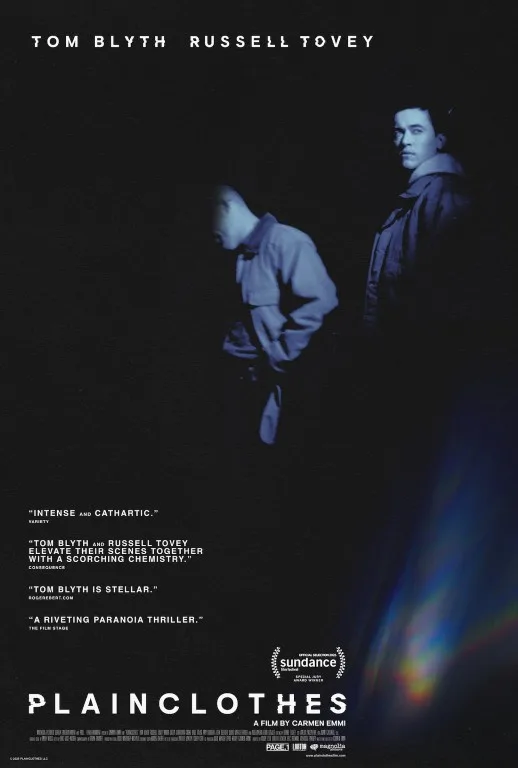

The ornate embellishments of an old movie palace bear witness to the encounter between two men testing the waters of desire. Hidden from the world’s judgment, at least for an instant, their flirtatious exchange provides needed reprise from the audiovisual whirlwind that is “Plainclothes,” writer-director Carmen Emmi’s debut feature set in the 1990s. That moment of tranquility for the audience, where the would-be lovers cautiously open up, reflects how Lucas (Tom Blyth), the younger of the two, feels in this scene: understood.

For most of the rest of this conflicted identity drama, Emmi and editor Erik Vogt-Nilsen construct fast-paced montages mixing formats (low-fi video footage and pristine digitally shot images) that mimic the turmoil inside Lucas’ mind as a closeted gay man. These deliberately choppy collages feature shots of his parents, his ex-girlfriend, his work colleagues, and even childhood memories, all rushing vertiginously through him, as manifestations of anxiety because he fears being outed and ostracized. Initially, the kinetic visual vitality of “Plainclothes” plunges one effectively into Lucas’ inner ordeal, but for as much as the form evokes how the character experiences the narrative, the relentless and repetitive fragmentation coated in in-your-face music overwhelms. And even if that feeling is the desired reaction, one wishes for a bit more discernment in its implementation.

Fueling his mental exhaustion is the fact that Lucas works as an undercover police officer involved in an operation to apprehend homosexual men cruising in public restrooms. With nods and stares, Lucas baits the targets, and once they expose themselves, another officer walks in to arrest them. It’s clear from his exasperation during these meetings that Lucas sees himself in the guys he’s helping put behind bars. The knowledge that their lives might be ruined further internalizes that he must remain simmering in his anguish. And then, on a routine day carrying out this police sting at a mall (an accurately ‘90s detail), Lucas meets Andrew (Russell Tovey), a quaint man, maybe a decade older than him, whose appearance screams ‘suburban married man with children.’ There’s an incandescent spark between them.

For Andrew, their subsequent rendezvous will remind him of what could’ve been if he could live openly, and for Lucas, they’ll act as a wakeup call of what could still be for him if he dares to be free. Emmi interlaces scenes taking place in the months after Lucas’ father passes and a New Year’s Eve party at his mother’s home with the entire family in attendance. Blyth, a British actor best known for his role in “The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes,” plays Lucas first as a boyishly handsome young man experimenting with sexuality, and later as a grizzled, mustachioed version of the same person but tormented by what he can’t say out loud. In both segments, Blyth’s face communicates a quiet desperation, his eyes pleading for an answer to his plight. It’s a riveting, soul-bearing performance of brewing frustration that becomes the centerpiece of the film, and anchors to a real bleeding heart, even as the more expressionistic touches take over.

Emmi’s construction of Lucas as a character, from the anecdotal information he divulges in conversations, points to a young man who doesn’t come from trauma or dysfunction, at least not in the way that homophobes might use to pathologize a person’s sexual orientation. Lucas had a close, loving relationship with an emotionally intelligent father. His grandfather was present in his life and even inspired him to enter law enforcement. And yet, Lucas loves who he loves, despite having these positive, heterosexual male role models around him and presenting as a traditionally masculine individual.

Written to hammer in these erroneous notions on the influence that a person’s upbringing has on their orientation, the most toxic presence in Lucas’ life is his obnoxious uncle Paul (Gabe Fazio), a homophobe who prefers to date women decades younger than him. In a heated tête-à-tête during the party after a supposed revelation stirs the household, Paul claims that the mere fact that he is not a homosexual makes him a more valuable man, despite his violent outbursts and his tendency to take advantage of others while not taking responsibility for his actions. Fazio embodies him with a recognizable and successfully unlikable arrogance. Men like Paul with such a retrograde mentality still abound today.

Paul’s bigoted virulence contrasts with Andrew’s calming resignation. A tenderly magnetic Tovey looks at Blyth’s Lucas with a singular mix of compassion, wisdom, and lust. He understands the young man’s fear of losing his loved ones because he’s risking the same, and yet the tantalizing attraction they feel for each other wins over their hesitation. Though some elements read forcedly wedged in for thematic potency, “Plainclothes” feels seductively alive when Lucas and Andrew are alone together—either under the warm lights of the movie theater, where their shadows betray them, or as their hands touch the other’s body inside a lonely greenhouse. It’s only there that they can breathe unburdened.