Cultural specificity from a part of the world that too rarely gets spotlighted at international film festivals join the films in this dispatch, even if the trio feel so invigoratingly different. A docudrama, a thriller, and a social commentary that unfolds like a one-act play, these three works have little in common structurally even as they all remind of cultures that deserve more attention from critics and movie goers. Sadly, only one of them truly works, a surprising truth given that the other two were directed by filmmakers who have succeeded in similar waters before.

The best of the three is a movie that wasn’t on many radars before Venice but became a must-see at TIFF after it emotionally devastated Italian audiences. Kaouther Ben Hania’s “Four Daughters” was a breakthrough for the Tunisian filmmaker, earning her an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary Feature. She uses her skills with non-fiction filmmaking to emotional effect with the crushing “The Voice of Hind Rajab,” a recounting of the events of January 29, 2024, much of which played out on social media. The world listened as a six-year-old named Hind Rajab called into the Red Crescent rescue center in Gaza to report that her entire family had been murdered by Israeli soldiers. As she lay in her car on the bodies of her aunt, uncle, and four cousins, she begged for rescuers to come, turning into a symbol for the human cost of the unfolding genocide. Red Crescent responders were forced to wait until the region was clear enough to save Hind Rajab, their frustration growing with each cry of “Save me.”

Ben Hania makes the daring choice to use Hind Rajab’s actual voice recording in the film, never leaving the Red Crescent center. A significantly worse and more exploitative version of this film casts someone as Hind Rajab and shoots footage on the scene of the murders. By keeping the audience with performers playing the frazzled people on the other end of the line, she not only avoids any sort of arguments over interpretation, she puts us in the shoes of people who feel increasingly helpless against acts of horror.

She goes a step further, even including video footage of the responders overlaid on phones in key scenes. It’s a little hard to explain, but footage of people speaking to Hind Rajab that was recorded on smartphones will often be held up over the actor playing that person. Ben Hania’s camera “films” the actual footage being filmed with her performer blurred in the background. It’s a daring choice that furthers her efforts to include as much historical veracity as possible. So much of what’s going down in that region has been warped and interpreted. Ben Hania’s greatest accomplishment may be in how she diffuses any of that by artistically presenting this tragic event.

Questions will circle around the film’s release. How is “The Voice of Hind Rajab” better than a documentary on the same subject? Well, the truth is that people don’t see non-fiction films as much as they do historical recreations. And amplification of her voice is the clear goal here. Second, is it exploitation to use the voice of a murdered girl? Her mother clearly consented as footage of her is included, and much of the audio here was released before the film was in production, making it a use of available material more than anything else. I’m always a little conflicted when a tragedy involving a child is used in filmmaking, but I also believe that true action sometimes requires being confronted with visions of true horror instead of just reading or hearing about them. “The Voice of Hind Rajab” is the confrontation its victim deserves.

Far less effective is the deeply frustrating “Unidentified,” the latest thriller from Haifaa al-Mansour, who directed the wonderful “Wadja”. As specific and fascinating as that drama was in 2012, this film is depressingly flat and generic, a movie that never digs below the surface for the majority of its runtime before taking a hard right into a ridiculously unearned twist ending that makes the boredom that preceded it feel even more insulting.

Nawal (Mila Alzahrani) is a receptionist in Riyadh, someone who makes copies for her male counterparts and watches a fascinating video stream all the time, one that blends makeup tips and true crime stories. (I actually would have preferred just watching that for 100 minutes.) When a young woman with no identification on her body is found in the desert, Nawal gets sucked into the case, first investigating on her own before basically getting approval from the police chief to get to the bottom of it. The thinking is that Nawal can get closer to the girls who knew the victim, finding out things that her male superiors couldn’t or wouldn’t care to anyway. Feminist themes bubble under the surface of “Unidentified” but too few of them gain any traction through character work or even production design, making it all feel like talking points instead of writing that’s actually interested in humanity or gender bias.

A thriller that uses social issues as mere window dressing would be one thing but “Unidentified” becomes something far more insulting in its final scenes, turning everything that came before it on its head. Al Mansour has spent much of the last decade making TV thrillers like “The Sinner” and “City on Fire,” and I’m afraid it shows with this movie’s dull visual language and insincere plotting.

Another disappointment comes from the often-great Claire Denis, although “The Fence” has just enough going on to justify a look for completists of the filmmaker behind masterpieces like “Beau Travail,” “Trouble Every Day,” and “35 Shots of Rum.” In this case, she adapts Bernard-Marie Koltes’ play Black Battles with Dogs, and there’s a sense that something gets lost through the translation of French playwright’s impression of African culture being filtered through a French filmmaker and into characters played by Brits and Americans. The dialogue has a stunted rhythm that makes it sound more like theater, which is a perfectly fine choice but drains a piece that feels like it reaches for veracity into something more shapeless. Strong performances help give it a bit of form, but it doesn’t help that it also feels like a project with themes Denis has better explored in other projects.

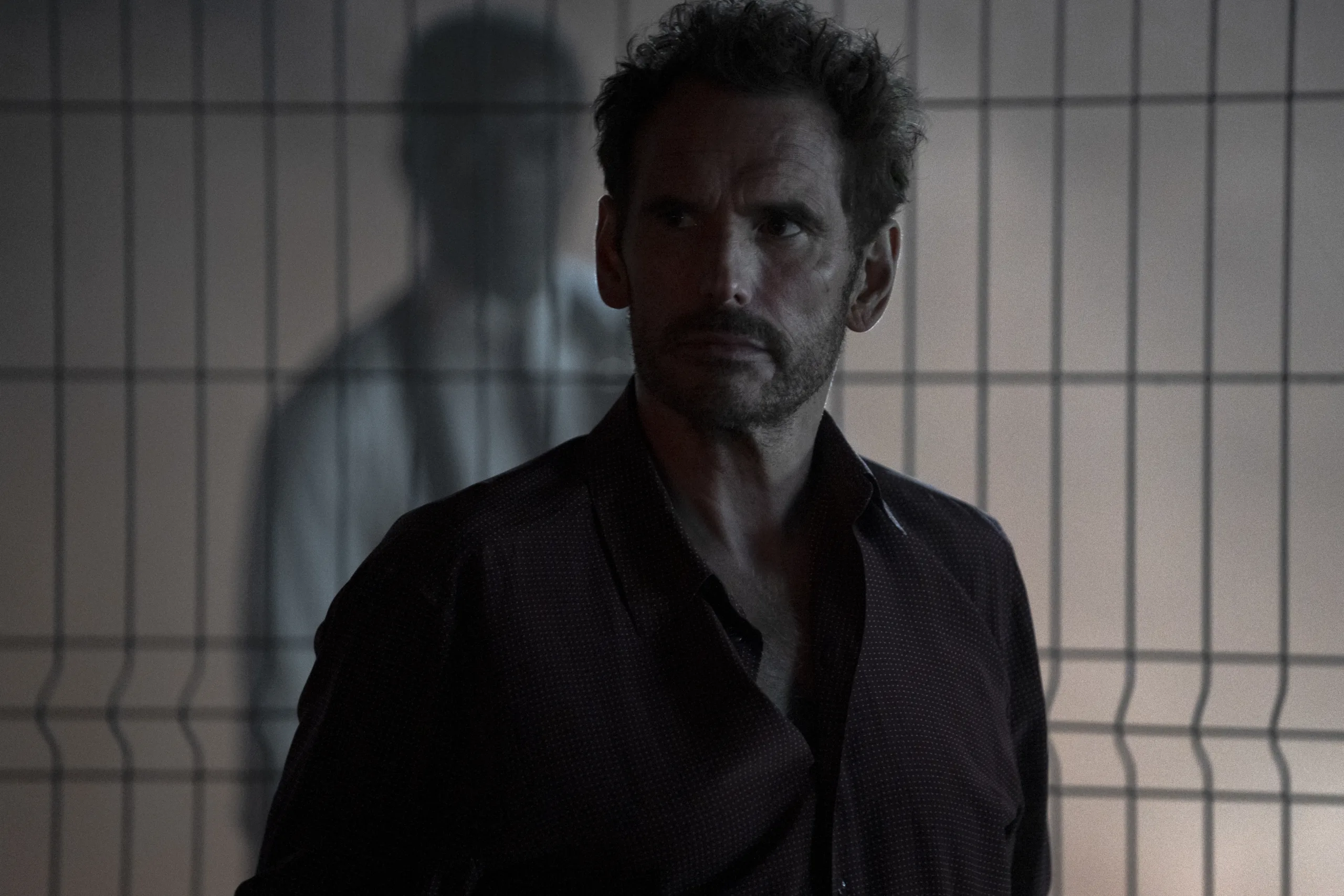

Matt Dillon plays Horn, the supervisor of a fenced construction site in Africa who is confronted by a man on the other side who is demanding the body of his brother. A local villager, Alboury (Isaach De Bankolé) insists that the deceased is turned over immediately, even as Horn tries to talk his way out of doing so in every manner possible. He offers money, he promises to deliver the body tomorrow, etc. No, it has to happen now, even though this exchange will happen in front of Horn’s arriving wife Leonie (Mia McKenna-Bruce). Meanwhile, Tom Blyth’s co-worker Cal, who clearly knows a thing or two about the “accident,” prowls the grounds behind Horn, awaiting what feels like an inevitable reckoning.

“The Fence” is basically a four-character piece and the quartet given the roles are all effective. Dillon conveys rising inadequacy at the challenge placed in front of him while Blyth represents a different form of foreign invader, the one who sings Midnight Oil’s “Beds Are Burning” in his introduction without considering that he’s a fire-starter himself. These are both shallow, impotent men yet they are given power by virtue of money and control. The problem is that “The Fence” doesn’t have much more to offer after it lays bare its themes very early in the drama. It then mostly meanders to its conclusion, lacking urgency, tension, or momentum. It’s ultimately a curiosity in the legacy of a great director’s career more than a new link in her chain.