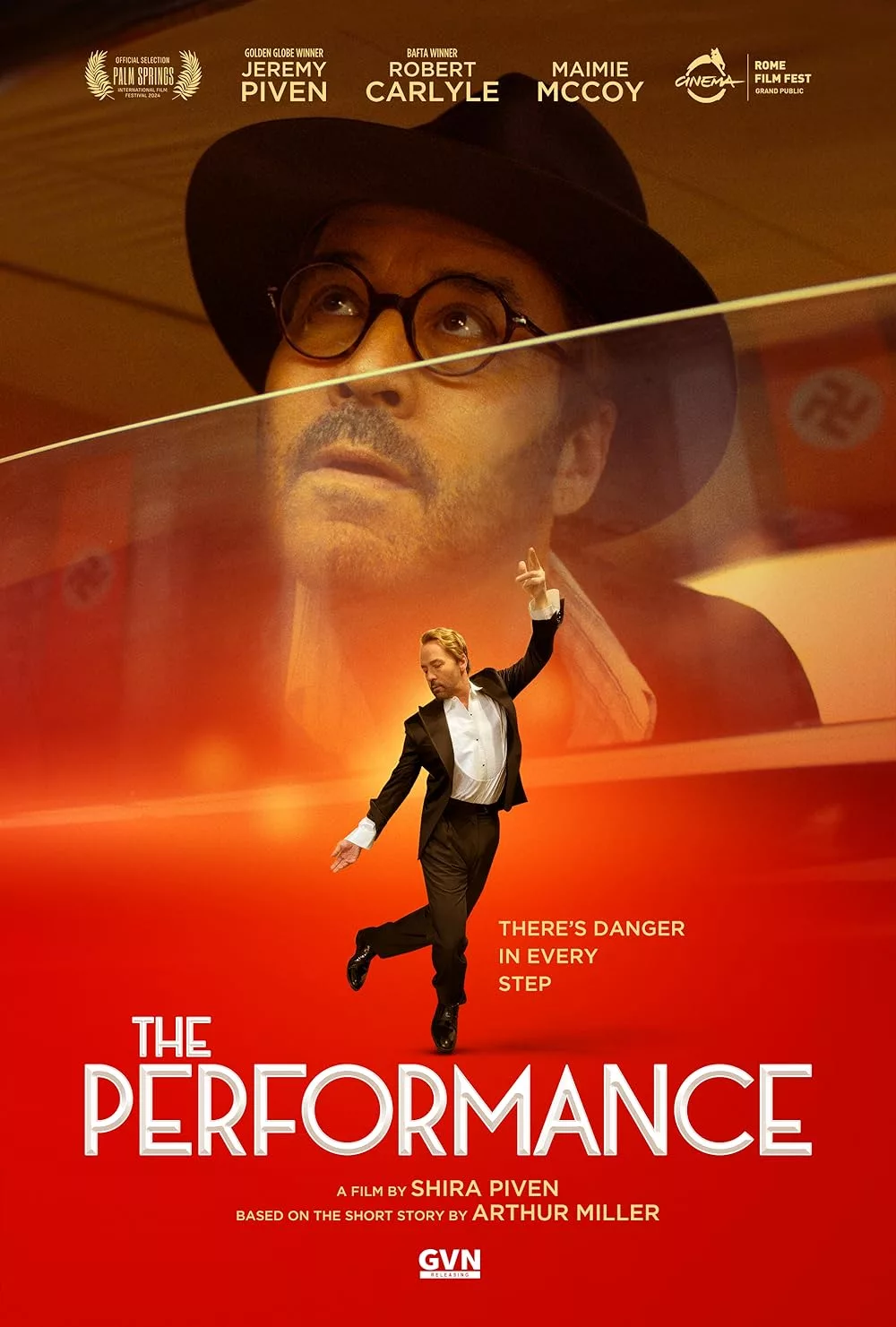

It took 15 years for the Piven siblings, director/co-screenwriter Shira Piven and producer/star Jeremy Piven, to produce “The Performance,” based on a short story by playwright Arthur Miller (Death of a Salesman, All My Sons). It was shared with the Pivens by their mother, writer, actress, and theater coach Joyce Hiller Piven. It is the story of four struggling American dancers in the late 1930s who get an offer that is both dream and nightmare—a lucrative offer to perform in a luxurious Berlin club as the Nazis are taking over Europe. Jeremy Piven plays Harold May, the leader of the dance troupe. He has said in interviews that one advantage of the 15 years of trying to get the film made was 15 years of tap-dancing lessons. They paid off; his dancing in this film is not only technically impressive but a core part of his performance, one of his all-time best. (You can catch a glimpse of choreographer Jared Grimes as a street dancer.)

We first see Harold alone in his apartment. It is dingy but with glimpses of a smoother past, clippings from a performing career that once seemed promising. But in the late 1930s, vaudeville and other venues for live performance have all but disappeared due to movies, radio, and the Depression. Harold dances, less to practice for his performance than to feel the sense of life and his identity that dance has given him since he was eight years old.

Then it is showtime, at a dowdy (but improbably for its era, integrated) club. We meet the members of his troupe. The two men are where they are usually found just before going on stage. Paul (Isaac Gryn) is panicking with stage fright in the bathroom. Benny (the brilliant dancer Adam Garcia) is having sex. The sole woman of the group is about to be injured by a board on the stage that is not nailed down. She will be replaced for the European tour by Carol (Maimie McCoy), whose devil-may-care demeanor does not conceal how desperate she is for money. She also has a complicated past with Harold.

After a series of performances in small clubs, Damian Fugler (Robert Carlyle) comes to Harold’s dressing room to make him an offer, a gigantic payment plus expenses for just one night in Berlin. The money and the glamour are too much to resist, and it’s just for one night. We can see some concerning details (watch the club manager), but the dancers are dazzled by the fabulous hotel, with Harold in the suite the King of Prussia says is better than his castle. We can believe it. Then, the audience at the club is all escorted out. From backstage, with Harold watching behind mottled red glass, the dancers see that their audience will be Hitler and his top officers.

Miller, who spent his career in the world of the theater and wrote a movie for his then-wife Marilyn Monroe, had a deep understanding of performers, why and how they are willing to go to almost any extreme to be in front of an appreciative audience. This adds a welcome depth to the story and its moral quandaries. It is not just that Harold wants appreciation or fame or luxurious surroundings. He feels he is owed this form of stardom, something that was taken from him by circumstance, not lack of talent or effort.

The production design by Vlad Vieru and cinematography by Lael Utnik are exceptional, with striking and dynamic visuals that add interest and provide context. Characters seated at a dining table in a hunting lodge face a trophy wall of antlered deer heads. Shira Piven uses one character’s use of a home movie camera to give us some “amateur” footage through his eyes. Editors Oona Flaherty, Jessica Hernández, and Michael Hofacre, making the most of the percussive tap steps, graceful gestures, and buoyant showmanship. And a scene where Harold is being examined by a doctor is almost unbearably suspenseful. Harold can hide his Jewishness with his boxers on, but the doctor insists on removing them.

This film is not intended to be historically accurate. The Nazis were not fans of jazz or any music connected to non-Aryans. In this version of late 1930s Berlin, Hitler is so enthusiastic that he insists on another performance, one that will require Harold to train local dancers for a production number. Will he stay, or will he go? Can he go? Has he stayed too long, become too entangled?

The title has several layers of meaning. The central conflict of the storyline is an invitation to perform for Hitler. But the movie makes clear that Harold’s entire life has been a performance. He changed his last name to seem more “American,” meaning not the son of Jewish immigrants. In New York, passing as gentile simply meant access to certain jobs and residences. (He mentions that he has never been to Connecticut, which in those days had restrictive covenants in some areas prohibiting sales of homes to African Americans and Jews.) In Nazi Germany, ability to pass is about to become a matter of life or death. The troupe’s performances themselves are about more than the dancing. The men appear in spotless white tie. The act is as much about aspirational elegance and sophistication as it is about skill. Later, Harold has another kind of performance, a statement he chooses to make in public.

The Pivens, who literally grew up together and made this as a passion project, have a shared vision, and a level of comfort and communication that brings sincerity and authenticity to the performances at every level.