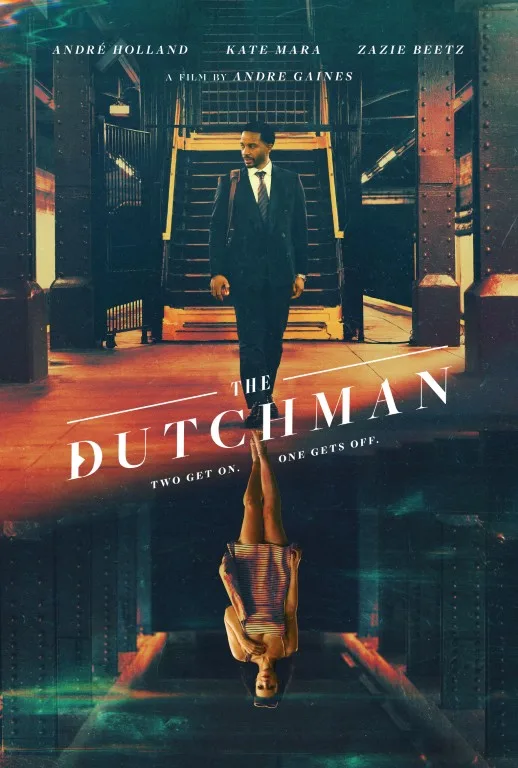

Director Andre Gaines has spent most of his career making nonfiction films about Black historical figures like Olympic runner Jesse Owens, baseball legend Jackie Robinson, and boundary-breaking comedian Dick Gregory. In his first foray into fiction filmmaking, Gaines chooses to tell the story of a Black man who exists only on the page.

“The Dutchman,” based on the play by writer and poet Amiri Baraka, follows Clay (André Holland) as he faces trouble with his marriage. His wife Kaya (Zazie Beetz) has been unfaithful, and though he chose to stay with her, Clay is struggling to forgive and move on. In couples therapy, Clay zones out as his therapist, Dr. Amiri (Stephen McKinley Henderson), watches him with a knowing stare. After the session, he offers Clay a copy of Dutchman to read, but his anxious patient declines. Nevertheless, when Clay steps onto the uptown 1 train to Harlem that evening, the play begins, and the narrative overtakes him. It helps that he and the protagonist of Dutchman have the same name. It’s as if he were cosmically gifted the starring role.

Dutchman was adapted for the screen only once before. The 1966 film was made by Anthony Harvey, a white British director most known for the film he made two years later–“The Lion in Winter.” Baraka wrote the screenplay, adapting his own work at a time when that was rare for radical Black writers. The film took place entirely on a subway car, as Lula (Shirley Knight) approaches Clay (Al Freeman Jr.) with intentions to seduce and antagonize him. She gets comfortable immediately, taking off her shoes and eating a seemingly endless supply of apples from her bag. She offers one to Clay, and he eagerly takes the forbidden fruit. They sit dangerously close to each other on the train, with their thighs touching. Eventually, Clay’s legs are open, and the energy turns erotic.

But Lula’s racism adds another layer of perversion, as she taunts Clay for being attracted to her at all. She calls him an Uncle Tom more than once, taunting him for his proper clothes and polite, cultured way of speaking. Clay allows Lula to grill him on his personal life and history, taken in by her surprisingly accurate observations. Encouraged by his own internal struggle with Blackness, Clay is excited by Lula and her brazen whiteness. But after a while, he begins to tire of her constant provocations, and their flirtation erupts into violence.

In this new film, Lula (Kate Mara) and Clay get off the train and consummate their flirtation. But their tryst is portrayed sans eroticism–Lula is like a demon feeding on Clay’s life force, exploiting his weakness and indecision. Lula is a loud, broad antagonist who uses her body and voice as a weapon. In her apartment and out on the street, Lula screams whenever Clay tries to get away from her. Unlike the Clay of the previous film, he’s not drawn in by her many provocations. Their dynamic is purely antagonistic, with Lula quite literally trying to separate Clay from his community.

Her intentions are made most obvious once the pair arrives at a political fundraiser in Harlem for Clay’s friend Warren (Aldis Hodge). Faced with the embarrassment of Lula’s presence in front of his wife and all his friends, Clay manages to rise to the occasion. He gives a speech introducing Warren and emphasizing the importance of the Black community thriving. Clay’s momentary triumph makes Lula more determined to finish the play with its intended ending—Clay’s murder.

As the night wears on, Clay begins seeing scenes from the 1966 film, including the part where Knight’s Lula stabs Clay to death while the other riders—both white and Black—just let it happen. Knowing what’s coming, Clay tries to get the upper hand, insulting Lula and her empty provocations. Dr. Amiri lurks in the shadows, interfering one moment and gone the next.

There’s a mystical element to presence—Henderson is playing a magical, fictional version of Baraka using Clay to act out a different ending to his play. But what is the significance of returning to Dutchman after 60 years? What about our current times suggests a need for renewed interest in Clay and his struggle between Black and white worlds? That question hangs over the entire film.

In 2019, Rashid Johnson’s “Native Son” elicited similar criticisms. Baraka and Richard Wright wrote about being a Black man in response to the times they lived in. “Native Son” was adapted for the screen for the first time in 1951, and, in a manner similar to “Dutchman,” the film was made by a white man unburdened by America’s particular racial history. French director Pierre Chenal adapted Wright’s novel and cast the author in the lead role.

Both films were released during a time when Black male identity in popular culture was slowly being redefined. But now, in 2026, we have stars like Holland who remain dedicated to portraying the modern Black man in all his complexities. It’s hard to see a need to return to the well here, especially considering “The Dutchman’s”s greatest weakness–a complete and total disinterest in Black women. By expanding the play’s world, Gaines opens himself up to new scrutiny. Beetz does the best she can with a thinly drawn character, but it’s hard not to wonder what “The Dutchman” would look like if Gaines showed any real interest in her.