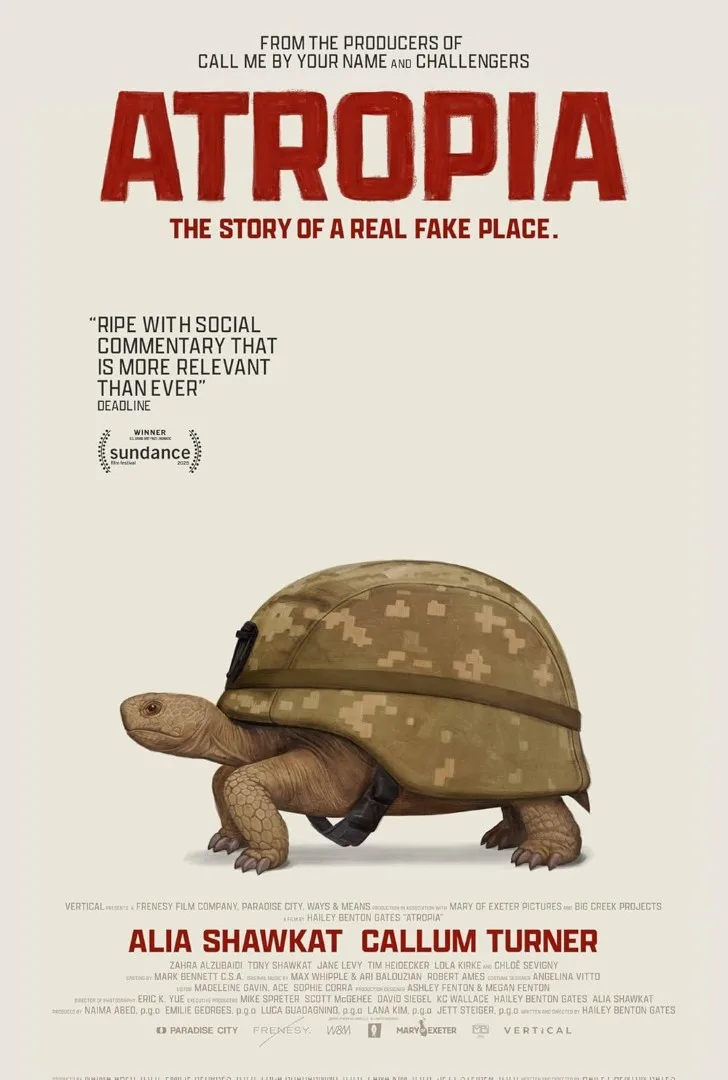

Wartime satires skewering the vagaries of American militarism are nothing new, nor are films that contrast the theater of war with actual theater (“Tropic Thunder,” “Wag the Dog“). But Hailey Gates’ “Atropia” uses as its setting the real-life wartime simulator, located in the California desert just a few dusty steps from Hollywood, in which the military trains new cadets to handle situations in whatever country we happen to be fighting at the time. In 2006, when this film is set, that’s Iraq; Gates’ feature, then, expanded from her 2020 short “Shako Mako,” finds plenty of droll fun in its early stretches lampooning not just the violence of the American war machine, but the kind of pop-culture conceptions and cultural signifiers we associate with the War on Terror. Shame, then, that the film can’t quite sustain its focus on that particular hurt locker.

What works best about “Atropia” is when Gates leans hard into its simulated war play as a means of exploring the inherently exploitative gaze of war filmmaking. Take the opening scene, in which we see the kind of deployed-soldiers-in-peril scenario we’ve witnessed even as recently as Alex Garland’s “Warfare“: Except this time, the wailing Iraqi woman (Alia Shawkat) crying over an exploded dead body drops character, and the Orientalist facade falls away as if a director had just called “cut.”

Shawkat plays Fayruz, one of many extras play-acting as Iraqis in “The Box,” Atropia’s current configuration to help fresh-faced recruits train for the horrors of the occupation of Iraq. She’s also, crucially, one of the few ensemble members with actual Iraqi heritage (most of the day players are Mexican, we’re told); her parents disapprove of her role in helping American soldiers invade their home nation, but as an aspiring actress, she sees it as her ticket to prospective stardom. To her credit, Shawkat is fascinatingly layered here, mining every gesture towards helping her fellow actors as somehow self-serving (as seen in her antipathy towards another extra who gets more attention despite, well, not speaking Arabic).

In this first stretch, “Atropia” shines as an appropriately droll dig at Hollywood’s eagerness to indulge in stereotype and morbid blood-letting for entertainment. We see flashy introduction videos that play up the jingoistic fervor of Atropia’s mission, and the milling-about between scenarios feels like the backlot of a Hollywood studio (“The thing about California is, she can play any part you want to play,” one character notes). Military higher-ups, here played by Tim Heidecker and Chloë Sevigny, function largely as casting directors, while special effects experts weigh which prosthetic legs amputees can use to resemble victims of IED explosions. One early stretch offers a delightful cameo from an A-list movie star who’s done these kinds of flicks before, interceding in the Iraq War LARPing to prep for a role in ways that highlight the flattening of violence into spectacle once translated into storytelling. The artifice is front and center, and “Atropia”‘s best gags come from the characters’ sheer commitment to such blatant, empty spectacle—all in service to a war we know, especially in retrospect, we should not be aging.

But Gates’ surer command of tone in the first half starts to stumble as Fayruz begins a curious infatuation with “Abu Dice” (Callum Turner), a white combat vet play-acting as an Iraqi while he awaits redeployment. The two strike a curious flirtation, which gives way in the early goings to some deliciously kinky rendezvous. (You’ll never think about a

Port-a-Potty the same way again.) It’s deceptively sweet at first, but in the latter half, it becomes clear that Shawkat and Turner don’t have nearly the chemistry they need to pull off this central romance, nor does Gates’ script give them interesting, cohesive enough things to do.

Instead, Gates waffles between reaching for more curious angles to take the (literal) theater of war, while awkwardly flitting back to Fayruz and Dice and their confused attempts to join, or flee, the experiment altogether. “Atropia”‘s sillier tone starts to drift as it takes these lovers a bit more seriously. Even so, without the groundwork needed to dig into these two, or the heat necessary to buy their romance beyond a few fetishistic encounters, it’s easy to feel adrift by the third act. In fact, these more direct plot elements seem to keep the film’s more pointed targets (such as American culture’s eagerness to manufacture consent for war by making it seem like exciting play) from getting the deeper treatment they deserve.

At the end of the day, “Atropia” feels like Gates gesturing vaguely at a few really interesting notions about the military-entertainment complex, and how it can bleed through into the people waging the actual war. We get closest to such insights when we focus on, of all people, the actual soldiers for whom this big production is being made: they’re kids, immature teens who spend their time jerking around and hiding just how scared they are to do the real thing. Because everyone knows this is, essentially, interactive theater (think Sleep No More meets “American Sniper“), these kids feel like bystanders in their own story. It feels like there’s more to explore there; instead, Gates entertains herself with surreal flourishes like an endangered Californian tortoise whose well-being offers the only true stakes anyone has to worry about in The Box.