My eighth-grade teacher’s name was Mrs. Hughes. She always told us not to be a bump on a log if she saw that we weren’t using our energy to its full potential. I thought she’d coined the phrase until we read S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders as a class. It’s right there on the fourth page of the book: 14-year-old narrator and protagonist Ponyboy Curtis is cornered by a group of Socs and scared stiff: “I stood there like a bump on a log while they surrounded me,” he says, comparing himself to his Greaser friends who might have made a weapon of the trash around him.

It wasn’t just that phrase but also other terms she used that felt as though she was talking like the Greasers. She said “savvy” often. A few days before we began reading the book, Mrs. Hughes told us she used to be a rebel in high school, back in the ‘60s. In my mind, she became a corollary of Hinton herself. The day we began reading the book as a class, she recited the first line from memory: “When I stepped out into the bright sunlight from the darkness of the movie house, I had only two things on my mind: Paul Newman and a ride home.” My jaw dropped.

It’s not a complicated line, though it is important for Hinton’s story, which begins and ends with it. The line’s recitation, in hindsight, was nowhere near as objectively impressive as my high school English teacher’s recitation of the Hamlet soliloquy. But it was cool to me because it was the first time I saw that you could commit the words you loved to memory. Mrs. Hughes so obviously adored The Outsiders and got us excited about it, too. As we moved through the book section by section, she stoked our curiosity about the ending, maintained the interest of the least enthusiastic reader among us by promising we would watch the 1983 film when we completed the book, and had us fall as deeply in love with the characters and Hinton’s words as possible. We spent many days close-reading passages, thinking about why certain words appear and others don’t. She did all this not only by speaking the book’s language, but also by understanding our emotional one and reflecting it to us—this understanding came intuitively, from a lively memory.

Often, when we talk about teenagers, we otherize. “As soon as teenagers were invented, they were feared,” writes American journalist Derek Thompson, noting the cultural fear in the middle of the 20th century that the nascent group of “teen-agers” inspired with their loud social presence and financial power. When we talk about teenagers, we talk about them as though they were a different breed, as though we’ve forgotten that we’re talking about ourselves. Even Thompson is guilty of a slight othering: “The last 60 years have made teenagers separate. But are they really so different? Or are teens just like adults — but with less money, fewer responsibilities, and no mortgage?” Teens aren’t just like adults, they are a moment in adults’ lives.

Teens become this unknowable group about whose differences we wonder in the same way we wonder about a dolphin’s similarity to us. Teens are separate and legible only in reference to or comparison to adults, so seldom acknowledged in their own right as complex beings, as past versions of ourselves. Mrs. Hughes was able to get us excited about a book decades older than us because she didn’t otherize its subject matter, because she continued to see herself in its pages. And Hinton—her work continues to be read by kids across North America because she wrote from experience and memory.

Often, when we talk to teenagers, we tell them that one day what they are feeling will not matter as much, which is another way of saying they will forget they were teenagers. We tell them, in so many words, that they will grow to become alienated from their younger selves. Hinton and the films inspired by her writing, like Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Outsiders” and Christopher Cain’s “That Was Then… This Is Now,” refuse to forget. Rather, her worlds dig their heels into the nowness of being a teenager, at once burdened with power and rendered disenfranchised and powerless, something more visceral than representation: empathy without a desire to correct. Hinton’s touch is an allowance of and lingering in the big mayhem of teenage feeling, an acknowledgement of that cataclysmic moment before we come of age.

Teenagers have a distinct temporal emergence as a social group. Beginning with the Industrial Revolution and industrial capitalism, when people began moving to cities to be closer to the factories where they labored, many took their kids to work with them. Other kids found semi-skilled jobs, which they easily secured because kids were seen as cheap labor. There was as yet only a distinction between childhood and adulthood. Many children from the working class worked into the 1930s. Already, by the early 1900s, people, like photographer Lewis Hine, were working to raise awareness around the horrifying conditions under which children were made to work. Alongside various labor movements and workers’ reforms, which enforced labor standards, there were calls to end child labor. Liberal thinkers and artists, among them Hine and his photographs, spearheaded a societal moral objection to child labor. Widespread criticism and counter-movements meant that, by the mid-century, child labor was much more regulated and legislated against.

No longer able to work, the kids had to go somewhere, and so public education was made mandatory. “Between 1920 and 1936, the share of teenagers in high school more than doubled, from about 30 percent to more than 60 percent,” writes Thompson. As most groups do, kids in school developed their own culture—a language, etiquette, and value system. By the ‘50s, a period of great economic expansion for America, older teens and adults received higher wages, allowing the latter to pass more money to their kids. Younger people had more money and leisure time than ever before, and their spending power was recognized and tapped by the commercial industry. The world around teenagers began to mirror teens’ culture, giving them things to buy and consume that reaffirmed their unique being in space and time.

It wasn’t long before mainstream society began to see teenagers’ power—their social and financial capital—as a threat, as something nefarious. Teens became a problem. Thompson quotes a New York Times critic: “The abolition of child labor and the lengthening span of formal education have given us a huge leisure class of the young, with animal energies never absorbed by tasks of production.” The juvenile delinquent (JD) became a looming specter of social destruction. In 1953, J. Edgar Hoover warned of an increase in crime rates brought on by teens, and the JD became a “nationwide problem.”

It was within this anxious climate of the ‘50s that “Rebel Without A Cause” was released. Directed by Nicholas Ray, the film stars James Dean, Natalie Wood, and Sal Mineo, and follows Jim, a teenage boy, over the course of his first full day in a new town and high school. Jim, who has a troubled past (he is known for fighting anyone who calls him the emasculating term “chicken”), is determined to make good in his new home. Jim has an overbearing mother and resents his father for not standing up to her—in Jim’s eyes, his father is emasculated, too sensitive, too housewife-like. Wood’s Judy, meanwhile, has a father who isn’t sensitive enough; he has withdrawn his love from her as she matures and feels it is inappropriate to be affectionate with a young woman. Mineo’s Plato, too, has trouble with his parents, but in his case, they are totally absent. The film suggests that teens act out and are troublesome because adults haven’t done a good enough job raising them, but it focuses primarily on the havoc the kids wreak.

There is a certain sense in which “Rebel Without A Cause” considers the teenager from the outside as a puzzle to be solved. For its first twenty minutes, the film oscillates between Jim, Judy, and Plato as they move through the Juvenile Division of the police station. Officer Fremick takes a great interest in the three teens, spending a lot of time talking with each, trying to figure out the cause of each teen’s disturbance. With Judy, he understands that she wants her father to love her. In Plato, he sees a kid left with more freedom than he wants and not enough love, and in Jim, he sees a boy full of anger and frustration and words, but no outlet. Fremick takes a psychoanalytic approach to helping the kids, making an effort to understand them that would have been familiar to audiences, given its conversation with the pop-psychology craze in the mainstream.

The fearful mainstream culture worked hard to solve the problem of the youths, to make sense of their actions, to find causes for the effects of their roaring, “animal” energy. Fremick tries to fit Jim’s anger, Judy’s budding sexuality and desire for love, and Plato’s violence within a framework of logic and science, but in so doing, he loses sight of the kids, their desires, and the words carried by their anger; he loses sight of themselves. Dean, Wood, and Mineo certainly humanize their characters to beautiful effect, but the film still feels like it is about the failures of adults.

Lost within the rush of history and obsessive meaning making and reason finding, it wasn’t until the ‘60s that teenagers were saved by S. E. Hinton, their irrational emotionality, and an autonomy of feeling, given back to themselves. Finally, they were seen in themselves and allowed to exist for themselves.

During recess in grade eight, we traded trivia about the making of Coppola’s “The Outsiders” like it was Pokémon cards. Did you know a bunch of eighth graders got him to even make the film? I asked my friends. A school librarian named Jo Ellen Misakian wrote to Coppola, telling him about the love her seventh- and eighth-grade students had for Hinton’s book. “We are all so impressed with the book, The Outsiders by SE Hinton, that a petition has been circulated asking that it be made into a movie,” Misakian’s letter read. “We have chosen you to send it to.” Coppola recalls “children’s signatures written in different-coloured pens.”

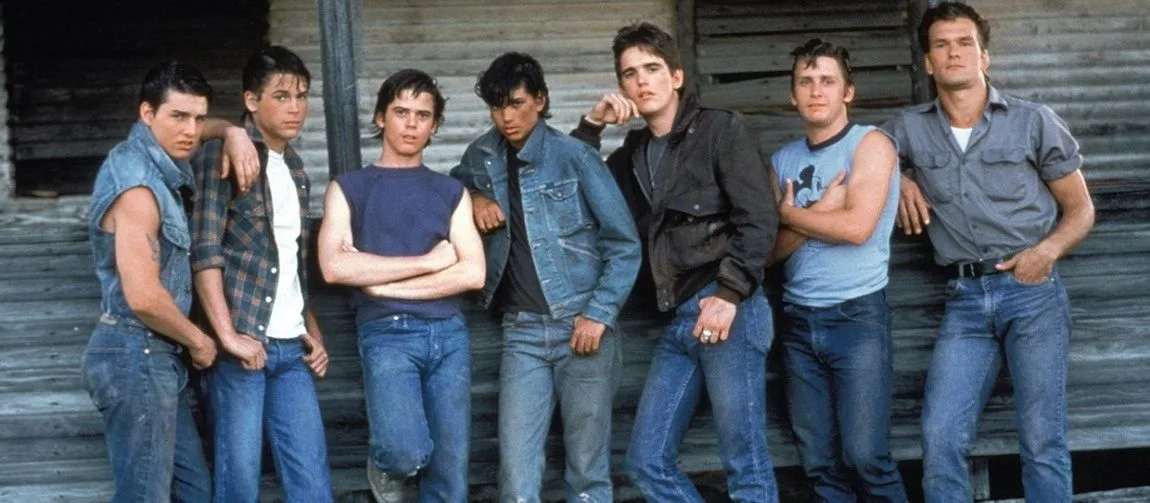

The novel was published in 1967, when Hinton was 18, but she began writing it when she was 15, after a friend of hers was severely beaten for being a Greaser. The film maps almost exactly onto the book and does so eloquently. In 1965, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, there was a violent rivalry between the Greasers and the Socs (or Socials). The former are poor kids who put too much grease in their hair, and the latter are rich kids allowed to get away with anything and everything. Socs often drive through the Greasers’ part of town looking for lone kids to jump. When Ponyboy (C. Thomas Howell) and Johnny (Ralph Macchio) get violently jumped by a handful of Socs, Johnny kills one of them, and the two boys go into hiding at the behest of Dally (Matt Dillon, his face as if carved by the hands of gods). The Soc kid’s murder brings on a reckoning for the two groups, and a rumble (a big fight) is scheduled to decide their fates: if the Greasers win, the Socs must leave them alone, and if the Socs win, then things go on as usual.

The story is many things, prime among them a consideration of wealth disparity and the treatment of poor kids in comparison to rich kids. Young Hinton does attempt to empathize with the rich through the character of Cherry Valance (Diane Lane), the girlfriend of the Soc Johnny kills. Ponyboy asks Cherry if she can see the sunset from her side of town, and realizes that they both admire the same sky. Everyone has it tough, no matter class, Cherry tells Ponyboy, but it’s a message that doesn’t sit too well with Ponyboy, who wonders until the end of the story at the unfairness of his lot compared to the Socs’.

The deck is stacked decidedly against Ponyboy and his friends. Ponyboy’s 20-year-old brother Darry (Patrick Swayze) takes care of him and Sodapop (Rob Lowe), the middle Curtis brother. Their parents are dead, and CPS threatens to separate the boys at any moment, at any misstep. Dally’s parents are uncaring of his existence; Dally could die in jail, and they wouldn’t bat an eye. And Johnny’s parents are never not fighting with each other or hitting Johnny; often, the boy sleeps on a dirty mattress in an abandoned lot because it’s better than going home. The Socs don’t have it nearly as tough as the Greasers, and Ponyboy, perhaps through a burgeoning class consciousness on Hinton’s part, feels this.

But what resonates most with kids, what resonated most with my eighth-grade class, wasn’t its critique of class so much as its bleeding heart. “Socs were always behind a wall of aloofness, careful not to let their real selves show through,” Ponyboy notes in the book. “[Y]ou don’t feel anything and we feel too violently,” he says to Cherry. The Greasers have “too much energy, too much feeling, with no way to blow it off,” the boy notes early on in the book. Too much “animal” energy, unchecked by societal mores. Energy like we felt at the time of our reading.

The Greasers fight hard and love hard. In the book, this is evident in the blood they make others shed and the blood they shed, in the tears they cry, in the hugs they are unabashed in giving to each other, in the words they say, and in the admiration they easily voice. All this is present in the film, too, and more. There is much to be said about touch and physicality in this film; the Greasers’ movement exudes communal joy and fearlessness. They love acrobatics, goofing around with each other, and they take immense pleasure in letting their energy flow from them to those around them through sport, an arm across another’s shoulder, or a back flip. These are young men who love without qualification or care for gender norms—time and again Ponyboy observes and remarks upon his brothers’ and friends’ beauty. It’s not sexual, but it can be if that’s how you want to read it; the relationship between Sodapop and Tom Cruise’s Steve is certainly sexual in the way that teenage friendships sometimes are. Johnny rhapsodizes about Dally’s gallantry. When Cherry tells Ponyboy that she would fall in love with Dally if she saw him again, Ponyboy understands; he sees the same qualities in Dally that Cherry does.

There seems to be no reserve among the Greasers, but rather honesty. All the feeling and energy is articulated as it arises in them; feelings of love and rage are honored, always, never rationalized away or suppressed or obfuscated in the way that the Socs have mastered. Ponyboy, Johnny, Dally, and the rest of them—despite how awful their material circumstances are, despite how hard they have to work to stay alive—are a beautiful lesson in feeling, in loving. We talk often about teenage hormones, how embarrassing and awkward they are, but “The Outsiders,” both film and book, is one of the very few works of art that doesn’t shy away from celebrating the earnestness of teenage feeling. Everything is urgent when we’re teens, and Hinton and the film understand this.

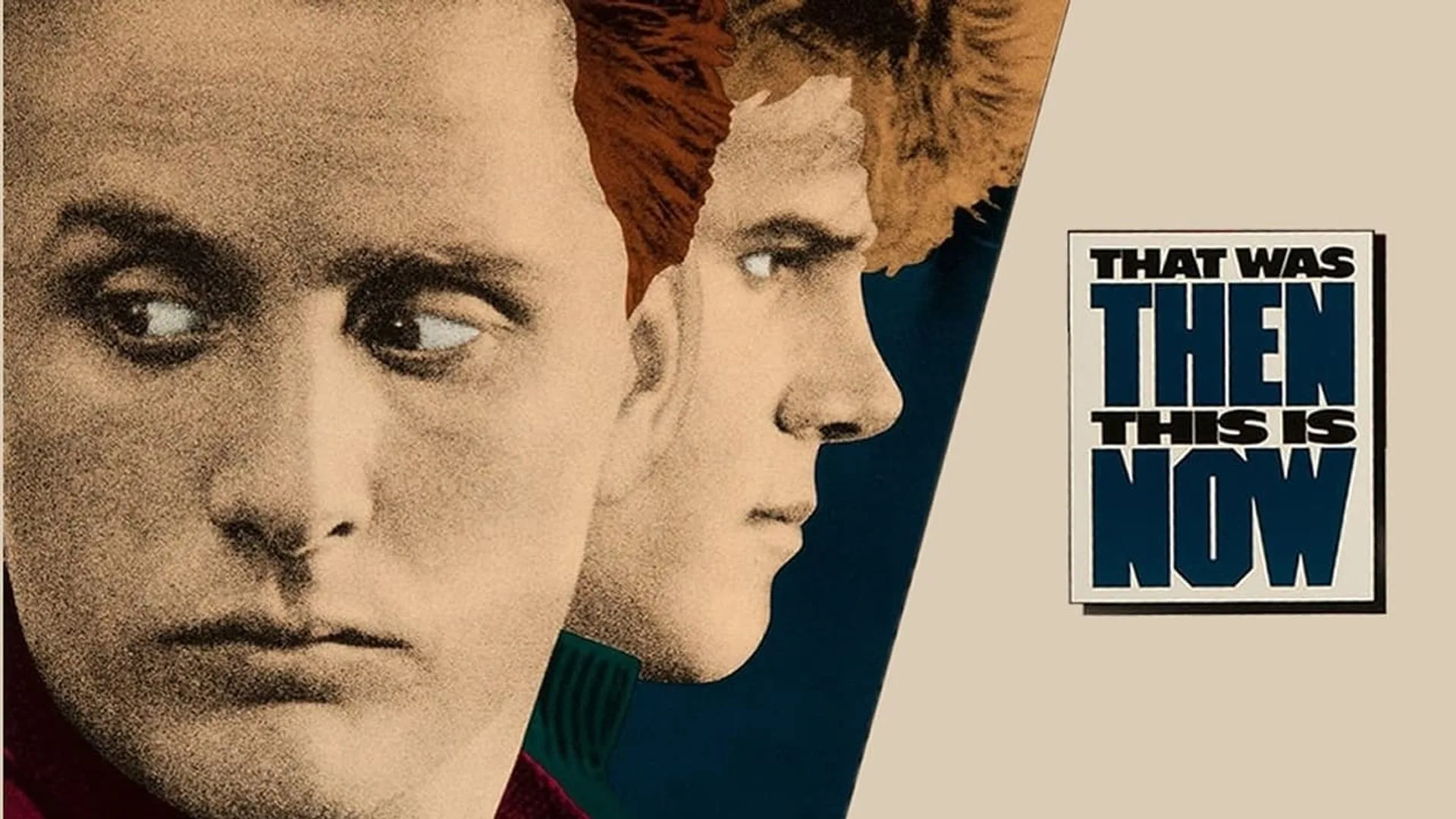

After “The Outsiders,” Hinton suffered a severe case of writer’s block, and it took her a while to pen “That Was Then… This Is Now,” which she published in 1971. Emilio Estevez, who plays Two-Bit with mesmerizing comedic grace in “The Outsiders,” penned the screenplay for the 1985 movie adaptation, “That Was Then… This Is Now,” and also starred in it as Mark, opposite Craig Sheffer’s Bryon, and Morgan Freeman’s Charlie. The story takes place two years after the events of “The Outsiders” (Ponyboy makes several appearances in the book), but focuses on Bryon and Mark’s friendship and how it unravels over time. The story is freighted with ancillary ideas about modernity, cultural attitudes toward hippies and drugs, and class consciousness (the Socs have started dressing like Greasers because looking poor is cool now). Hinton adds a simmering understanding of racial tension.

Sixteen-year-olds Bryon and Mark have been friends for as long as they can remember. When Mark’s parents killed each other in a domestic violence incident, Mark moved in with Bryon and his mom. The boys were reckless, as most of the other poor kids around them were. But as Bryon nears seventeen, he begins slowly growing out of his past ways, while Mark leans into them with a renewed ferocity, for fear that time will tear him away from the only family he has known and loved.

At one point in the book, Bryon’s girlfriend yells at her father for chiding her brother. “It’s not just a stage!” Cathy yells. “You can’t say, ‘This is just a stage,’ when it’s important to people what they’re feeling. Maybe he will outgrow it someday, but right now it’s important.” It’s an impactful encapsulation of the guiding idea behind much of Hinton’s work. Even as “That Was Then” is about the changes time wears on young people, it also doesn’t gloss over their feelings as time, as history, is happening to them. Much like “The Outsiders,” “That Was Then” articulates the yearnings and hurts both Bryon and Mark experience in the moment; it doesn’t trivialize their feelings, but rather sees them in their bigness, because they are big when they are felt, they are big right now.

In general, many teen movies are cautionary tales or raunchy comedies. Most films treat teens as just smaller adults, giving them problems that few kids in real life are saddled with; most films make sense of teens in reference to adults. Few films respect a teen’s feelings without also ridiculing them. A film like Kelly Fremon Craig’s “The Edge of Seventeen” is a rare gem for the way it wears a Hinton-esque gaze on its protagonist’s sadnesses, frustrations, and joys. The protagonist is shown to blunder or rage with hubris in the way that kids do, because the film understands that she is a kid, much like how “The Outsiders” understands that Ponyboy and Johnny are kids, and so doesn’t back down from showing them huddled together and crying after running away from home.

At the heart of Hinton’s stories about teens is the anger, the love, all those intense feelings that we often forget about when we grow up, maybe when the hormones stabilize, maybe because of the rush of time, the arrival of an age that we’re told matters more than the right-now messy thrum of a young life. The complexity and hectic immediacy of youth—all this small stuff that feels so important because it is important, because it is all a young person knows—are preserved and therefore honored by Hinton in her written word and in the films based on it. Mrs. Hughes seemed to come alive with these teenage feelings alongside us, evident in her excitement and in her recitation of the little words that begin “The Outsiders”. For a moment, Mrs. Hughes became just like us; for a moment, we, students and teacher, were on equal ground.

Time and again in Cain’s “That Was Then,” Bryon is told by the adults around him that everything he is feeling, what he’s going through, will not matter when he is an adult. He is told this as though it were something to look forward to. But the film, Cain and Estevez, knows better. The most poignant moment in “That Was Then… This Is Now” takes place a bit more than halfway through the film. Both Bryon and Mark are drunk; they have just pulled a childish prank on a girl they don’t like. Bryon asks Mark about his parents, why they killed each other. Mark sits by the window, and the deft camera and lightwork make the rainwater streaming down the windowpane look like tears are running down his face.

Mark says they were arguing over him, that his father doubted he was his real son, and that his mother finally told him Mark isn’t. “And they started screaming back and forth, and I just heard this sound like a couple of firecrackers,” Mark says. “That’s just what it sounded like, firecrackers. And then I thought to myself, I can go live with Bryon and his mom,” Mark says. “I was nine years old.” He says he got sick of them fighting all the time, that he was beaten a lot. “I remember thinking, man, this will save me the trouble of shooting them myself. I don’t like anybody hurting me.” It’s one of the film’s most jarring and frightening moments because of its honesty. I love this scene because it does something more trenchant than exposition or backstory or adding tension; it serves as a reminder of Mark’s kid-ness. The words Mark uses, many of them are Estevez’s own addition to Hinton’s, and together they depict the illogical wishful thinking any child in a dangerous situation partakes of.

“The Outsiders” and “That Was Then” never forget that they depict kids, even when the kids are given responsibilities or trials no kid should have to bear. Dally, as he playacts as a tough guy, still wishes his parents cared about him, which is why he loves Johnny so intensely. Darry, though he is 20 years old, is deathly afraid of losing his little brother, like he lost his parents, and shy, sweet Ponyboy cries because he is afraid and feels guilty about harboring bad thoughts about Darry.

Never do the films take pains to place blame for the teens’ living conditions on parents in an effort to solve the boys, to psychoanalyze them, because to do so would be to control the kids, to decenter the kids, to rationalize their existence away in the way a patronizing, paternalistic gaze might, or to turn them cold like the Socs, in the way a gaze that rationalizes that kids are adults in waiting would. The Socs are cold and aloof because their world is the world of adults, and seeing kids as smaller adults is to see them only in reference to adulthood. These stories remember their characters’ kid-ness and honour it; they remember they’re about how these kids feel in their environments right now. In Hinton’s worlds, the kids feel free, for better or worse. The Greasers aren’t responsible for the conditions under which they live, but they don’t spend much time trying to best them, either. Like most young people, they live their lives the best they know how–and this living is what Hinton limns.

At a time when much of society looked down on a group of kids fearfully, denied them their humanity, and ignored their pains and happinesses, Hinton gave this much-maligned group a voice and an image. Even now, we foist adulthood onto young people, hate teenagers for their loudness and silly slang, want them to grow up already, even as we see and exploit them for their power as consumers and buyers, forgetting all the while that we used to be just like that. We used to be just that. But Hinton remembers. She, and the films inspired by her work, taught me how beautiful unabashed love is, how it survives despite hurts, and how it is worthwhile right now, even if we might forget its vibrancy tomorrow. Right now, all these messy and loud and big feelings are important.