Ingmar Bergman is a great filmmaker, but in “The Serpent’s Egg” he did not make a good film, and so maybe you’ll forgive me if I begin, not on a solemn note, but on an irreverent one, with a little background from the period the film was made.

Bergman left his beloved Sweden in 1976, charging that the tax authorities were hounding him (a charge that the Swedish courts later upheld). He flew to California to meet with Dino De Laurentiis, who would eventually sign him to direct “The Serpent’s Egg.” And he became the subject of an anecdote by the great Bergman-watcher, Mel Brooks.

“When Bergman left Sweden,” Brooks said, “he complained about the persecution, the metaphysical anguish, the impossibility of realizing himself as an artist, the impotence created by the welfare state, the creeping Big Brotherism of the state … When he left California three weeks later, he complained about the heat.”

Maybe the point is that Bergman is best as a filmmaker on his native ground, no matter how unhappy he may feel there. In Sweden, during 35 years and with more than 30 films, he made only four comedies. One of them was successful (“Smiles of a Summer Night“). Two of them were passable. One was the worst film he has ever made (“All these Women”). But in his dramas — those brooding, lonely, and violent excursions into the human soul — he made some of the greatest films that ever will be made. And they all drew directly from his experiences in Sweden.

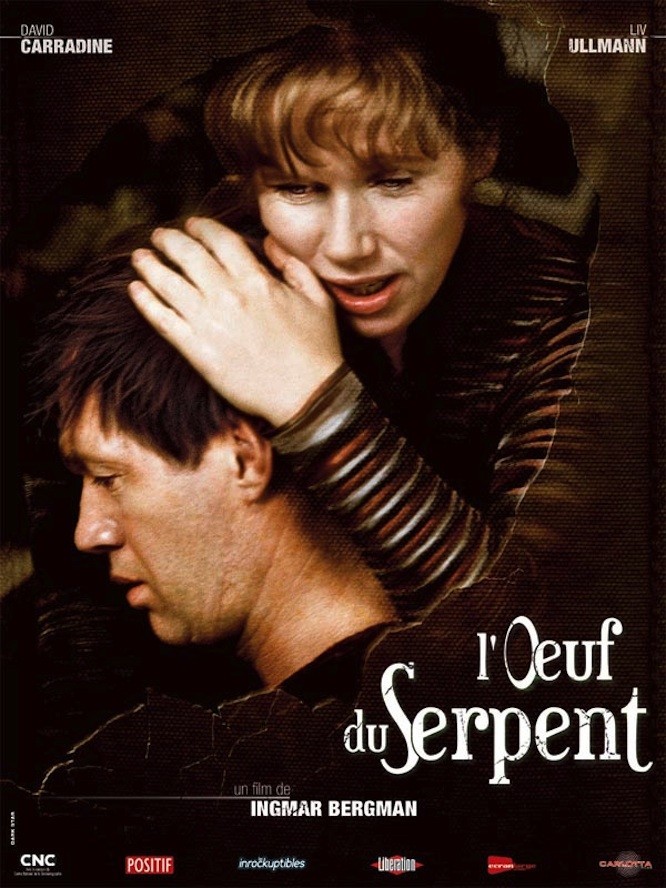

“The Serpent’s Egg” was filmed on location in West Berlin, in English, with only one performer who had worked with him before Liv Ullmann. It was set in 1923. Bergman knew the country slightly, and he knew the period through old memories (he was sent as a young boy to live awhile with a German family through an exchange program, and remembers first hand the beginnings of Nazism). But it’s clear that he did not know Germany, 1923, or Nazism well enough to make this film. It’s sad and perplexing but true: This film owes more to “Cabaret,” an American musical, than it does to whatever insights Bergman may have thought he had about his subject. The moments when the film rings true are when he returns, even unwittingly, to some of the obsessions of his Swedish films: when, for example, an American priest played by James Whitmore protests that he feels himself powerless, and we are reminded of the anguish of the ministers in “Winter Light” and “Cries and Whispers.”

For the rest, the movie is a cry of pain and protest, a loud and jarring assault, but it is not a statement and it is certainly not a whole and organic work of art. The movie attacks us, but in self-defense. There are loud, hurtful noises, shouts, and screams, self-destructive orgies and an overwhelmingly relentless decadence. But there is no form, no pattern, and when Bergman tries to impose one by artsy pseudo-newsreel footage and a solemn narration, he reminds us only of the times he has used both better.

The story concerns two people thrown together as Germany gradually stoops to embrace Hitler: David Carradine, as a touring circus performer, and Liv Ullmann, as the woman who was married to his brother (the brother blows his brains out in the film’s opening sequence). They make do as best they can, Ullmann working in a cabaret, Carradine finding work here and there and finding it uncomfortable to be Jewish.

Bergman strains for impact, giving us scenes obviously meant to be forewarnings of the Nazi genocide, the death camps, and their witch doctors. He looks emptiness in the face, and it outstares him. He hurls himself at this material, using excesses of style and content we’ve never seen from him before, but the subject defeats him. Maybe that’s what he’s admitting at the end, when the narrator remarks that the Carradine character “escaped from his police escort on the way to the train station, disappeared, and was never seen or heard from again.” A frustrating ending for a sterile film.

Bergman returned to Sweden after making this film, and found there, in the remaining years of his active career, themes he related to from the bottom of his soul. Germany was apparently as much a mystery to him as California.