of the consequences. Not a film where moral issues are forgotten in the excitement of an action climax. Yes, the hero is an ordinary man who finds himself able to handle violent situations, but that’s not the movie’s point. The last two words of the screenplay are “save me,” and by the time they’re said, we know what they mean.