There is no movie musical more fun than “Singin’ in the Rain,” and few that remain as fresh over the years. Its originality is all the more startling if you reflect that only one of its songs was written new for the film, that the producers plundered MGM’s storage vaults for sets and props, and that the movie was originally ranked below “An American in Paris,” which won a best picture Oscar. The verdict of the years knows better than Oscar: “Singin’ in the Rain” is a transcendent experience, and no one who loves movies can afford to miss it.

The film is above all lighthearted and happy. The three stars–Gene Kelly, Donald O'Connor and 19-year-old Debbie Reynolds–must have rehearsed endlessly for their dance numbers, which involve alarming acrobatics, but in performance they’re giddy with joy. Kelly’s soaking-wet “Singin’ in the Rain” dance number is “the single most memorable dance number on film,” Peter Wollen wrote in a British Film Institute monograph. I’d call it a tie with Donald O’Connor’s breathtaking “Make ’em Laugh” number, in which he manhandles himself like a cartoon character.

Kelly and O’Connor were established stars when the film was made in 1952. Debbie Reynolds was a newcomer with five previous smaller roles, and this was her big break. She has to keep up with two veteran hoofers, and does; note the determination on her pert little face as she takes giant strides when they all march toward a couch in the “Good Morning” number.

“Singin’ in the Rain” pulses with life; in a movie about making movies, you can sense the joy they had making this one. It was co-directed by Stanley Donen, then only 28, and Kelly, who supervised the choreography. Donen got an honorary Oscar in 1998, and stole the show by singing “Cheek to Cheek” while dancing with his statuette. He started in movies at 17, in 1941, as an assistant to Kelly, and they collaborated on “On the Town” (1949) when he was only 25. His other credits include “Funny Face” and “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers.”

One of this movie’s pleasures is that it’s really about something. Of course it’s about romance, as most musicals are, but it’s also about the film industry in a period of dangerous transition. The movie simplifies the changeover from silents to talkies, but doesn’t falsify it. Yes, cameras were housed in soundproof booths, and microphones were hidden almost in plain view. And, yes, preview audiences did laugh when they first heard the voices of some famous stars; Garbo Talks!” the ads promised, but her co-star, John Gilbert, would have been better off keeping his mouth shut. The movie opens and closes at sneak previews, has sequences on sound stages and in dubbing studios, and kids the way the studios manufactured romances between their stars.

When producer Arthur Freed and writers Betty Comdon and Adolph Green were assigned to the project at MGM, their instructions were to recycle a group of songs the studio already owned, most of them written by Freed himself, with Nacio Herb Brown. Comdon and Green noted that the songs came from the period when silent films were giving way to sound, and they decided to make a musical about the birth of the talkies. That led to the character of Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen), the blond bombshell with the voice like fingernails on a blackboard.

Hagen in fact had a perfectly acceptable voice, which everyone in Hollywood knew; maybe that helped her win an Oscar nomination for best supporting actress. (“Singin’ “ was also nominated for its score, but won neither Oscar–a slow start for a film that placed 10th on the American Film Institute list of 100 great films, and was voted the fourth greatest film of all time in the Sight & Sound poll.) She plays a caricatured dumb blond, who believes she’s in love with her leading man, Don Lockwood (Kelly), because she read it in a fan magazine. She gets some of the funniest lines (“What do they think I am? Dumb or something? Why, I make more money than Calvin Coolidge put together!”).

Kelly and O’Connor had dancing styles that were more robust and acrobatic than the grandmaster, Fred Astaire. O’Connor’s “Make ’em Laugh” number remains one of the most amazing dance sequences ever filmed — a lot of it in longer takes. He wrestles with a dummy, runs up walls and does backflips, tosses his body around like a rag doll, turns cartwheels on the floor, runs into a brick wall and a lumber plank, and crashes through a backdrop.

Kelly was the mastermind behind the final form of the “Singin’ in the Rain” number, according to Wollen’s study. The original screenplay placed it later in the film and assigned it to all three stars (who can be seen singing it together under the opening titles). Kelly snagged it for a solo and moved it up to the point right after he and young Kathy Selden (Reynolds) realize they’re falling in love. That explains the dance: He doesn’t mind getting wet, because he’s besotted with romance. Kelly liked to design dances that grew out of the props and locations at hand. He dances with the umbrella, swings from a lamppost, has one foot on the curb and the other in the gutter, and in the scene’s high point, simply jumps up and down in a rain puddle.

Other dance numbers also use real props. Kelly and O’Connor, taking elocution lessons from a voice teacher, do “Moses Supposes” while balancing on tabletops and chairs (it was the only song written specifically for the movie). “Good Morning” uses the kitchen and living areas of Lockwood’s house (ironically, a set built for a John Gilbert movie). Early in the film, Kelly climbs a trolley and leaps into Kathy’s convertible. Outtakes of the leap show Kelly missing the car on one attempt and landing in the street.

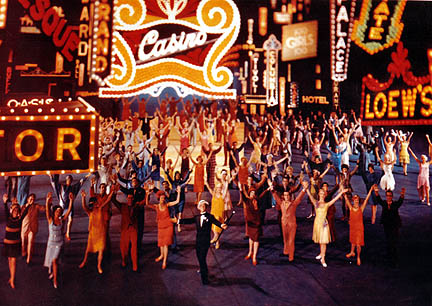

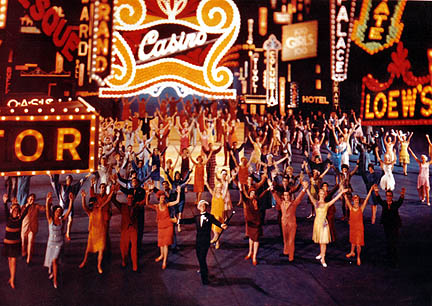

The story line is suspended at the two-thirds mark for the movie’s set piece, “Broadway Ballet,” an elaborate fantasy dance number starring Kelly and Cyd Charisse. It’s explained as a number Kelly is pitching to the studio, about a gawky kid who arrives on Broadway with a big dream (“Gotta Dance!”), and clashes with a gangster’s leggy girlfriend. MGM musicals liked to stop the show for big production numbers, but it’s possible to enjoy “Broadway Ballet” and still wonder if it’s really needed; it stops the headlong energy dead in its tracks for something more formal and considered.

The climax ingeniously uses strategies that the movie has already planted, to shoot down the dim Lina and celebrate fresh-faced Kathy. After a preview audience cheers Lina’s new film (her voice dubbed by Kathy), she’s trapped into singing onstage. Kathy reluctantly agrees to sing into a backstage mike while Lina mouths the words, and then her two friends join the studio boss in raising the curtain so the audience sees the trick. Kathy flees down the aisle–but then, in one of the great romantic moments in the movies, she’s held in foreground closeup while Lockwood, onstage, cries out, “Ladies and gentlemen, stop that girl! That girl running up the aisle! That’s the girl whose voice you heard and loved tonight! She’s the real star of the picture–Kathy Selden!” It’s corny, but it’s perfect.

The magic of “Singin’ in the Rain” lives on, but the Hollywood musical didn’t learn from its example. Instead of original, made-for-the-movies musicals like this one (and “An American in Paris,” and “The Band Wagon”), Hollywood started recycling pre-sold Broadway hits. That didn’t work, because Broadway was aiming for an older audience (many of its hits were showcases for ageless female legends). Most of the good modern musicals have drawn directly from new music, as “A Hard Day's Night,” “Saturday Night Fever” and “Pink Floyd the Wall” did. Meanwhile, “Singin’ in the Rain” remains one of the few movies to live up to its advertising. “What a glorious feeling!” the posters said. It was the simple truth.