Director Michelle Garza Cervera’s “The Hand that Rocks the Cradle” is one of the rare remakes that justifies its existence. It has the narrative bones of late director Curtis Hanson’s 1992 thriller, focused on the escalating conflict between a furtive mother and the unstable nanny she’s hired–but it’s cloaked in anxieties that make it feel achingly modern. Even if you don’t take your horror elevated, there’s plenty on the surface that makes this a story worth re-haunting you.

One aspect that Cervera doubles down on in this version is the excess and isolation of suburban life, which doesn’t necessarily keep evil away but rather invites it to fester. Taking on the nanny role made famous by Rebecca De Mornay’s unhinged performance, Maika Monroe stars as Polly Murphy, who’s been hired by married couple Caitlyn (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) and Miguel (Raúl Castillo) to watch after their children Emma (Mileiah Vega) and newly born Josie (Lola Contreras and Nora Contreras). Caitlyn helped Polly with a landlord dispute in the past, and soon enlists her for her services after a chance encounter with her at a farmer’s market.

At first, it’s a dream set-up: Polly is naturally gifted with kids, refusing to talk down to them and meeting their curiosities with respect. It also helps that the couple feels they’re doing the down-on-their-luck girl a favor: in the first scene, where Polly drives up to the Morales’ house, her beaten-up car, duct tape barely keeping the right mirror up, stands in stark contrast with the wealthier family’s automated garage gate and pristine new vehicle. This won’t be the first time Cervera’s film comments on the ways wealthy people use their money to shield themselves from what they would rather keep hidden.

Things then begin to unravel as quickly as they came together: Polly feeds Josie formula after Caitlyn explicitly tells her not to, and one of Caitlyn’s co-workers, Stewart (Martin Starr), discovers that Polly may not be telling the full truth about her work experience. Miguel is quick to suggest that Caitlyn’s worries around Polly are born from a severe bout of postpartum depression, which makes Caitlyn second-guess whether she’s suffering from jealousy or paranoia.

Much of the suspense around the original film revolved around a lack of proper vetting. There was no social media for Annabella Sciorra’s Claire to vet De Mornay’s Mrs. Mott, making the reveal of Mott’s twisted motivations more understandable. An ambience of trust characterized ‘90s suburban culture, and the film’s terror came from how that trust was exploited. The world is much more cautious now, but Cervera seems to suggest that even with the proper tools at our disposal, that doesn’t make us more intimate with those around us when we’re flooded with more information about people than ever. We see this underscored in Polly, who is hired so expediently by the Morales (about a half hour in). I’m tempted to critique the rapidity of this narrative development, but this shorthand speaks to how ready we are to trust someone if we think we can get something out of them.

Indeed, the film’s crescendoing narrative can also speak to this mindset. The moment we meet Polly, something is disquieting about her; Monroe plays her with brittle instability, but we can’t help but sympathize in some part with how Caitlyn will ignore some of Polly’s more unsettling tendencies. Polly’s usefulness outweighs her peculiarities; the film speaks to how we’ll often explain away danger for the sake of utility.

Monroe is no stranger to being a scream queen, and it’s a wicked treat to see her instead take on the role of the tormentor. Her Polly is an empty vessel motivated by nothing more than strange fixations and a sprinkle of vengeance. Monroe’s eyes and face hold moroseness and despondency well, and it’s terrifying to see her gaze through an antagonist’s lens. She’s a reminder of the inevitability of comeuppance, her quest to dismantle Caitlyn’s life rooted in righteous retribution. There has to be recompense for wrongdoing, and no number of automated garage doors, silk robes, and fancy refrigerators can protect the guilty from getting their due.

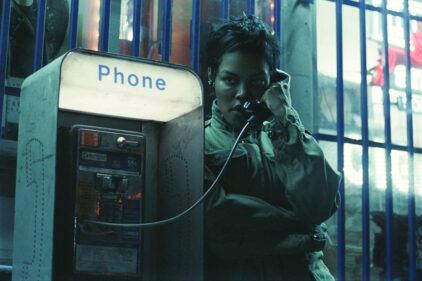

Equally holding her own is Winstead; Her Caitlyn laces regret in every quotidian act, whether she’s breastfeeding, on the phone, or cutting up vegetables. She clearly harbors a secret that makes her react to Polly’s transgressions and presence in such a visceral way. It’s a reminder that the shame we hold takes a toll not just on our souls but on our bodies. Caitlyn’s a soul looking for absolution, finding refuge, and feeling guilty for the life she’s constructed for herself, and Winstead tenderly captures the straddling of those emotions.

Scoring the war between these two is composer Ariel Marx, whose nightmarish and stressful songs feel like they’re being sung by an entity that’s out of breath in its struggle to break free from the confines of the film itself. Marx’s credits involve projects like “Shiva Baby” and “Sanctuary,” so she’s in a familiar, tense register here. Some of the film’s best moments occur when her work overlays scenes of domestic tranquility, creating a dissonance that highlights the latent violence about to befall the characters.

The title is cribbed from the poem of the same name by William Ross Wallace. In the poem, Wallace writes:

“Women, how divine your mission / Here upon our natal sod / All true trophies of the ages / Are from mother love imperaled.”

Mothering is a divine act, yet it’s a far cry from how we perceive and receive that role in the modern day. Cerveza has found a way to take an old story and comment on something new without fundamentally altering the source material. In this act of creation, she’s revealed the malleability of the text she’s working with and unlocked its storytelling potential.

It’s not an easy feat, and it makes me curious how another filmmaker, inspired by her work, might make another version of this story in thirty-plus years. So long as mothers continue to live in a world that doesn’t value their work, stories like “The Hand that Rocks the Cradle” will be prescient necessities.