Q: I just saw “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban.” You are not the first person to express concern that the children may soon be too old for their parts. I disagree. The children in the books are growing older, and by the time book seven is written, Harry and his friends should be about 17 or 18. The actors may be a couple of years older than their characters, but I’m sure they’ll be believable as always.

And you’re right, there is “less than whimsical violence” to come, if the movies stay true to the books. If you think this one was dark, wait until the fourth one; it is very disturbing, and the fifth book is downright depressing. It almost makes me dread the last book.

I will agree about the “murky plotting.” The movie failed to explain that Black, Pettigrew, and James Potter were all animagi. It failed to explain why they became animagi, why Snape had such loathing toward them, and why Harry’s Patronus resembled a stag at the end. It also failed to explain Lupin’s, Potter’s, Pettigrew’s and Black’s relationship to the mysterious Marauder’s Map. These points are pretty important to the story, and to Harry’s growth as a wizard. I’m predicting a lot of 12-year-olds will be extremely unhappy about this. Susan Warren, Montgomery, Ala.

A: My belief has always been that the director’s first responsibility is to his film, not to the book he is adapting. For me, the problem was not that Alfonso Cauron did not follow the book, but that on its own terms, the plot seemed to lose its way toward the end.

Q. In your article about “Fahrenheit 9/11” at Cannes, you quote Michael Moore’s film that, when informed of the second attack on the World Trade Center, President Bush “incredibly remained with the students for another seven minutes, reading from the book, until a staff member suggested that he leave. The look on his face as he reads the book, knowing what he knows, is disquieting.” Apparently you believe this version of events. Does Moore identify a source? Or is his word good enough for you? If that is the case given that “Bowling for Columbine” was riddled with half-truths and lies that even he corrected on the DVD, why would you assume this movie to be fact? Jim Carmignani, Naperville

A. Bra Grier of Omaha writes: “Here’s the video of Bush in the classroom for five minutes after being told ‘America is under attack.’ Unfortunately, the video ends before the president does.”

To see it for yourself, go to www.thememoryhole.com/911/bush-911.htm

Q. You state you had a duty to objectively review “Fahrenheit 9/11” and judge its merits sans its political agenda. Fair enough. But do you think a well-made, funny and nasty anti-Chirac, pro-Bush documentary will be winning the Golden Palm at Cannes in this century? Or how about a scathing expose of European anti-Semitism, or a documentary where the camera stalks the authors of those best-selling French books about how the CIA and Israel were behind 9/11? Would these films, if made as well as Moore’s film, be applauded by the Cannes set? Andrew Weber, Merrick, N.Y.

A. No, probably not. As I mentioned on “Ebert & Roeper,” although all nine members of the Cannes jury individually said at the press conference that they made their decision based on filmmaking, not politics, I believe it is realistic to believe it was based on both. That said, don’t make the mistake of thinking the “French” honored “Fahrenheit 9/11.” The jury did, and only one of its nine members was French. There were four American members, and the others were from Finland, Hong Kong, Belgium and the United Kingdom.

Q. There was a controversy on the set of Lars Von Trier’s upcoming movie “Manderlay,” regarding the actual onscreen killing of a donkey, which resulted in John C. Reilly walking off the picture. How you feel about the ethics of this situation? Is the killing acceptable since there was a vet on the set and the donkey was reportedly old and sick? How about the scene in “Apocalypse Now,” where Kurtz’s army slaughters the cow? Though I’m not an animal lover or a vegetarian, there’s something about actually killing animals in a fiction film that doesn’t sit right with me. Matt Singer, New York City

A. Millions of animals are killed every day so we may eat them, and yet we’re sentimental about individual animals. There’s currently hysteria in Illinois about the killing of horses to supply horsemeat (which is shipped to France). Most of the opponents of horsemeat have no trouble with the killing and eating of cows, pigs, chickens, etc. It seems absurd to get worked up about one species and not another.

But your question involves the killing of animals for art, not food. I feel if you accept the killing of animals at all, then requiring the animal to be killed for food but not for art is inconsistent.

That said, how should we respond to the Korean film “Old Boy,” which played at Cannes and had a scene where a live octopus was eaten by one of the characters. In his acceptance speech, the film’s director thanked four octopi who died in the making of the film.

Q. When I saw the original “The Stepford Wives” (1975), I found the ending disturbing and shocking (in a good way). I recently saw a preview for the upcoming remake, and it literally tells the entire story, ending included. Why would the studio want to rob audiences of that moment of realization? It really made me mad. How can we stop this sort of ad? Eric Olsen, Pompton Lakes, N.J.

A. You can’t. The Answer Man has explained this before: The marketing people, whose interest in a movie is focused entirely on selling it, have the same philosophy as salespeople in grocery stores who offer you a piece of cheese on a toothpick. After you have sampled it, you know everything about the cheese, except what it would be like to eat the whole thing. Same with trailers that summarize the whole movie.

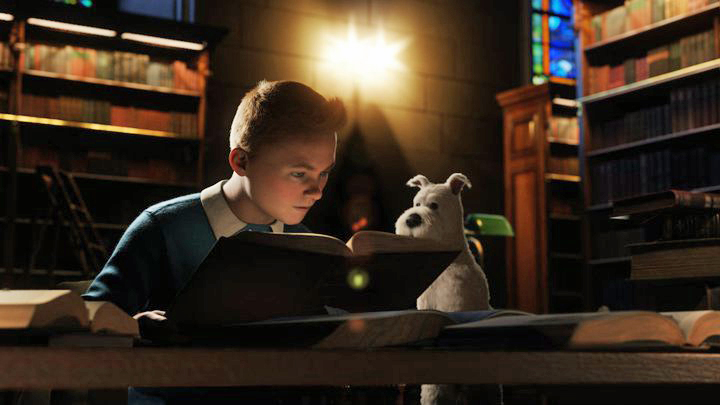

Q. Here’s what computer-generated images rob from the filmgoer.

1) A movie is no longer a documentary of itself. When you watch the battle scenes in “Lawrence of Arabia” or “Ran,” or the train crashing at the end of “The General,” they work not only as story, but as logistics and direction; what you see had to really happen. In “Troy,” when a shot shows more ships than there were Trojans, it seemed like a satirical comment on CGI.

2) CGI is too clear. In any frame showing a computer-generated image, its clarity is greater than the filmed scene into which it is inserted. Even in an animated film like “The Triplets of Belleville,” small CGI touches such as a model of the Eiffel Tower are much finer than the surrounding drawn cel. Unless you are a programmer or computer game aficionado, CGI holds no magic. Mike Spearns,St. John’s, Newfoundland

A. Jean-Luc Godard said, “The cinema is truth at 24 frames a second, and every cut is a lie.”

That’s why some directors are fond of long takes; the actors are sharing real time with the audience. The movies have always used special-effects trickery, like painted backdrops, matte drawings and optical shots, but the people were generally real; now CGI blends reality and invention so seamlessly that movies lose conviction and have the same freedom as a cartoon over laws of time, space and gravity.