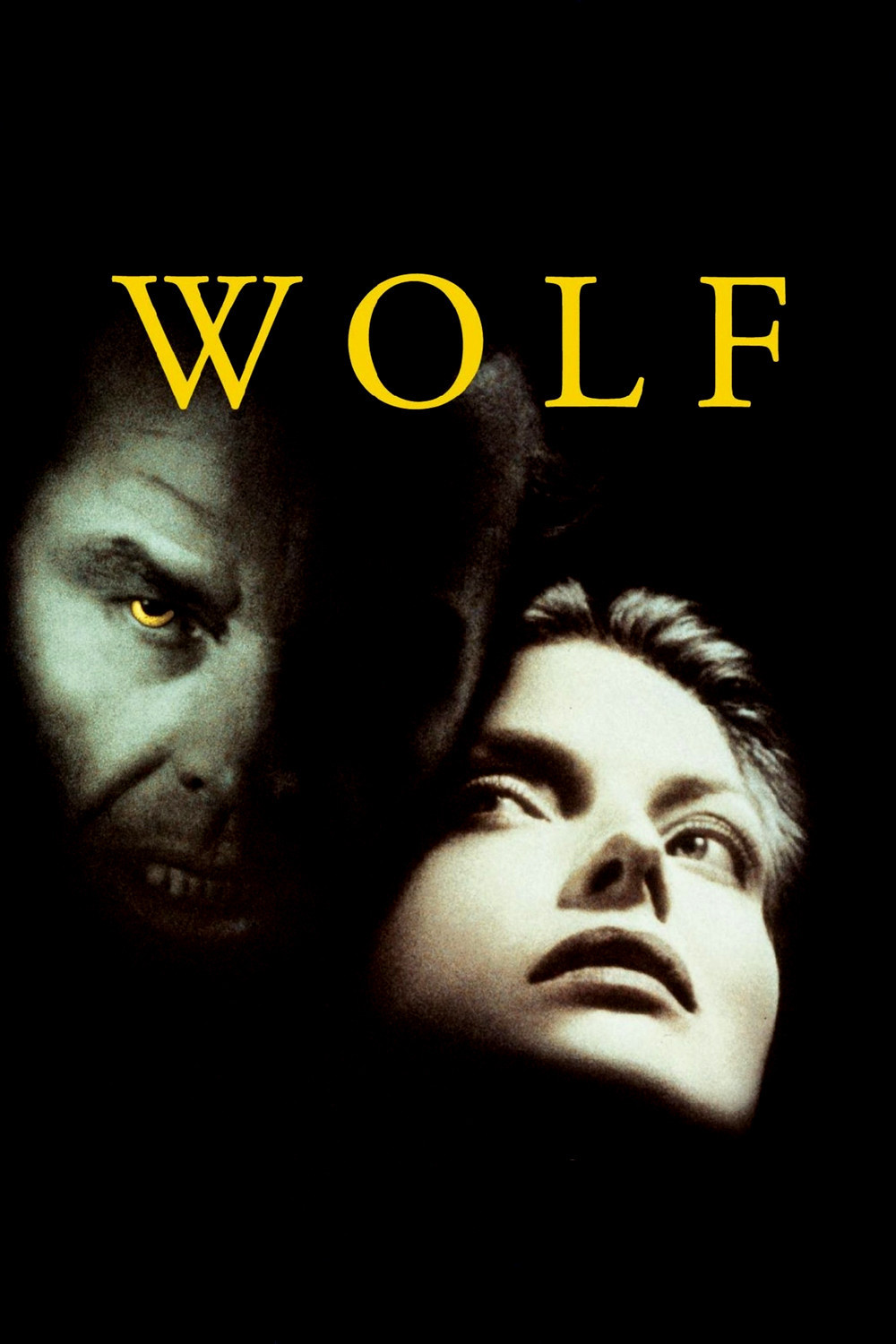

“Wolf” stars Jack Nicholson as a top editor for a New York publishing house, who is bitten by a wolf and begins to turn into a werewolf, just as a billionaire tycoon buys the company and replaces Nicholson with a back-stabbing yuppie. Nicholson, snarling with rage, bites the yuppie, who also begins to grow hair and fangs. The result is a canny portrait of the emotional climate in the New York publishing industry.

The movie contains most of the materials of traditional werewolf movies. Much significance is attached to the full moon, and horses shy away when Nicholson comes near, and his sense of smell develops to the point where he can tell that a man had tequila for his breakfast. There is of course the obligatory eccentric old scientist with the foreign accent, who explains werewolves to Nicholson. And beautiful women to be his lovers and/or victims.

But “Wolf” is both more and less than a traditional werewolf movie. Less, because it doesn’t provide the frankly vulgar thrills and excesses some audience members are going to be hoping for. And more, because Nicholson and his director, Mike Nichols, are halfway serious about exploring what might happen if a New York book editor did become a werewolf.

Nicholson looks tired and aging in the opening scenes. He’s playing Will Randall, a soft-spoken, pipe-smoking literary man of the old school, whose authors are loyal to him. Then a rich investor (Christopher Plummer) buys the firm, and throws a party during which he takes Nicholson out on the lawn to tell him he is being fired. His replacement, a traitor Nicholson thought was his friend, is the polished young hypocrite Stewart Swinton (James Spader, playing what can only be called the James Spader role, and playing it very nicely, too).

This scenario doesn’t develop as office politics as usual, however, because of the strange experience Nicholson had a few nights earlier in Vermont, where he was bitten by a wolf. Soon hair begins to flourish around the wound, and Nicholson sleeps all day but is awake all night, and his wife (Kate Nelligan) is caught in an adulterous affair because Nicholson is able to smell his rival on his wife’s clothing. Meanwhile, Laura, the millionaire’s daughter (Michelle Pfeiffer) becomes Nicholson’s confidant. Any enemy of her father’s is a friend of hers.

The tone of the movie is steadfastly smart and literate; even in the midst of his transformation, the Nicholson character is capable of sardonic asides and a certain ironic detachment. He does, however, grow more predatory.

“I’m going to get you,” he promises Spader. And after he urinates on the younger man’s shoes, he explains: “I’m marking my territory.” All of this is not quite as poignant as it might have been.

A similar movie, David Cronenberg’s “The Fly,” starred Jeff Goldblum as a scientist who realizes he is gradually becoming a fly, and Geena Davis as the woman who tries to love him in spite of . . . well, in spite of the fact that he’s a fly. There was true emotion there, and dread. Nicholson’s character, on the other hand, seems to enjoy becoming a wolf. He begins to look younger and stronger, and although he fears what he may do and sometimes demands to be locked up, there is the sense that being a wolf is not com pletely unacceptable to him. Of course (this is strictly my personal opinion), it is better to be a wolf than a fly.

The Pfeiffer character is described fairly accurately in one of Nicholson’s speeches as the kind of person who puts up a hostile exterior, but when you get past that, you find a hostile interior.

Not much of an effort is made to convince us of their romantic chemistry; they are partners mostly because they share the same enemies.

Like many Nichols movies, “Wolf” gains by surrounding the story with sharply seenplaces and details. The publishing house inhabits a classic old architectural landmark with an open atrium (ideal for a wolf who wants to eavesdrop), and other action takes place at the millionaire’s estate, with its vast lawns and forests, its Gothic main house, and its rambling outbuildings and guest cottages. The atmosphere adds to the effect; it would be difficult to stage a werewolf story in a condo.

What is a little amazing is that this movie allegedly cost $70 million. It is impossible to figure where the money all went, even given the no-doubt substantial above-the-line salaries. The special effects are efficient but not sensational, the makeup by Rick Baker is convincing but wisely limited, and the movie looks great, but that doesn’t cost a lot of money. What emerges is an effective attempt to place a werewolf story in an incongruous setting, with the closely observed details of that setting used to make the story seem more believable. Nicholson is very good with the material (some of his line readings are balancing acts of the savage and the sublime), but this material can only take him, and us, so far.