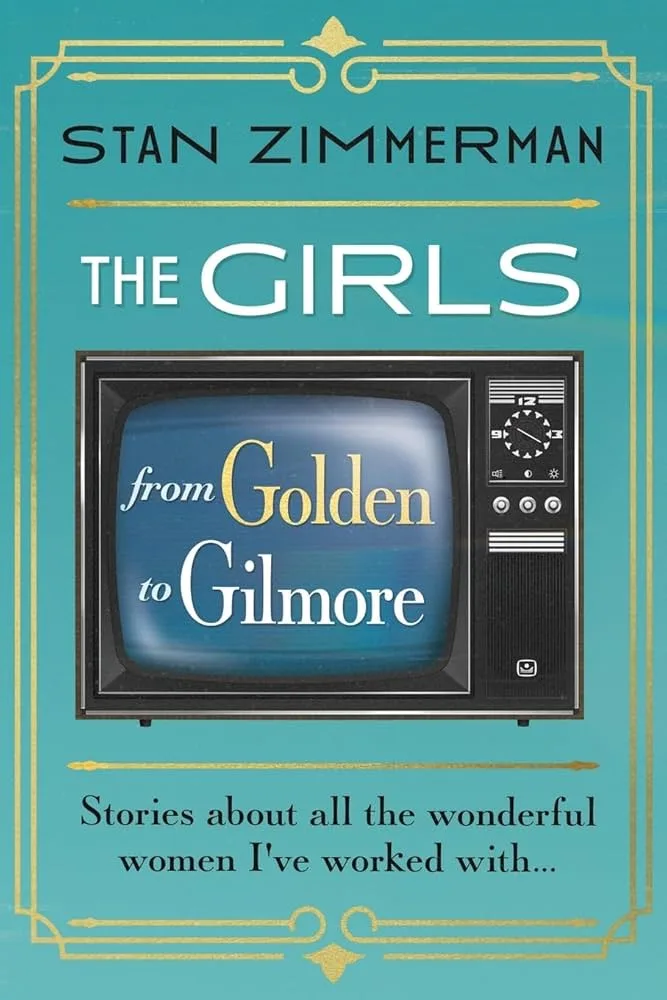

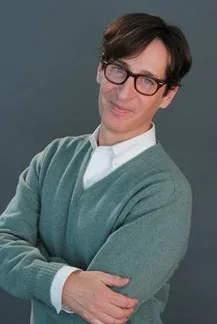

Stan Zimmerman is an actor, director, and writer whose television career included writing for three beloved female-led series, “The Golden Girls,” “Roseanne,” and “The Gilmore Girls.” His memoir, The Girls: From Golden to Gilmore, tells the story of growing up as a theater kid from the suburbs of Detroit, attending college at NYU, where he met Jim Berg, who became his writing partner, and his adventures in Hollywood. When we spoke, he was in New York, appearing in the play he wrote, Right Before I Go, inspired by the suicide of one of his closest friends. The rotating cast included Hill Harper, Wendie Malick, Peppermint, and Patrick Page, and Hill Harper.

In an interview with RogerEbert.com, he explains why he gravitates to stories about women, how to write with a partner, and which show changed the way he thought about writing.

In your book, you say that the question you get asked most often is how you are so gifted at writing for women, so let’s start there.

I think I have an ear for writing for women because I have a very vocal grandmother, mother, and sister. I was a young actor. I started officially at the age of seven and a half. And one of my first teachers said, “Just listen to other people and observe and watch people. Go to a mall, watch people.”

Well, I went to malls, I went to my living room, I went to my dining room table, and there was all this very loud, provocative discussion. And I just like the way they talk. My best friends were always women. And they, I think, are raised more being in touch with emotions and feelings, whereas when I was growing up, boys were taught to buck up, you know, be the tough one. They weren’t really given permission to have all the feelings. Always had the feelings and was a very, very sensitive child, and also a Libra. I always cared about other people. And so I think that’s why I was not only attracted to having best friends that were female, but also wanting to put into words and express what I would hear from them.

That makes sense, but I cannot imagine three more different kinds of women than the Golden Girls, Roseanne, and the Rory and Lorelai Gilmore. The tone, the tempo, the subject matter, and the personalities are very different. What did you say in the book about the number of pages in a “Gilmore Girls” script?

It’s 60 normally for a one-hour show, a minute per page, versus 90 for “The Gilmore Girls.”

Again, it goes back to listening to other people. In this culture, people don’t often listen. They stand in their corners and kind of yell at each other. And miss the mark of, if you could listen, then you can respond. We talk about that in acting as well, especially with improv. You can’t respond until you really hear what the person’s saying, then you say something back, then they say something back, and that’s beautiful writing.

I loved all the different styles. I loved “Roseanne,” the rhythm of that show. It wasn’t the same as I noticed in other sitcoms. It was closer to Norman Lear’s shows that talked about social issues. They are very funny shows, but not afraid of issues and getting deep, and maybe not playing for as many laughs.

In 2015, I was sent to Moscow to help them develop a Russian “Roseanne” show. The Russians only knew “Everybody Loves Raymond,” “Married with Children,” or “Golden Girls.” So with a show like “Roseanne,” they were like, “Why are there not more laughs?” And I had to explain to them that it was more like real life. There were a lot of laughs, but it wasn’t a farce where you had to have one per page. That is how it was taught to us in “Golden Girls,” which, for me, was really like sitcom writing 101. You could not have better teachers than those great writers and great pilot scripts by Susan Harris, but also those four actresses.

In the early part of your book, you say that you had an attitude. What was the attitude?

I took everything very seriously, and that started when I was in high school. When I got into sitcoms, having years of theater training and having attended NYU and earned my degree in drama, I wanted to delve into characters and understand why they were acting that way.

There were a lot of straight white guys who just wanted to go home, or they just wanted to talk about the game or something else. They didn’t really care about the underpinnings of the characters. And I found on a lot of TV shows, especially the female characters, their descriptions would be like “mid-20s pretty.” And I would raise my hand and go, “Um, can we give them one other characteristic? I mean, is that all she is?” I don’t think a lot of writers at that time wanted to hear that. And I looked like I was 15 years old, so they were having none of it.

I had to learn how to act on a staff as a writer in a group. I had to learn that they’re paying for your opinion. You give it, and then you walk away. You don’t have to hold so tight to it. They want to know what’s in your head and your heart. And then if they don’t want to use it, that’s their prerogative, right? They’re the showrunners. I’m here to offer a different perspective. And once I figured that out, it made everything so much easier, going to work and not taking it all so seriously.

With that in mind, what is it like to work for decades with the same writing partner?

Luckily, with Jim Berg, we met at NYU, and we just had this instant chemistry. And right away, we created this partnership when we didn’t even really know what a partnership was. We already decided, in college, what the billing would be. Our company name would be Zimmerman Berg, but our billing would be James Berg and Stan Zimmerman. And then we came up with this idea that if we worked all week together, we would take weekends off and not talk to each other, so that on Monday, we would come fresh with ideas. And we stuck with that until you get a job, where sometimes it does bleed into the weekend. We figured out ways to deal with disagreements sometimes. Because sometimes, as writing teams, you can have a fight over whether it’s “an” or if it needs a “the?” And so we came up with a method where we say, “What percentage do you really want to fight for this?”

Also, as in a marriage, don’t ever leave. Don’t go. Only a few times where we just have to say, “I just have to go in the other room for just a moment.” Very few times. We just learn to negotiate. But we see so similarly, and I’ve been so lucky to have such a long career with him. And we’re still going. We wrote a Lifetime Christmas movie with a female cast, “A Diva’s Christmas,” two years ago.

We were just commissioned to write a sequel to our “Silver Foxes” play with Dallas’s Uptown Players. So that’s due any minute. We will premiere a new musical that we wrote called “Long Beach Blanket Bingo” on the eastern shore of Virginia.

You and Jim have also spent time fixing other people’s scripts, another way of getting into somebody else’s voice. What is the mechanism for approaching something like that?

You can have a whole career rewriting other people’s scripts. We were brought in when Betty Thomas was directing “The Brady Bunch Movie.” Television is writer and producer-driven, but a film is really director-driven. The director is hiring us, so we begin with “What do you feel you’re missing from this script?”

We felt like The Brady Bunch was a great setup. We did not come up with the idea of the Bradys being stuck in the ’60s, but we didn’t think they were mining as much of what was happening today, making those two worlds collide in a very edgy, fun, subversive way. Betty did say to us, “Write it for kids that have never seen ‘The Brady Bunch,’ write it for fans that grew up with it, and then write it for stoners.”

You said, “Our writing style changed forever after a year in Star’s Hollow.” In what way did it change?

Amy Sherman-Palladino is a genius. We saw that on “Roseanne,” where we met her, and first saw her genius, her stocking tights, and her top hats, as well as her office desk covered in candles. I mean, every inch was candles. I don’t know how she got away with it from the fire department, but there were a lot of candles. At that time in television, you almost had to write to the lowest common denominator. If you had a reference, it had to be one that everybody knew. They were so afraid that if somebody didn’t know a reference, they would change the station. Amy threw all that out. The weirder, the crazier. I also think it coincided with the widespread adoption of phones. They could Google, “Who is Paul Anka? Who are all these crazy music groups?” So that changed our writing in that we could open our minds and say anything. Every other script, whenever we would get a note from a network or studio, saying, “I don’t know that reference,” we would say, “Gilmore Girls.”

I also liked Amy’s almost half-hour comedy style of scenes, beginning and ending with a little joke or humor. So it always felt like there was a button or a bow at the end of the scene. I also loved the way she would set up a little kernel, like we should plant a seed in one episode, like you just meet Logan in passing, and then suddenly it blew up into this whole relationship, so it’s just kind of like life. I think that’s why the show was so endearing, because you just fall for these people and you get to know them, and it’s like peeling away the layers of an onion.

Just love people for who they are. Meet them where they are. Don’t “other” people. We’re all in this together. We all have the same color heart. I’m still going to be fighting for themes like that, I think, in all my work, and people have said that’s a common denominator in all the different TV shows that we’ve written for. You can tell there’s a heart there.