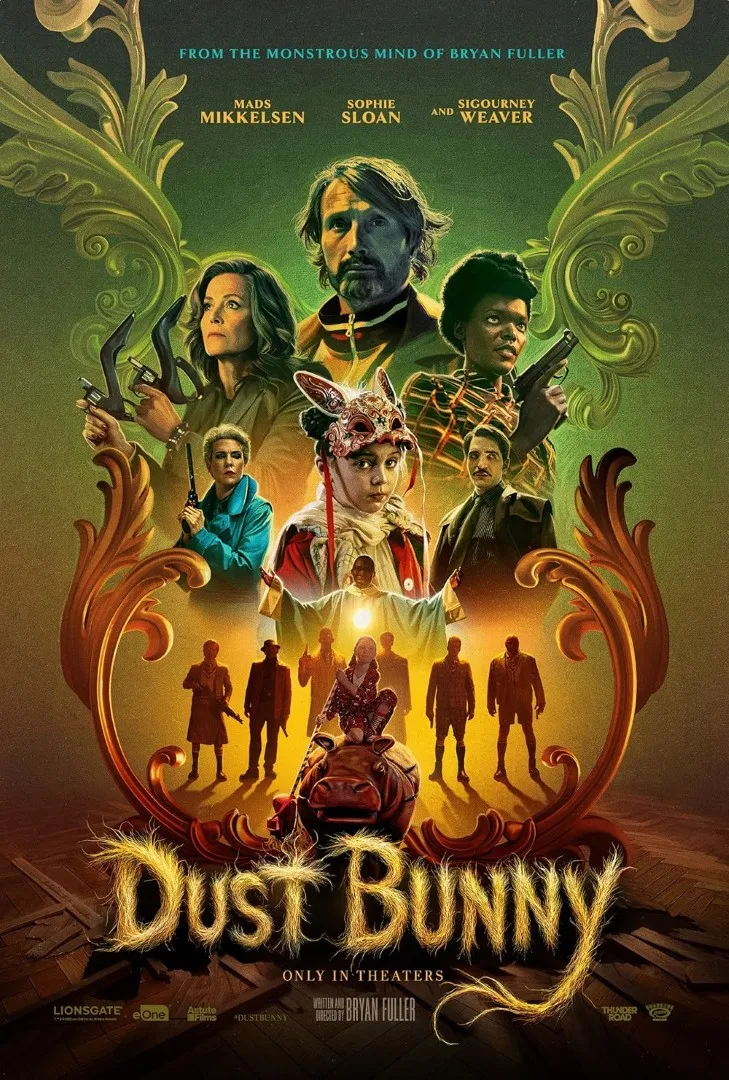

“Dust Bunny” is the directorial debut of Bryan Fuller. For the unfamiliar, Fuller is best known as a writer-producer for television, specializing in series that are visually striking and sometimes brilliant, but a little too demanding and peculiar (and up their own bum artistically, in the best way) to attract a large enough audience to justify their budgets. His CV includes “Pushing Daisies,” “Hannibal” (with the cannibal shrink played by this movie’s lead, Mads Mikkelsen). Fuller also oversaw the TV movie “Mockingbird Lane,” a pilot for a proposed hour-long comedy-drama reboot of the 1960s sitcom “The Munsters” that didn’t get green-lit as a series. And he was simultaneously the showrunner for the inaugural seasons of “Star Trek: Discovery” and “American Gods,” but left due to budget overruns on both series as well as difficulty handling two expensive shows at once.

“Dust Bunny” suggests that, cult TV hits notwithstanding, Fuller might’ve been altogether more successful in feature films, where ideas have to be contained by commercially approved running times (somewhere between ninety minutes and three hours) and whatever budget is available. This leads to a certain compact sharpness (at least in good movies) that’s more conducive to metaphors, visual symbols, allegorical touches, dream logic, ambiguity, and other stuff that mainstream TV audiences tend to resent. Fuller throws all those elements and more into his first feature.

“Dust Bunny” is set in a half-storybook, half-nightmare vision of New York. Its main character is a little girl named Aurora (Sophie Sloan) who’s convinced there’s a monster under her bed, but can’t get her parents to take her seriously. At the same time that she’s failing to convince her parents that their lives are in danger, Aurora begins spying on Mikkelsen’s character, who lives across the hall in Aurora’s apartment building, and slips out late at night with furtive expressions and a keen awareness of who’s watching him. He is never given a formal name. He calls himself Resident 5B, after his apartment number, or 5B for short, while the closing credits list him as “Intriguing Neighbor.”

The man is indeed intriguing to Aurora, mainly when she follows him to Chinatown and watches him defeat what appears to be a deadly shadow dragon manifested from a multi-segmented dragon puppet. Aurora steals a collection plate from the church and leaves it for 5B with a note asking if the amount is enough “to procure [his] services.” (When 5B asks the kid how she learned a word like “procure,” she says she got it from a Word of the Day desk calendar.) 5B shrugs off Aurora’s story, telling there’s no such thing as monsters, only monstrous people, and insisting humans murdered her parents—criminals, perhaps, or someone with a grudge. But we know there’s a monster because we saw it being born in the opening credits, and because the showrunner of “Hannibal” and “American Gods” isn’t going to make a movie about a little girl who says there’s a monster when there isn’t.

This is where “Dust Bunny” starts to re-frame and re-re-frame its story. 5B’s origins are never explained, but he could be an assassin himself, and he’s certainly a hardened veteran of many battles. There’s a character who might be his handler, or former handler, played by Sigourney Weaver, and some folks with guns and ninja skills and/or hazy agendas, including David Dastmalchian in a note-perfect supporting performance as a skilled, relentless, but overconfident killer, and Sheila Atim as an unflappable lady who claims to be from Child Protective Services but keeps talking to people through a hidden earpiece.

“Dust Bunny” initially comes across as derivative and, in some ways, clichéd. There are moments where it seems to think it’s more ingenious than it is—especially about tone, which in the opening half-hour slides between hipster whimsy and cartoonish archness, except when the monster is roaring and rumbling and feasting. The decayed pastel color palette, often-symmetrical compositions, lunging and tilting camera, and super wide-angle images situate “Dust Bunny” beneath an aesthetic umbrella that also covers Tim Burton; Wes Anderson (“The Royal Tenenbaums” in particular); early Coen brothers films; slapstick comedies by the Coens’ first cinematographer, Barry Sonnenfeld (“Men in Black,” “The Addams Family”); and the French storybook sagas of Pierre Jeunet and his sometime partner Marc Caro (“Delicatessen,” “City of Lost Children,” “Amelie”). Fuller owns that last influence in the closing credits, announcing “Dust Bunny” as “Un Film de Bryan Fuller.”

Incredibly, after these and other influences are whipped together in the filmmaker’s Hobart Mixer of a brain, the result is a stylish and confident debut feature. The first third of is too arch for its own good and is marred by janky CGI and compositing. The opening sequence depicting the birth of the creature seems to be trying to decide whether it wants to be realistic or cartoonish, and ends up stranded in between. “New York” at night has that too-rushed, superhero-blockbuster look. Human performers and material props fail to blend with digitally rendered backgrounds. Visual flourishes that should be gobsmackingly gorgeous, such as the fireworks exploding overhead in the Chinatown battle and 5B’s acrobatic feats, come across as cheap. But once the story settles inside the apartment building, “Dust Bunny” becomes more solid, in every sense.

The binding element turns out to be the disreputable but enthusiastic genre films that Fuller consumed as a young man in the ’80s and early ’90s—stuff like the original “Gremlins,” “Fright Night,” “Tremors,” and “House.” These were movies that looked like goofy grindhouse time-wasters in TV ads, but had solid acting and writing, stretched their meager budgets with panache, and managed to seem playful even when characters were being incinerated, dismembered, and devoured. Fuller never plumbs too deeply into the implications of what he shows us, or attempts a grand statement. It’s not that kind of movie.

But he does present extravagantly imagined sequences, inhabited by characters trading quotable lines. (When 5B interrupts one of the Weaver character’s anecdotes with “Let me stop you,” she slaps back with “There’s no stopping this train—it’s going all the way to the station.”) The story never goes quite where you anticipate. The final battle is brilliantly staged and edited (by Lisa Lassek), with homages to beloved man-versus-beast films, 1990s acrobatic action comedies, and supernatural thrillers. The creature effects are doled out sparingly at first, but when you finally get a good look at the dust bunny, it’s as funny as it is unnerving: a Muppet from hell. The closing shot is as good as closing shots get.

This isn’t a classic, but it’s good enough to make you think Fuller has a classic in him.