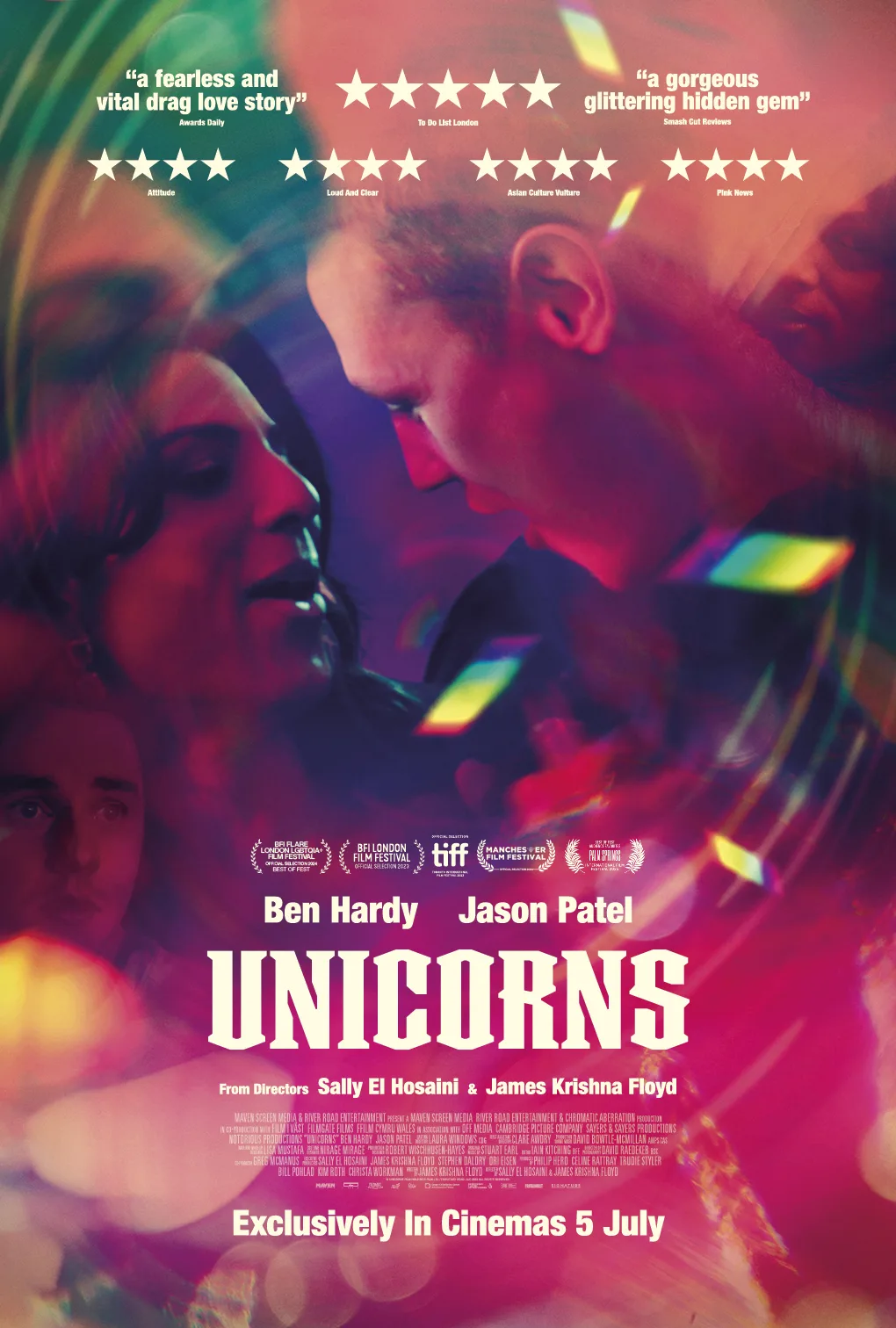

“Unicorns,” directed by Sally El Hosaini and James Krishna Floyd, doesn’t reinvent the romance genre. Still, it overcomes any rote storytelling by gifting viewers fully fleshed-out and realized characters who color between—and sometimes outside—the lines of their archetypes. A love story about a mechanic, Luke (Ben Hardy) who falls for a drag queen, Aysha (Jason Patel), the film is a grubby and prismatic tale that isn’t afraid to dive into the nuances of a cross cultural and queer romance, while also celebrating the intrinsic beauty of witnessing two people shatter the shackles of self-loathing and learn to accept themselves. It’s hard to escape from the cycles of suppression we often find ourselves in, and “Unicorns” reminds that the ability to transform and cross borders, whether physical, mental, or spiritual, is always proximate, oppressive systems, antiquated thinking, and insecurity be damned.

The film opens with Hardy’s Luke hooking up with a stranger in an unkempt field somewhere in Essex. Far from passionate and deprived of the thrill that Luke thinks such an encounter would bring, the sex is over nearly as soon as it began. Still feeling an emotional void, he takes a serendipitous wrong turn into an Indian restaurant where he’s thrust into the center of Essex’s Gaysian night club scene. As he stiffly makes his way across the chamber of contorting bodies–Hardy’s body language is earnestly awkward here, as Luke’s attempts to make himself smaller sticks out with the people on the floor who dance with abandon–his eyes are drawn to one of the stars of the club, Aysha, who is in the throes of her routine.

Their meet-cute moment is where El Hosaini and Krishna Floyd are in full collaborative sync with cinematographer David Raedeker, production designer Robert Wischhusen-Hayes, and Chris Evans-Wilson in how they capture just how seismic this meeting is. Up until Luke’s foray to the secret club, his world was one of dismal grays; cloudy skies, engine grease, and tar were the earthy, monochromatic elements that made up his world, where rigidity reigned supreme and the only emotions allowed were anger and contentment.

Aysha’s arrival at the center of the club’s stage comes with a cornucopia of strobe lights, neon signage, and glitter; it’s as intoxicating as it is vivacious, and it quite literally represents an invasion of new light into Luke’s world. It feels like a blossoming of something new. Hardy, to his credit, plays into the visual juxtaposition well, portraying Luke as someone who it feels like has never given himself to move his body in a way that wasn’t functional or for his work, let alone ever considered what the the disarming power of witnessing a curvaceous body in a glistening dress can do for the psyche and soul.

Later that same evening, Aysha and Luke hook up, but once Luke realizes that Aysha is not a cis woman, he rebuffs her. Not batting an eye, Aysha replies, “First time you kissed someone like me?” before immediately following up with “Hate that you liked it?” That assurance is something that Luke can’t easily shake despite his attempts to distance himself from his undeniable attraction. After a couple of nights, Aysha, who can’t drive, finds Luke at his workplace and asks him to be his driver. He surrenders to her proposition, and as the two drive around Essex to various shows, they grow closer to each other while also unearthing latent fears about themselves that they thought they could keep hidden.

In most stories like this, there’s a worry that Patel’s Aysha becomes a character who is relegated to the sidelines and whose agency and depth are sacrificed so the white protagonist can learn something about themselves. Thankfully, “Unicorns” sidesteps this trope; it may open on Luke, but it shifts narrative focus frequently, opting instead to showcase a rich inner and personal life of both characters without one having to come at the cost of the other. That dedication to interiority may mean there’s not as much room for novelty within the narrative, but that’s easy to forgive when Aysha and Luke are as charming as they are.

Hardy delivers career-best work here, all fixed muscle on the outside, but upon closer look, that frame acts as a cage for his more tender self that desperately wants out. So much is communicated with just an aversion of his eyes or a crossing of his arms that points to the inner cyclone of questions he’s plagued with. He struggles to hold his definition of what it means to be a good man, what it means to be a present father to his son, Jamie (Taylor Sullivan), while also honoring his own desires. Throughout the film, he unlearns in real time the stigmas and prejudices around desire and masculinity that have been so thoroughly ingrained, and it’s Hardy’s ever inquisitive eyes that make it a gift to be on this journey of self-discovery with him.

Likewise, although Patel starts as the more ostentatious of the two, he also plays Aysha’s more minor key feelings with as much conviction. When Aysha goes back home to see her family, she removes the make-up and colorful fits and goes by the straight-presenting Ashiq. Like Luke, Aysha contains multitudes, but also wrestles with whether she’ll ever be able to harmonize those peacefully. She thinks about how she can remain herself while honoring her parents’ desires. At Aysha’s home, El Hoisani and Krishan Floyd continue to use color to illuminate their characters’ emotional states. They drape Aysha in the same drab and despondent colors whenever she’s home, just like the ones Luke found himself in at the beginning of the film, signifying that whenever she’s home, she can’t quite let her full self glow.

Krishna Floyd’s script also leaves room to explore the cultural differences between Luke and Aysha, such as one poignant moment where Aysha tells Luke, “Don’t make me choose between you and my family.” For Luke, who is used to striking out on his own, he fails to understand the interpersonal dynamics of a Southeast Asian family and the consequences of what would happen if Aysha embraced a sort of toxic and uncritical individuality.

If there’s any main critique, it’s around how functional the film’s dialogue can be, although even that I found to be excusable as it embodies the awkwardness of these characters who are taking those first steps to self-actualization. There’s rarely a disconnect between what a character thinks and what they say, such as an example where Aysha tells Luke that for drag queens like her who have to keep their passion and work hidden from their disapproving families, the options are “Forced marriage abroad or jumping off a bridge.” There’s a permutation of this story where the threats speak louder because they’re implied and because we see the pain of such consequences on the faces of actors who are able to convey intrinsic fear expertly.

Ultimately, “Unicorns” is about the gift of a connection that healthily destabilizes your perceptions about yourself and the world, and makes you realize that the world is big enough to hold you in your abundance and imperfections. It’s hard not to be captivated by the ways it celebrates the grace of chance encounters and how sometimes all it takes is a little dancing and glitter to be reminded that you’re worth existing in your most authentic form.