When Andy Samberg (as Mark Zuckerberg) asked Oscar nominee Jesse Eisenberg how he played Zuckerberg in “The Social Network” (shortly before the real Zuckerberg joined them onstage during the opening monologue on “Saturday Night Live”), he said: “I speak in short, clipped sentences and I keep my head very still.”

David Bordwell has an ingenious look at The Social Network: The faces behind Facebook at Observations on film art that examines the film’s direction and performances in terms of its emphasis on facial expressions and body language.

Anybody who’s seen Eisenberg before (say, in “The Squid and the Whale” or “Adventureland“) will recognize that his Zuckerberg is indeed a stylized performance. And anybody familiar the real Mark Zuckerberg will recognize that Eisenberg’s work is not based on the actual Facebook founder, but on the character created in Aaron Sorkin’s script. (In fact, Eisenberg and Zuckerberg had never met until Saturday. Watch how eager for approval Zuckerberg is, smiling and repeatedly turning to the audience in expectation of laughs during his backstage bit with Lorne Michaels. That is not something the movie character would ever do.)

“There is no art, Hamlet says, to read the mind’s construction in the face,” Bordwell writes. “He’s right about the reading part; we grasp expressions fast, intuitively, and often reliably. But there is art in the performer’s construction of the face, and of the director’s cinematic shaping of it.”

DB’s take fits nicely with my own view of “The Social Network” (one of many) as a movie about communicating in code — for what are facial expressions and body language but some of the oldest social codes we have?

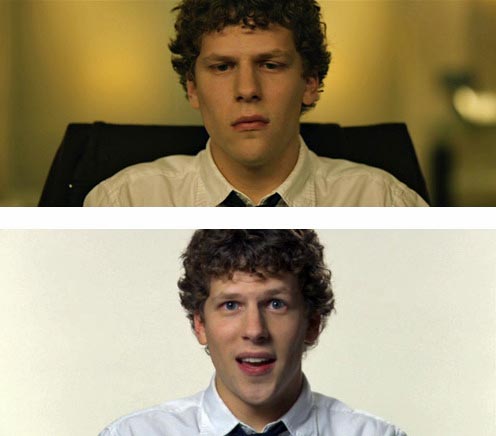

By cropping images of the actors’ eyes, eyes and eyebrows, and entire faces, DB reveals how the actors reveal their characters:

Obvious as it seems, by isolating the eyes we can notice the division of labor among eyes, eyelids, brows, and mouth: Each component supplies a bit of information. We’re remarkably skillful in integrating all these cues. What researchers into face perception call the informational triangle-the two eye regions tapering down to the mouth-creates a package of social and psychological signals. It’s this whole ensemble, the most informative parts of the face working together, that guides us in making sense of other people, or of film acting.

Take the rapid-fire opening scene, for example:

This scene introduces us to Mark’s facial behavior. He will glance to the side when he’s pressed, but he’ll focus sharply on the other person when he’s trying to dominate the conversation. His mouth seems to be dominated by the triangularis and mentalis muscles, creating the inverted smile sometimes called the “facial shrug,” even when the lips are relaxed. Erica smiles a lot, something that usually triggers a responding smile. But not from this guy, though a smirk will occasionally flit over his mouth when he says something insulting. The closest we get to a true smile, I think, is at the blowout conclusion of the contest for internships, and that’s seen in the fairly distant long shot at the top of this section.

Above those eyes and that mouth sit those hooded brows, almost never lifting or lowering. Which is to say that Mark seldom shows surprise, and his anger will usually be visible in the set of his mouth (and in his words.) His flatlined brows sometimes suggest keen concentration, sometimes aloofness when he tilts his head back, or more pervasively the sense that everything in the vicinity is irritating. He seems to be permanently scowling, an effect that Fincher and DP Jeff Cronenweth accentuate by lighting that draws his brows closer together and hollows out the eye sockets. […]

In one section of the making-of, Jesse reports that Fincher was often telling him, “Less with the eyebrows,” and onscreen Eisenberg delivered. By the end, for the last shots of Mark alone, Fincher asked for what’s become famous as the “Queen Christina” effect-an expression that could be read in many ways. “I want everybody to put anything on it.”

The result is a portrait of Generation Whatever, or an image of stoic loneliness, or of bemused curiosity about an old girlfriend, or….

One more consequence of my noting the obvious: The centrality of faces to modern movies. Today’s films use close-ups very heavily, probably more than at any other point in film history. (The Way Hollywood Tells It explores some reasons why.) What I’ve called the “intensified continuity” style of modern cinema relies on tight single shots of individual players. So modern players must be maestros of their facial muscles and eye movements. In other styles of filmmaking, currently and historically, the actor’s performance is projected onto more body parts through gestures, stance, gait, and the like. Recall Cary Grant, who performed with his whole body. Of course he wasn’t bad in close-ups either.

Faces aren’t everything in movies like The Social Network. Most characters use their arms and hands freely-probably the Winklevi the most. Mark is straightjacketed, but even he will gesture sometimes, as when a drooping Twizzler becomes his hand prop. He usually prefers a shrug, though it’s executed without the eyebrow lift most people add. Postures and personal walking styles play key roles in the film as well.

Don’t miss the whole piece, with many frame grabs, here.