Pauline Kael.

"I love subtextual film criticism, especially when it's fun, when a guy knows how to write in a readable, charming way. What I love the most about it is that it doesn't have a f---ing thing to do with what the writer or the actor or the filmmakers intended. It just has to work. And if you can make your case with as few exceptions as possible, then that's great." -- Quentin Tarantino, in Sight & Sound, February, 2008

Quentin Tarantino is a big fan of Pauline Kael, who may have encouraged more people to articulate their love for movies than anyone of her generation. She wasn't necessarily all that big on what he calls "subtextual film criticism," but she knew how to write in a readable, engaging and idiosyncratic style. The titles of her collections of reviews and essays, with their suggestive sexual and romantic overtones -- "I Lost It at the Movies," "Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang," "Deeper Into Movies," "Reeling," "When the Lights Go Down" -- told you everything about her approach to movies. I don't remember her using the word "film" or "cinema" much, unless it was to deride them as vacuous or pretentious. Though she became most famous and influential while writing for an upper-caste, urban(e) institution, The New Yorker, that reeked of calcified East Coast provincialism, she presented herself as an ardent movie populist. (Kael came from the northern coast of California.)

In November, 1964 -- that would be about 43 years ago, for those keeping count -- she published an essay for The Atlantic Monthly called, "Are Movies Going to Pieces?" in which she asks a lot of questions we're still asking today (see recent Scanners post and discussion, "Moviegoers who feel too much," and Stephen Whitty's column in last Sunday's Newark Times-Ledger," Critic's Choice").

"If I say I am a film critic, you will agree."

Standard disclaimer-cliché: I obviously don't concur with all that Kael says here (but at least at this point in her career she was willing to admit to feeling some ambivalence!). One of the things I've always found fascinating about her is that, even when I believe she's dead wrong, she unwittingly includes much of the evidence to make a case against her right there in her review. It's not that she didn't observe what was there, but that she drew such different conclusions from it. Also, her favorite rhetorical trick is the false dichotomy. It's fun to consider her arguments, but are we really forced to make such dramatic (or simplistic) either/or choices: "The Eclipse" or "His Girl Friday"? "Art" or entertainment? Right brain or left brain? Herman J. Mankiewicz or Orson Welles? George W. Bush or Osama bin Laden?

"Are Movies Going to Pieces?" (1964). Most of these excerpts are from the middle and the very end:

I trust I won't be mistaken for the sort of boob who attacks ambiguity or complexity. I am interested in the change from the period when the meaning of art and form in art was in making complex experience simple and lucid, as is still the case in "Knife in the Water" [Roman Polanski, 1962] or "Bandits of Orgosolo" [Vittorio De Seta, 1960], to the current acceptance of art as technique, the technique which in a movie like "This Sporting Life" [Lindsay Anderson, 1963] makes a simple, though psychologically confused, story look complex, and modern because inexplicable.

It has become easy—especially for those who consider "time" a problem and a great theme—to believe that fast editing, out of normal sequence, which makes it difficult, or impossible, for the audience to know if any action is taking place, is somehow more "cinematic" than a consecutively told story. For a half century movies have, when necessary, shifted action in time and place and the directors generally didn't think it necessary to slap us in the face with each cut or to call out, "Look what I can do!" [...]

In one way or another, almost all the enthusiasts for a film like ["This Sporting Life"] will tell you that it doesn't matter, that however you interpret the film, you will be right... Surely [they] can read the most onto a blank screen?

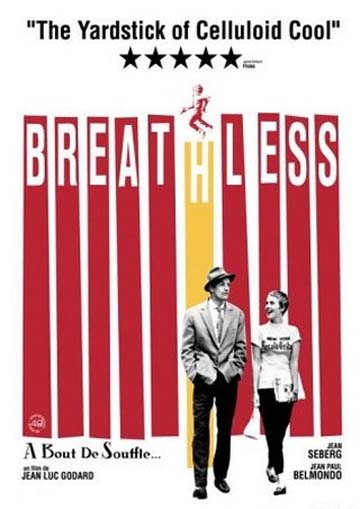

UK DVD cover.

Kael herself often demonstrated that criticism is autobiography -- and her assumption that people emerging from a movie should instantly, instinctively and definitively know "whether they liked it" is a perfect example of that. Her reviews, like anyone's, are a chronicle of who she was and the time in which she wrote and whatever she was thinking about at the time. You can see this all the more clearly in the chronologically arranged collections. Kael claimed never to see a movie twice, and to always know exactly how she "felt" about each one -- something that seems preposterous, and probably disingenuous, to someone like me, for whom a couple hours in the presence of a movie is so often an experience I can't so easily or readily process. (I've always asked publicists not to probe me for my opinions as I'm leaving a screening -- but if I love it or hate it right then I may volunteer a response on my own.)There's not much to be said for this theory except that it's mighty democratic. Rather pathetically, those who accept this Rorschach-blot approach to movies are hesitant and uneasy about offering reactions. They should be reassured by the belief that whatever they say is right, but as it refers not to the film but to them (turning criticism into autobiography) they are afraid of self-exposure. I don't think they really believe the theory—it's a sort of temporary public convenience station. More and more people come out of a movie and can't tell you what they've seen, or even whether they liked it. [...]

... Although "L'Avventura" is a great film, had I been present at Cannes in 1960, where Antonioni distributed his explanatory statement, beginning, "There exists in the world today a very serious break between science on the one hand...," I might easily have joined in the hisses, which he didn't really deserve until the following year, when "La Notte" revealed that he'd begun to believe his own explanations—thus making liars of us all.

When we see Dwight Macdonald's cultural solution applied to film, when we see the prospect that movies will become a product for "Masscult" consumption, while the "few who care" will have their High Culture cinema, who wants to take the high road? There is more energy, more originality, more excitement, more art in American kitsch like "Gunga Din," "Easy Living," the Rogers and Astaire pictures like "Swing Time" and "Top Hat," in "Strangers on a Train," "His Girl Friday," "The Crimson Pirate," "Citizen Kane," "The Lady Eve," "To Have and Have Not," "The African Queen," "Singin' in the Rain," "The Sweet Smell of Success," or more recently, "The Hustler," "Lolita," "The Manchurian Candidate," "Hud," "Charade," than in the presumed "High Culture" of "Hiroshima, Mon Amour," "[Last Year at] Marienbad," "La Notte," "The Eclipse," and the Torre Nilsson pictures. As Nabokov remarked, "Nothing is more exhilarating than Philistine vulgarity."

Regrettably, one of the surest signs of the Philistine is his reverence for the superior tastes of those who put him down. Macdonald believes that "a work of High Culture, however inept, is an expression of feelings, ideas, tastes, visions that are idiosyncratic and the audience similarly responds to them as individuals." No. The "pure" cinema enthusiast who doesn't react to a film but feels he should, and so goes back to it over and over, is not responding as an individual but as a compulsive good pupil determined to appreciate what his cultural superiors say is "art." Movies are on their way into academia¹ when they're turned into a matter of duty: a mistake in judgment isn't fatal, but too much anxiety about judgment is. In this country, respect for High Culture is becoming a ritual.

If debased art is kitsch, perhaps kitsch may be redeemed by honest vulgarity, may become art. Our best work transforms kitsch, makes art out of it; that is the peculiar greatness and strength of American movies, as Godard in "Breathless" and Truffaut in "Shoot the Piano Player" recognize. Huston's "The Maltese Falcon" is a classic example. [...]

The Black Bird (center).

In the last few years there has appeared a new kind of filmgoer: he isn't interested in movies but in cinema.... [A] doctor friend called me after he'd seen "The Pink Panther" to tell me I needn't "bother" with that one, it was just slapstick. When I told him I'd already seen it and had a good time at it, he was irritated; he informed me that a movie should be more than a waste of time, it should be an exercise of taste that will enrich your life. Those looking for importance are too often contemptuous of the crude vitality of American films, though this crudity is not always offensive, and may represent the only way that energy and talent and inventiveness can find an outlet, can break through the planned standardization of mass entertainment. [Aside from JE: And Kael claimed she wasn't an aueterist?!?!] [...]

... Many academics have always been puzzled that [James] Agee could care so much about movies. [Lawrence] Alloway,¹ by taking the position that Agee's caring was a maladjustment, re-established their safe, serene worlds in which if a man gets excited about an idea or an issue, they know there's something the matter with him.

Kael also comes across here as virulently anti-academic here -- but, I confess, I know nothing about the status of film in American academia in 1964. Sure, the rigid politics and conventions of academia have helped to stunt and stifle a lot of good minds, and ruin potentially good writers by turning them into automatons who learn to write for at other academics, for publication (aka, job security). But that's surely an individual flaw as much as an institutional one. Thinking rigorously and analytically (like an "academic") does not necessarily mean succumbing to obscurantism and humorlessness. Not every intellec-shul feels the need to theorize about how many angels can dance on the head of Apichatpong Weerasethakul. But even if some analyses of Weerasethakul's films are dead and empty, that doesn't mean the films themselves are.

Kael tears apart movies like David Lean's 1957 "The Bridge on the River Kwai" for being sloppy and incoherent: "Was it possible that audiences no longer cared if a film was so untidily put together that information crucial to the plot or characterizations was obscure or omitted altogether?" Yet she adores Howard Hawks' 1946 "The Big Sleep" -- a movie that, famously, even those who made it never bothered to quite figure out. Audiences, Kael writes, used to insist that the movie get the story straight: "A movie had to tell some kind of story that held together: a plot had to parse." Well, not always. Kael never saw the unearthed original cut of "The Big Sleep" -- without the most memorable Bogart-Bacall scenes that didn't do much to advance the plot -- in which the story was explained, but nobody really cared.

Reading Kael's piece now, I find it interesting what a difference four-plus decades (and a two-term presidency) can make. Given what I see as a prevailing anti-intellectualism in American culture today (the highest standard of evaluation is whether you feel like you could have a beer with it), I wonder if anyone besides A-- C------ would write a sentence like: "In this country, respect for High Culture is becoming a ritual."

What do you see in Kael's piece that matters to you -- or doesn't? Any points you'd like to expand upon? C'mon: Do you like it or not?

- - - -

¹ Kael makes a reference to "Critics in the Dark," an essay by Lawrence Alloway published in the "prestigious" Encounter, which she says appealed to "several of the academic people I know who have least understanding of movies." I found an excerpt online:

There is a new problem facing critics who are now starting to approach pop movies seriously, which arises from their dependence on the idea of individual authorship. Detailed analysis of the work of pop directors who work within the commercial framework has certainly revealed some recurring factors which are, correctly, translatable into a personal style. However, such nuanced discrimination risks being more like the esoteric expertise of specialists than like the humanist's tribute to individuality. [...] The risk for film criticism is that the canon of individual authorship, applied to an expendable art form, will simply lead to the insulation of criticism within a kind of hobbies-corner specialism. Then the criticism of pop films might become technical and esoteric, like the cult of Hi Fi, or like surfing in the United States. In point of fact, what is needed is a criticism of movies as a pop art which can have a critical currency beyond that of footnotes and preposterous learning."

(tip: thepopview in a girish comment.)