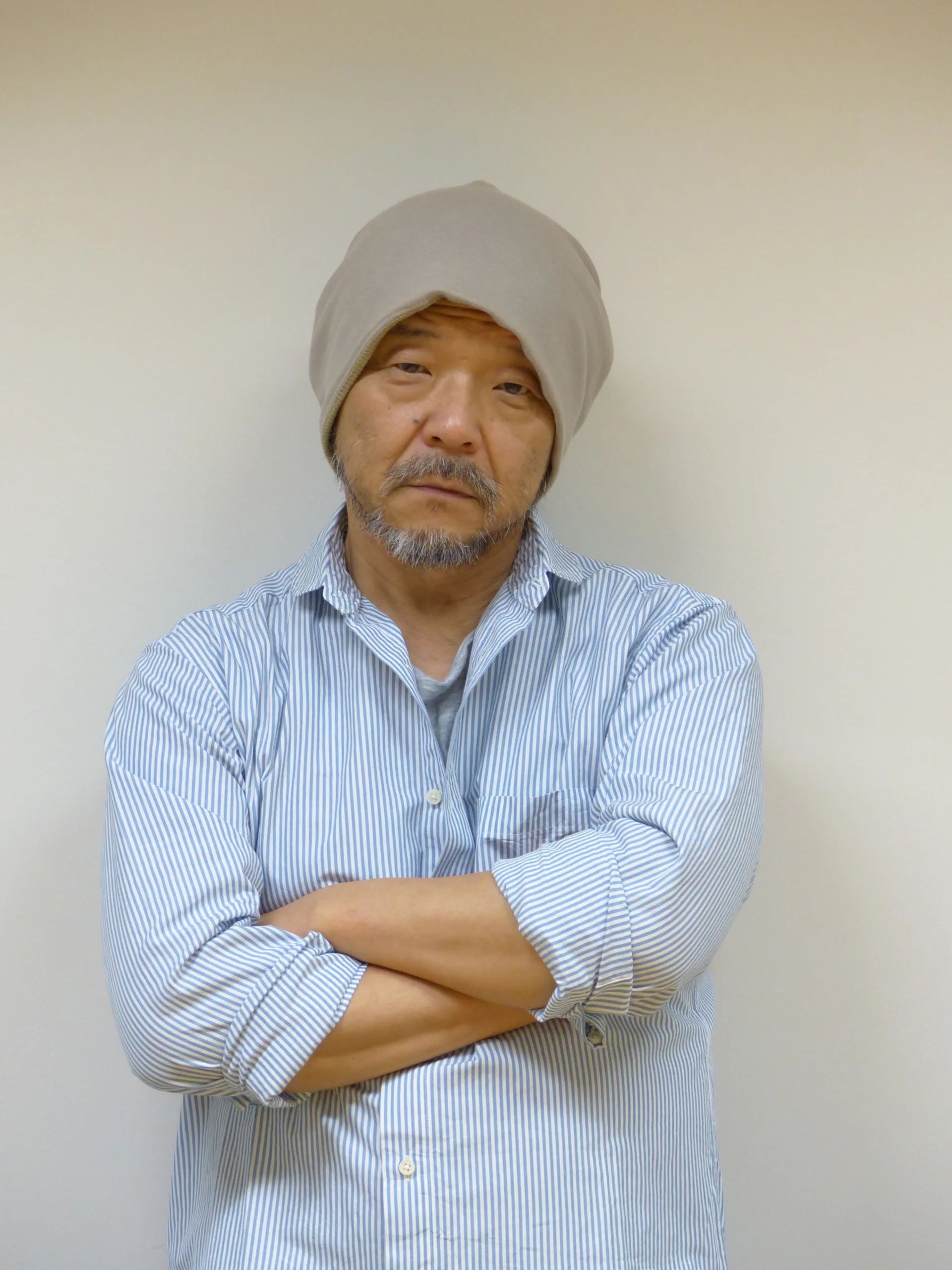

In a career retrospective talk at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival, Mamoru Oshii spoke, if not regretfully, mournfully about “Angel’s Egg.” The legendary Japanese writer and director—who secured his place in animation history with “Ghost in the Shell”—said that his dreamlike, allegorical 1985 OVA film nearly killed his career: “After that, nobody gave me jobs for three years,” he said. He went on to describe the film as his “poor daughter,” the one who stayed home while his other films went out into the world and found success.

To extend the metaphor, now she’s all grown up and moving out of the house. “Angel’s Egg” was restored in 4k earlier this year, and since then has enjoyed a global run that included a premiere at Cannes in May and a homecoming at the Tokyo International Film Festival in early November. It’s played at a mix of festivals, from modest and genre-specific to high-profile gala events; this reflects the shifting status of Japanese anime on the global cinema scene, as it evolves from a niche interest into a global box-office phenomenon and a genre worthy of serious critical consideration.

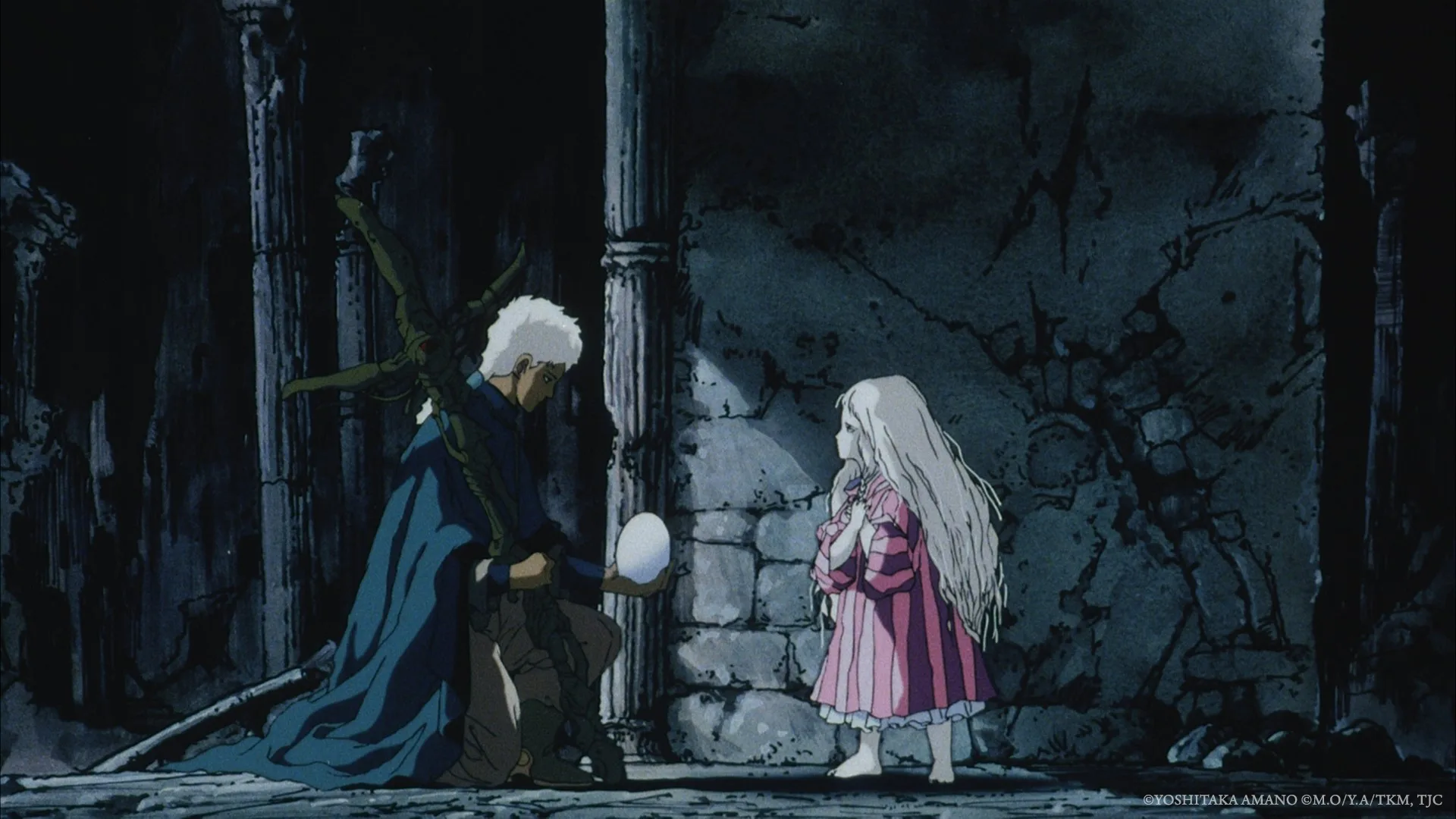

“Angel’s Egg” is at the forefront of the latter, a cryptic, symbolically loaded work of art that’s better felt than intellectually understood. It combines Christian imagery with delicate hand-drawn animation and a story that’s stripped down to its most essential elements. There’s a girl, devoted to caring for the mysterious egg she carries with her at all times; a boy, carrying a gun in the shape of a cross, who joins her in her lonely vigil; an empty, bombed-out city, a heavenly host frozen in stone, and a floating eye covered in black spikes that may or may not be God.

We spoke to Oshii over email shortly after “Angel’s Egg” screened in Tokyo, in advance of the film’s theatrical debut in North America this week, November 19th. And his answers were as intriguing and enigmatic as the film itself.

You’ve talked about the influence movies have had on your work—what ideas or philosophies drive you as a filmmaker, or just as a human being?

It’s not an ideology or a religious belief, but rather a kind of religious passion—perhaps something closer to a “fetish” or “libido.” It’s extremely difficult to explain.

What was the motivation behind incorporating Christian imagery like the cross and the “heavenly host” into “Angel’s Egg”?

I was never a Christian, but I was fascinated by the Bible and read it passionately when I was young. I’m certain that experience laid the foundation for my way of expressing metaphors.

What references or influences did you use when you were designing the backgrounds in “Angel’s Egg”—specifically, the abandoned city?

I’ve been drawn to abandoned cities since childhood, so I’ve definitely been inspired by photo books of that kind. I’m also attracted to Western architecture, which I think works beautifully in animation.

The characters and the settings in “Angel’s Egg” are abstract; they contain elements of our world but are detached from our reality. How did this elemental quality affect the creation of the film: the design, the storytelling style, and so on?

My goal was to convey the concept through the film while minimizing the focus on the characters and the story. The characters, as well as the story itself, are merely symbols—materials for visualizing metaphors. When I made this film, I believed it was possible to express that idea through cinema.

Is your personal interpretation of “Angel’s Egg”—or any of your work—relevant to us in the audience?

A “movie” is an imperfect form of expression in many ways—and I think that’s its greatest charm. I feel a film truly fulfills its purpose only when it’s being discussed and talked about.

Locations and showtimes are available on the GKIDS website.