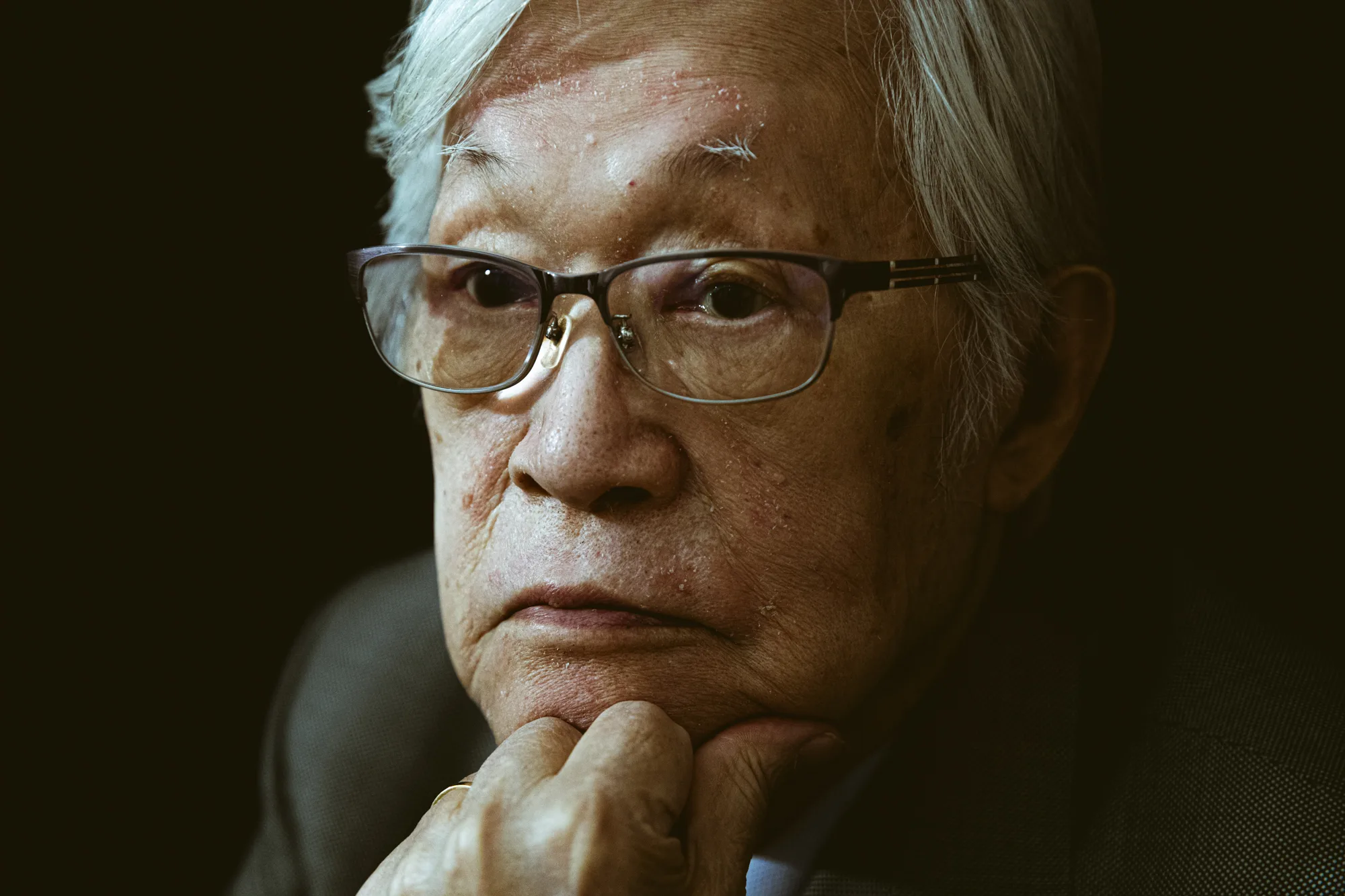

Before I sat down to watch the documentary about him, I had only heard the name Sato Tadao once. It was in an article by Roger Ebert, a piece about Yasujiro Ozu’s rise in popularity in the West, in which Ebert referred to Tadao as a “veteran Japanese critic” whom he had met while on a trip to Tokyo. Both Tadao and Ebert were great admirers of Ozu’s, and in the article, Ebert lays out a series of the director’s stylistic signatures, crediting them to his Japanese counterpart’s writings on the subject.

Directed by Terasaki Mizuho, “Journey into Sato Tadao” is a biographical portrait that makes the case for Tadao as one of Japan’s most important film critics. The film is loosely structured around Terasaki’s journey to the state of Kerala in southern India, where she seeks out the people behind Sato’s “actual” favorite film, “Kumatty” (1979), by director G. Aravindan. The quotation marks originate from a sequence early on in the doc, in which Sato—who died in 2022, but appears in footage Terasaki shot before his passing—says that he has two answers ready for when someone asks him his favorite film: A respectable one, and a real one. (Ironically, the Roger Ebert piece that led me to Sato also opens with an anecdote about recommendations.)

Later in the film. Terasaki and her crew also travel to South Korea to interview Sato’s friends and colleagues there, part of a larger discussion about film critics as cultural ambassadors who can make real, material changes in filmmakers’ lives by advocating for them abroad. (I’d argue that it’s one of the nobler functions of film criticism as a profession, and something I’d ideally hope to accomplish by writing about the films I see here in Tokyo.) For Sato, this relationship went two ways: not only did he write about Japanese films for foreign readers like Roger Ebert, but he also played a big role in popularizing Indian and South Korean cinema in Japan.

Sato speaks warmly of his friends across Asia in “Journey into Sato Tadao.” Terasaki believes that these relationships must have been a relief to the writer, who, despite his working-class background, rose to become a member of Japan’s social elite. But he was never comfortable there, and maintained throughout his life that cinema should be for the people. “Everybody looked up to him. He was a scholar. People used honorifics to talk to him” in Japan, Terasaki says. “But I got the impression that the people in Korea and India did not have that kind of a distance between themselves and him. I think that made him happy,” she says.

Although Sato’s international impact serves as a framing device for the documentary, its heart is in his relationship with his wife, Hisako. “Journey into Sato Tadao” paints Tadao and Hisako’s relationship as a partnership of true equals, in which Hisako, who was already successful in her own right when she met her future husband, was a strong advocate for (and presence in) his work. In 1973, they cofounded the film journal “Eigashi Kenkyu,” which is still active today. “Their love affair was very colorful,” Terasaki says.

Here was another parallel. Since Roger’s passing in 2013, Chaz Ebert—who also had a successful law career before meeting Roger—has been the steward of his legacy, and is the publisher of the website you’re reading right now. And the similarities didn’t stop there: Sato also published books on film and film history, many of which are seminal texts to young Japanese film lovers. (He was more prolific than Ebert, however, publishing more than 150 books on various subjects in his lifetime.) And, like Ebert, Sato taught film as well as writing about it.

Back in the ‘00s, Terasaki was a student in one of Sato’s film classes at the Japan Academy of Moving Images, where her initial impression was that “he [knew] anything and everything about Japanese films. And whenever he talked about a film, his face lit up like a little boy’s. It showed how much he loved movies. But otherwise, he was not easy to approach.” Years later, Terasaki was working as a documentary producer when she got an offer to direct a doc about her former teacher, the one she found so intimidating back in film school.

“At the beginning, I couldn’t really figure out his character,” she says. “But then Sato’s niece “gave me a diary that he wrote when he was around 25. And in that diary, he mentioned his anxiety about the future, and his dreams for what he wanted to do [with his life]. Reading that, I realized that this young Mr. Sato was very accessible, and so the psychological gap between him and I became smaller and I was able to relate to him more.”

Passages from Sato’s diaries, as well as his books, are quoted throughout “Journey Into Sato Tadao.” In choosing these passages, Terasaki says she prioritized writings in which Sato was processing his experiences in the moment, whether his feelings about the devastation of WWII or his reflections after seeing a new favorite film for the first time. The passage that resonated with me the most is about writing: “When I write it down, that’s when I start to see what I’m thinking. When I’m not writing, I don’t know what I’m thinking,” Terasaki quotes Sato as saying.

Although she’s not a critic herself—in typically modest Japanese fashion, she says she keeps a diary of films she’s watched, but doesn’t share it with anyone—the more we talked, the more I realized Terasaki and I had in common. Not only are we women from the same generation working on projects about famous older male critics who inspired us early in our careers, but we’re also both devoted cinephiles. Her favorite film is “Pigs and Battleships” by Imamura Shohei (incidentally, also the founder of the school where Sato eventually taught), and he hopes to film something as good as its ending someday. She’s been attending the Tokyo International Film Festival for years, although this is the first time she has a film in the festival.

Cinephile culture in Japan is strong, but insular, Terasaki says. “We have a wonderful library at the National Film Archive. And so these films are being preserved, but we’re not very good at using the archive to its fullest and showing them to public audiences. They do have screenings, but only film fans attend, not the general public. So I hope that there will be chances where “ordinary people” will have the chance to see these old Japanese films and become more interested in Japanese film history, because it is a fascinating subject.”

When I explain to her Roger Ebert’s famous quote about film as an “empathy machine,” she brings up another quote from her former film professor in response. In his book “Can You Love the World Through Movies?,” Sato “left the words that film is like a greeting, meaning that you can show the world what kind of a country you are, or what kind of person, or culture, through films. Then you’re able to learn about that country, or learn to like that country, through its films,” she says.

At the end of our interview, the translator told me that Terasaki had a question for me as well: Was there a documentary about Roger Ebert? I said, yes, it’s called “Life Itself.” “Ah! I watched that as research for my film,” Terasaki replied. Turns out she’s a Steve James fan, too.